Cross-posted from Kate Mackenzie at FTAlphaville.

It’s clear to everyone that something big is happening in China.

Double-digit growth is long forgotten and even high single-digit growth is above the consensus (for whatever that’s worth). The implications of this alone are quite massive and you could throw around any number of predictions about what it might mean for commodities, global imbalances, and more. Nomura sees a 30 per cent chance of growth falling below 7 per cent later this year, and Barclays are talking about the odds of growth slowing to as little as 3 per cent growth. Even entertaining the possibility of an outright economic contraction would not get you accused of being a crazed permabear these days.

We had to get here eventually: the signs are only increasing that China’s economy can’t and won’t continue as it has for the past few years. That’s both the composition of the growth and, as we’ll explore below, the rate itself.

The central government leaders recognise things can’t go on as they have been, and talk openly of rebalancing away from the extremely investment-heavy economic mix. They’ve also been keen of late to declare they are comfortable with slower growth — although they seem to be increasingly tentative about that particular message.

It’s probably no coincidence that there’s open talk that this year’s growth target of 7.5 per cent might even be missed; and it’s a target that was already lower than many were expecting. The spike in some interbank lending rates to shocking levels last month caused so much skittishness that it’s hard to believe it was entirely engineered, and a lot of data releases have fallen well short of expectations this year — not least the Q1 GDP. Q2 met lowered expectations — but the details were hardly reassuring.

Does that mean an imminent crisis? Does it mean, for example, a financial crisis, outright GDP contraction, or an overthrow of the regime?

We’re not sure.

What is very difficult about China right now is to see past the signs of slowdown and change (liquidity, property markets, precarious WMPs, etc) and connect them to the underlying shifts: the decline of growth led by exports, demographics and most recently, credit-fuelled investment.

If you like, it’s a question of differentiating between symptoms and the cause.

It’s even harder to predict how this will all play out and in what kind of time frame. What we’ve seen recently appears to be the beginnings of the undoings of the most important current tool for both driving growth and creating imbalance — liquidity and credit.

To explain why, let’s go back to the beginning of the imbalance/slowdown argument.

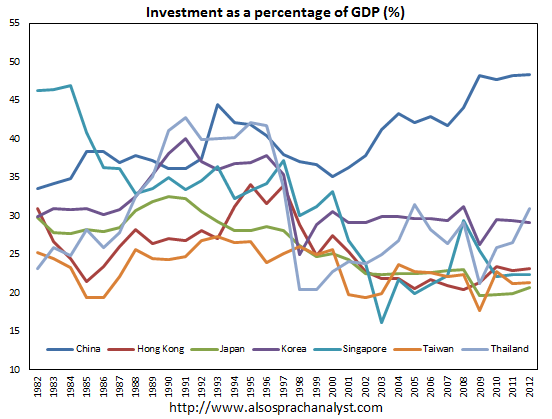

For this, we at FT AV (and increasingly, everyone else too) like to use Michael Pettis’ analysis, which is based around the economy’s ratio of investment and consumption. The investment share of China’s GDP jumped from a extremely high 42 per cent in 2007 to an absolutely amazing 48 per cent in 2010. To understand why this is an amazing, and extremely precarious, level, read Martin’s column or see Pettis himselfhere and here. In short, it’s unprecedented and unsustainable.

Here’s the unprecedented bit (via AlsoSprachAnalyst, based on IMF data):

Here’s the unsustainable bit – its capital is yielding historically low and decreasing returns:

Other favourite arguments for why China’s investment-heavy model can work are itsurbanisation drive, and its low capital stock per capita relative to developed countries. Both are red herrings.

The problem is, infrastructure has driven an increasingly large proportion of GDPgrowth for some time now. In order to maintain growth at anything like recent rates,and rebalance away from the excessive ratio of debt-fuelled investment, Chinese consumption would have to grow phenomenally fast to pick up the slack. In his December 9 newsletter, Pettis gave the example of investment falling 10 percentage points in five years. (He also had misgivings that 10 percentage points wasn’t enough of a shift, and that the country doesn’t actually have five years in which to achieve this without risking a financial crisis.) Pettis continues:

Chinese investment must grow at a much lower rate than GDP for this to happen. How much lower? The arithmetic is simple. It depends on what we assume GDP growth will be over the next five years, but investment has to grow by roughly 4.5 percentage points or more below the GDP growth rate for this condition to be met.

