In the note below, independent economist Tony Alexander argues that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has tightened interest rates too much and will be forced to slash them.

Age impact on the spending downturn

My view for a while has been that just as the Reserve Bank over-stimulated the economy during and for too long after the pandemic they have now over-restricted it.

Just as they belatedly realised their mistake and raised interest rates quickly (eventually) they are also likely later this year to belatedly realise they have tightened too much for too long and will cut interest rates relatively quickly.

Evidence to back a view that the economy is weakening more than necessary to generate the traditional lagged impact on inflation of higher interest rates has been discussed here over the past few weeks.

Examples include the fresh decline in business sentiment, although I attribute some of the pullback observed in surveys from NZIER and ANZ as the upward bias from Labour losing the election now evaporating.

GDP data confirm the economy is back in recession.

People’s spending plans measured in my monthly survey have deteriorated with a net 30% of respondents now planning cutbacks as compared with 24% in March and 13% in December.

The tone of media discussion about the economy has definitely changed in the face of widespread redundancies in the public sector.

Corporates are also catching up on restructuring they would normally have done in their multi-year cycles by now but which were delayed by the pandemic.

But businesses more generally are slimming down as cash flows pull back, the IRD takes a different attitude, and previous sources of savings have dried up.

One comment which people have put to me is that the burden of tight monetary policy is borne disproportionately by young people and older people are getting along quite well.

From a debt-servicing cash flow point of view there is validity to that argument. It’s nothing new. But that is where it ends.

Older people may be only minimally affected by higher mortgage rates but they are at greatest risk of being in middle management positions in businesses and therefore at higher risk of layoff.

These noncustomer facing/back office roles are often gutted in large numbers when overdue restructurings have to be undertaken.

The layoff risk is magnified by the nature of the rapidly changing world we live in now.

Businesses seek those able to easily incorporate the latest technologies into their work practices, research, outputs etc.

Young people know nothing other than new technologies appearing throughout their lives, stretching such technologies to their limits and beyond, and looking for the new use which may make them millions – or at least notorious online.

But even taking all that into account I would not run the argument that financially older people suffer as much as those who have taken on mortgages recently. Psychologically though the situation is interesting.

Young people have never before seen a downturn where society tells them they are on their own.

They may have lived through the collective shocks of the GFC and pandemic when we embraced some concept of a team effort and helping each other out. Not this time around.

This time there is no “safe space” to spend time in.

For older folks out there a balancing act is therefore needed when speaking with young people about the economy and the bad things happening.

You’ll feel strongly inclined to point out that things were a lot worse in the past (they were repeatedly in the 1970s and 1980s), but it would be best to remind them that recoveries always come.

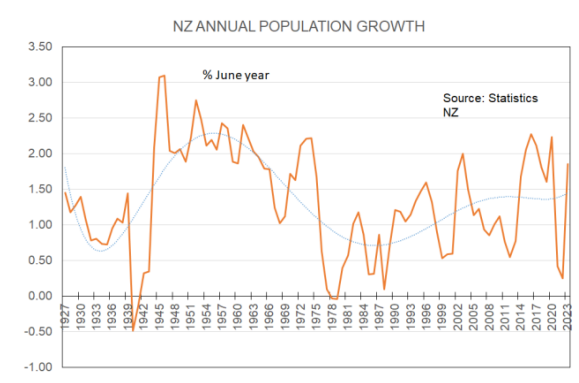

No downturn has ever been so bad that the outflow of Kiwis has caused the population to decline – other than the -0.04% of 1978. The last time it properly did was 1941 associated with WW2.

No downturn has ever removed the long-term trend of house prices upward.

It would also be a good idea to let them know about things which can be done to assist oneself financially during periods of restraint.

This shouldn’t be too hard because many older people in their late working years will already be cutting back their spending.

Why would many be doing this when financially they may be doing just fine? Because, and to coin one of the words used to encourage society’s new victimhood mentality, they are triggered by recessions.

They were born into periods when their parents, relatives, friends lost their jobs and their houses. They have known people who had to go on the dole and seek other assistance. They remember terms like “last one out turn off the light”.

