There have been changes proposed by the Labor party to imputation credits. We have put together a quick series looking at a number of aspects for investors:

- In Part 1 (link) we looked at the winners and losers from the proposed changes

- In Part 2 we look at some peripheral issues (a) at how management cheat by using buybacks (link) to inflate the value of their own options (b) the tax effectiveness of international shares for Australian investors (link).

- In Part 3 (link) tax decisions that Australian investors should consider – can you get in front of any changes?

- In Part 4 (this post) how companies allocate capital and how franking distorts the process for Australian companies

Dividend Imputation – is it distorting Australian Capital?

There have been changes proposed by the Labor party to imputation credits. There is a lot of debate about the pros and cons for investors, the other relevant question is whether imputation credits have distorted the capital allocation decision in Australia in a good way or a bad way.

My take is that there are distortions which have a positive effect on capital allocation in Australia, but the distortions are not as significant as they look at face value.

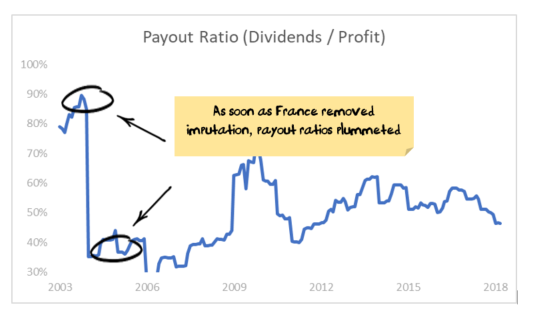

I expect the changes proposed by Labor would have little effect on the capital allocation decision. The experience from overseas is that when the benefits of franking credits are completely removed, dividend payout ratios fall but there are no conclusive effects on the capital structure.

Given the proposed changes only affect a subset of franking beneficiaries, I expect there would be little change to how Australian companies allocate capital.

Capital Allocation background

My experience is that companies go through the following process:

1. Start with Free Cashflow1

2. Decide the minimum level of dividend to pay. Usually, this involves paying at least the same dividend as the prior year if possible.

3. Decide how much to invest in growth capital

4. (a) If cashflow is still positive. Decide what to do with the remaining cash between: (i) paying down debt / increasing cash (ii) returning more cash to shareholders via a special dividend, or higher dividend or buying back shares

4. (b) If cashflow is negative. Decide how to fund the shortfall between: (i) increasing debt (ii) raising equity

Capital Allocation effect of imputation credits

In Australia, there is an additional complication: franking credits. Franking credits are of no value to the company and are valued by investors, and so it makes sense for companies to pay a high enough dividend to use all of the franking credits.

This means that for step 2 (above) the process becomes: “pay a dividend to maximise the amount of franking credits paid to shareholders”.

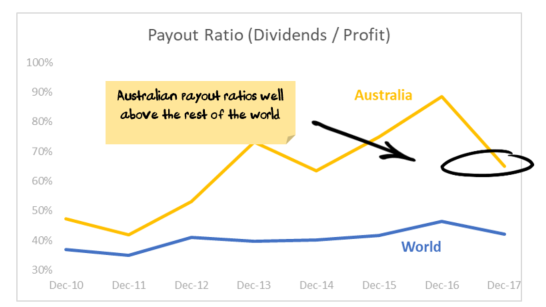

If this was the case you would expect to see a difference in the payout ratio – and there is:

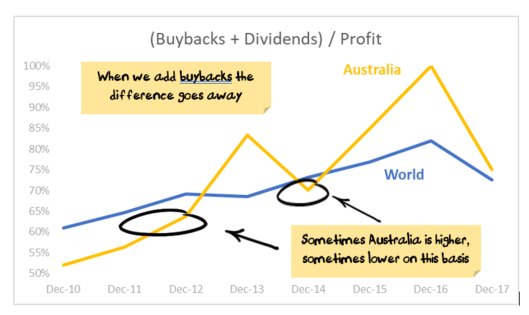

However, this is only half of the story. As you can see in step 4a above, companies return capital to shareholders through dividends or buybacks, and when you add the two together the difference between Australia and the rest of the world goes away:

This indicates that the total payments to shareholders is similar for Australian companies vs the rest of the world – it is just that Australian companies tend to use dividends rather than buy backs.

I also note Australian companies far more frequently have dividend re-investment plans – basically raising capital in order to pay a dividend.

Dividend re-investment plans make sense if you have excess franking credits but can’t afford to pay a dividend – otherwise, dividend re-investment plans are just shuffling deck chairs.