If Chinese GDP grows at 7%, in other words, Chinese investment must grow at 2.3%. If China grows at 5%, investment must grow at 0.4%. And if China grows at 3%, which is much closer to my ten-year view, investment growth must actually contract by 1.5%. Only in this way will investment drop by ten percentage points as a share of GDP in the next five years.

The conclusion should be obvious, but to many analysts, especially on the sell side, it probably needs nonetheless to be spelled out. Any meaningful rebalancing in China’s extraordinary rate of overinvestment is only consistent with a very sharp reduction in the growth rate of investment, and perhaps even a contraction in investment growth.

As an FT AV reader wrote to us, “China has turned “growth” on its head”. Investment has been driving growth, instead of vice versa.

To achieve this, the Chinese Communist Party has deliberately suppressed household consumption, through various capital measures. These measures are heavily linked to the broader political and social policy agendas and are extremely difficult to undo quickly, without upsetting all kinds of vested interests who benefit from the current setup — everyone from big state-owned enterprises to local governments making money on property development to middle-class urban dwellers who don’t want their kids competing with rural migrants for school places.

Back to where we are now. The Q2 GDP number and the associated data suggest the worst of both worlds. Growth is slowing — the number itself looks particularly questionable this quarter — but the rebalancing is not taking place. Just look at this chart from Capital Economics if you’re not sure:

Meanwhile, the flourishing, creative growth of China’s shadow banking sector in the past few years hasn’t been an accident. It is simply the effect of large amounts of liquidity being put into an economy with narrow and restrictive rules on formal banks. The People’s Bank of China might be feeling increasingly uncomfortable with shadow banking risks, but it’s been tacitly condoned for years, not least because is supports growth in the large segments of the economy which can’t get loans from banks.

The liquidity problems, WMP managers scrambling to cover redemptions, Ordoshaving to borrow money to pay wages — these are symptoms.

They’re serious symptoms. Reuters has a great exploration of how much more volatile and unsettling things could get if/as the authorities pursue the kinds of financial reforms that they’ve already outlined. Jim Chanos argues property price falls could spark middle class unrest and allowing banks more freedom to set lending and deposit rates could mean a scramble to gain deposits. Quartz’s Matt Phillips also looks at the scary implications of China’s capital inflows reversing. Likewise, WMP failures could spark bank runs.

In fact, incidents like this have happened before. Look at protests over a defaulted WMP in Shanghai branch of Huaxia Bank in late 2012, the debt crisis in Wenzhou inlate 2011, rolling over the majority of local government debt. So far, the authorities have found ways to limit the damage well short of some kind of mass uprising that would threaten the Communist Party’s control.

Aside from all that, remember there is already massive unhappiness in China about pollution and land seizures. China is estimated to see hundreds of riots every day, on average; few of which you’ve heard about. The reasons they don’t spill over into regime challenge are beyond the scope of this blog, but here’s an explanation. And remember this is a country in which the government has a greater degree of control over the banking system, the media and the internet than most of its counterparts. The rule of law and property rights are notoriously weak. Rural migrants to cities have fewer rights than their urban-hukou counterparts. And so on. It’s a cliche — probably a true one — that economic growth has been the trade-off for Chinese people to forego democratic and other rights. But is anyone willing to make a call on exactly how long this can go on, or what might happen if/when it all comes undone?

That’s not to underplay the significance of capital flows, which could be called a ‘symptom’, but is arguably one that does give a bit of insight into how well the Chinese government might maintain stability. Foreign capital flows, and China’s foreign currency reserves, are key elements of China’s capital controls and its domestic monetary policy.

Victor Shih of Northwestern University estimated in 2011 that outflows totalling $1tn could be problematic for China’s banking system. But even then, the PBoC could redeem its outstanding bonds, wind back repo operations, and/or cut the required reserve ratio (RRR) if it wanted to pump in more liquidity.

There are of course real constraints on how much longer China’s central government can perpetuate the unbalanced, fast-growth model. Employment is an obvious mechanism for economic slowdown to result in unrest. Yet the ageing population demographic seems to be taking care of that a little earlier than anyone expected. Again, it could change. The ‘employment’ segment of the manufacturing PMIs have been weak for some time. Consumer prices are another — although price controls,strategic pork reserves and the like can probably be deployed to some extent.

Essentially, the point is not so much that ‘China is different’. China can handle many things differently, as its unique approach to growth has already demonstrated. But ultimately, it all ends up being another form of can-kicking. Which, in itself, is not so ‘different’.