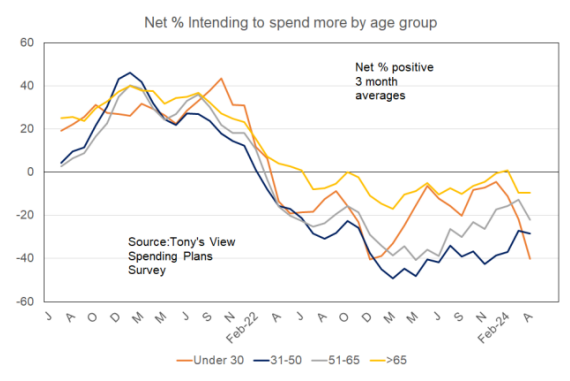

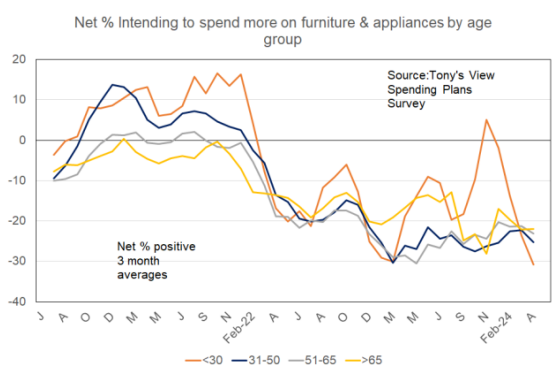

I can see that older pre-retirement people are joining in the spending cutback by looking at results from my monthly Spending Plans Survey broken down by age.

The following graph shows three month averages of spending intentions broken down into four age groups.

The lines show the net proportion of people in each age group planning to buy more stuff in the next 3-6 months. The orange line covers people aged under 31 and the black one is the main mortgage group of 31-50.

The trends in the lines are the similar. But in the most recent months spending plans of people 30 and below shown as the orange line have noticeably deteriorated.

Job fear is likely to be very strong for this group.

No such obvious similar deterioration is there for those older than 30. But note the less weak spending plans as age increases.

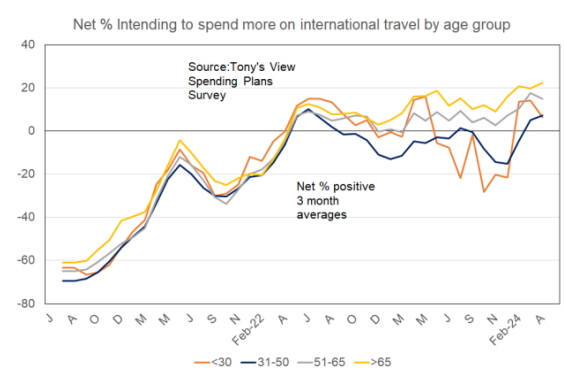

How about some specific areas of spending? The relationship between willingness to spend and age is about the same with retired people firmly indicating intentions to travel offshore.

Is this unusual? Not really. Travelling in retirement is something which has been embraced for as long as I can remember. People are rewarding themselves after 4-5 decades of work and getting to see places they have perhaps long wanted to see before they are too decrepit and incapacitated to do so.

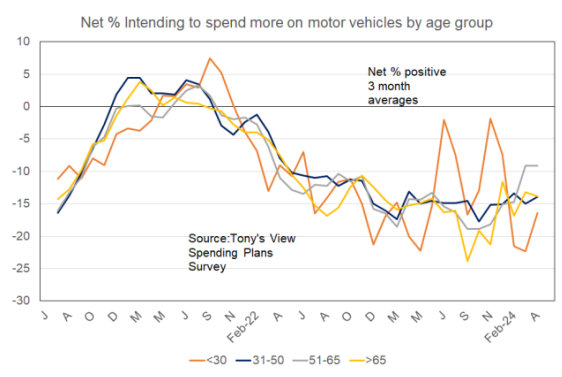

Do we see this same pattern for other large expense items whereby everyone but the retired is pulling back? Not really, but there has been a solid deterioration in car buying plans recently for young people.

Groups are about as pessimistic as each other regarding spending on furniture and appliances.