Are buybacks a good thing?

I have a problem with management incentives and buybacks (see post from last week), but excluding that (very solvable) issue, buybacks are not that different to paying dividends except: (1) gains come as capital rather than income (2) buybacks are usually more tax efficient as investors get the returns as capital gains which taxed more concessionally and only taxed when the shares are sold.

From a tax perspective, contrary to popular belief, for most investors there is little difference between owning international shares and Australian shares (link).

Do franking credits result in less tax avoidance?

The studies suggest that for purely domestic companies, yes. For subsidiaries of international companies no.

It does make sense that if domestic companies know that shareholders will receive franking credits then the company would be less likely to avoid the tax.

Also, perhaps more importantly, if a company has a choice of paying tax in either:

- another country at a lower rate but receive no franking credits or

- in Australia at a higher tax rate but receive franking credits

then it does make sense to pay the tax in Australia (up to a point).

Anecdotal evidence also suggests that for some companies it may be worth bringing forward tax payments in order to create franking credits that can then be paid to shareholders.

However, none of this makes sense for foreign companies. And the studies concur.

So, its a positive that having franking results in less tax avoidance from Australian companies. The foreign companies avoiding tax were probably going to avoid tax regardless of whether Australia has franking credits or not.

International Experience

Australia is one of the few countries internationally that has dividend imputation. However, quite helpfully if you are interested in looking at changes there were seven European countries that had dividend imputation and then removed it after joining the European Union including Germany, France and Spain.

This provides a useful backdrop as we can now see the effect that removing dividend imputation had on companies in those regions.

However, when looking at capital structure, there appear to be no difference in capital structure pre-imputation credits vs post imputation in the countries affected.

I view this as further support of the view that companies are making capital expenditure decisions separately from the return of capital decisions.

Capital Expenditure Effects

There is a whole topic hidden here so I’ll just touch on the key points.

Falling capital expenditure

Capital expenditure (capex) has been falling for fifty years. Some lament this as being a symptom of too much focus on short term profits – I’m not convinced we have enough evidence to draw conclusions.

At the same time, the proportion of manufacturing has been falling. Also, many manufacturers have been outsourcing large parts of their supply chain – for example, Boeing outsourced over 70% of the 787 supply chain vs closer to 35% for the 747, which means more and more of the value that Boeing adds is from services. Service companies do not need to spend much on capital expenditure.

It may be that higher payments to shareholders is depressing capital expenditure, or it may be that structural changes are depressing capital expenditure, it is hard to tell. I’m yet to see a study that separates the two components effectively enough to draw conclusions.

Poor returns on acquisitions

A number of studies conclude that for large capitalisation companies that acquisitions in aggregate destroy value (small companies are different).

Having capital constraints therefore helps. The decision process to raise debt or equity to undertake an acquisition is presumably more detailed than to spend cash that is just sitting on the balance sheet. This is a vote in favour of franking, as higher payout ratios will mean that Australian companies will need to raise debt or equity more frequently.

Secondly, for Australian companies the availability of franking credits makes domestic investment more attractive than international.

Therefore franking is probably helpful at the margin.

Valuation

There are no end of studies addressing the valuation of franking credits.

The net effect is that they are valued somewhere between 0% and 50% – this is likely due to a mix of timing (franking credits are not paid immediately) and foreign shareholders (who get no benefit).

Presumably the removal of franking credit refund will reduce this number at least a little.

Corporate Debt market

Australia has a very small corporate debt market relative to the size of our economy and equity market.

There is debate over the reasons, but having imputation credits is likely to be a contributor because:

- franking credits make equity more attractive vs than debt for companies (compared to countries without franking)

- franking credits make dividends more attractive for investors vs interest payments from debt

The removal of franking credit refund should slightly tilt the playing field back in favour of corporate debt.

Conclusion

Franking credits have distorted the Australian capital allocation, with a distinct preference for higher payout ratios in Australia and fewer buybacks.

However, this is at worst a neutral outcome, and probably a good discipline for Australian companies.

Franking credits are at least partially responsible for the stunted development of Australia’s corporate debt market.

Franking credits have been good for tax receipts, and support investment in Australia by domestic companies.

Labor’s changes are relatively minor, unlikely to make much difference to any of the above.

Footnotes

1. Free cashflow = Cash from operations less replacement or required capital expenditure (i.e. capital replacing existing plant & equipment or capital needed to keep the business operating at current levels).

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Integrity Private Wealth Pty Ltd, AFSL 436298.