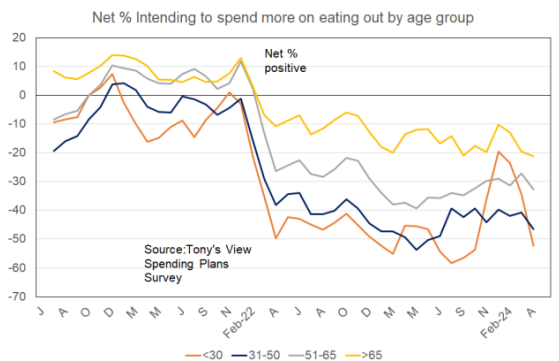

For eating out the spending intentions are definitely correlated with age.

It is fair to say that overall, retired people are cutting back their spending but to a lesser degree than the three younger age groups we cover.

Interest rates:

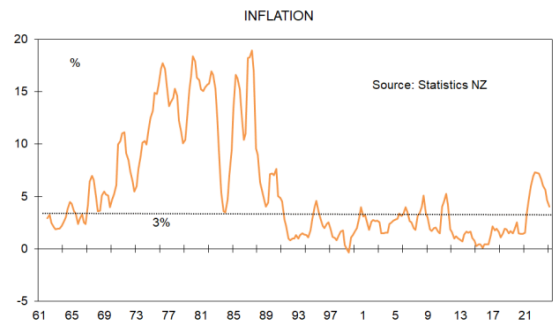

The key statistic released in New Zealand this week was the annual inflation number which came out Wednesday.

Our inflation rate now stands at 4.0% in the year to March from 4.7% three months ago and the peak of 7.3% seen in June quarter 2022.

Inflation is coming down and with the latest quarterly increase of 0.6% following just 0.5% last quarter the annualised rate of increase in prices over the past six months has been just 2.2%.

That is well within the 1-3% target band but borrowers should not get optimistic with regard to monetary policy being eased at any stage in the very near future.

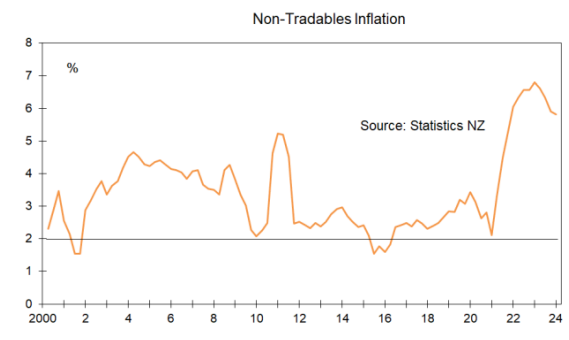

First, the recent two low quarterly CPI increases reflect declines in prices of tradeable goods – things which cross the border.

Tradeables inflation was -0.7% in the March quarter from – 0.3% in the December 2023 quarter.

But the more important non-tradeables quarterly change was 1.6% this latest quarter from 1.1% the previous quarter.

These changes which are more representative of what is happening with pricing decisions in New Zealand are much too high.

The annual rate of non-tradeables inflation stands at just 1.6% but the tradeables rate is 5.8%. This measure of core inflation is nowhere even close to justifying easier monetary policy.

Also signalling no scope for lower interest rates is the core measure where the top and bottom 10% of price changes are trimmed from the calculation. This measure rose 0.8% in the March quarter from 0.7% in the December quarter or 3% annualised these past six months.

This is not too bad but ask anyone if they calculate the increase in their cost of living by excluding the top 10% of their costs which have gone up and you’ll see it isn’t really of much use.

A key contributor to our domestic (non-tradeables/core) inflation is rapidly rising rents. These have increased on average 4.8% in the past year which is the fastest pace of change according to Statistics NZ since the series started in 1999.

This jump in rents will be partly driven by the population boom not being matched by a construction boom, alongside sharply increased costs for those running rental businesses.

One of those costs is council rates which on average have gone up 9.8% in the past year.

This increase comes before the latest round of rates rises announced by our monopoly councils averaging over 15% and stretching to near 25%.

On the basis of yesterday’s numbers there is no reason for expecting that monetary policy will be eased in the next few months.

It perhaps also pays to note the developments internationally whereas the IMF have just noted, good falls in inflation rates seem for now to have stalled.

This stalling and the release of better data on the state of the United States economy has produced some sharp jumps in US wholesale interest rates this week.

These US rate rises have fed through here to some extent and we now have these rates in place.