By now if you’re reading you ought to understand that the Australian economy operates on symbiotic halves. Our miners sell dirt to foreigners and our banks leverage that income in global markets to lend into huge domestic mortgages. When trouble strikes, the Federal Budget sits between them, taking in the commodity tax revenues, and guaranteeing the offshore borrowing of the banks.

There are a number of things that can go wrong with what has been a very successful growth model:

- asset price imbalances can accumulate through over-lending;

- households can build up too much leverage and eventually interest rates hit the monetary zero bound;

- banks can become overly large and complex, as well as corrupted by moral hazard;

- the commodity income is volatile and suffers from huge swings, threatening the sovereign rating that supports low bank borrowing costs, and

- external shocks can raise interest rates.

I put it to you that each of these is today in advanced decay or under accumulating pressure. Thus we can say with reasonable confidence that:

- house prices will keep falling as credit is rationed after the royal commission undoes bank corruption, as well as the recognition among regulators that household debt is too high;

- China is going to keep slowing both cyclically and structurally leading to materially lower commodity prices and terms of trade;

- the global business cycle is old and very likely to bust in the foreseeable future delivering an external shock.

So, how does one prepare at this point? Australian policy responses to the above array of risks will be as follows:

- banks will never be allowed to fail but bailing them out will be very expensive;

- it will lead to sovereign downgrades for the Budget;

- bank funding costs will rise and gobble up the last of the RBA’s rate cuts;

- mortgage rates may also rise. At best they are at or near bottom so expect little rate relief in the next global shock;

- some fiscal stimulus can still come but nothing like during the GFC.

Thus, the three cases for Australia ahead to consider are as follows.

Best case:

- China slows only slowly and the terms of trade fall gradually;

- house prices fall 20% in nominal terms and another 10% in real terms over the next five or more years;

- sovereign downgrades happen gradually;

- the RBA cuts the cash rate to 50bps and uses existing liquidity facilities to prop up the banks;

- however, they are choked with bad loans and credit rationing ensures another lost decade;

- the AUD falls to 50 cents.

Base case:

- Chinese growth slows to 3% over the next five years and the terms of trade correct more swiftly;

- house prices fall 30% in nominal terms and 40% in real terms over five years;

- sovereign downgrades keep interest rates higher than is economically viable;

- the RBA is forced to launch quantitative easing to contain mortgage rates;

- the banks are capital constrained lifting lending standards very high, and

- the AUD falls to 45 cents;

Risk case:

- Chinese growth slows to 3% over the next five years and the terms of trade correct more swiftly as the US economy enters a Trump-bust recession;

- global markets reprice Australian bank debt on corruption, toxic assets and sovereign downgrades;

- house prices fall 40% in nominal terms and 50% in real terms over five years;

- the RBA is constrained from launching quantitative easing owing to a collapsing AUD;

- the banks are wiped out and require full recapitalisation and part nationalisation.

In all three scenarios there are three places to hide. The first is Australian bonds which will soar as growth and inflation collapse. However, even these could be at risk in the more extreme outcomes if sovereign downgrades push interest rates higher and bonds lower.

The second place to hide is cash. However, term interest rates will collapse. We do not think it likely that bank deposits will be at risk of “bail-ins” and thus losses but you never know, I suppose, if the more extreme scenarios play out.

The third place to hide is international assets. Offshore investments protect you from crashing local banks, tanking domestic demand while the tumbling AUD provides you with big upside on foreign assets.

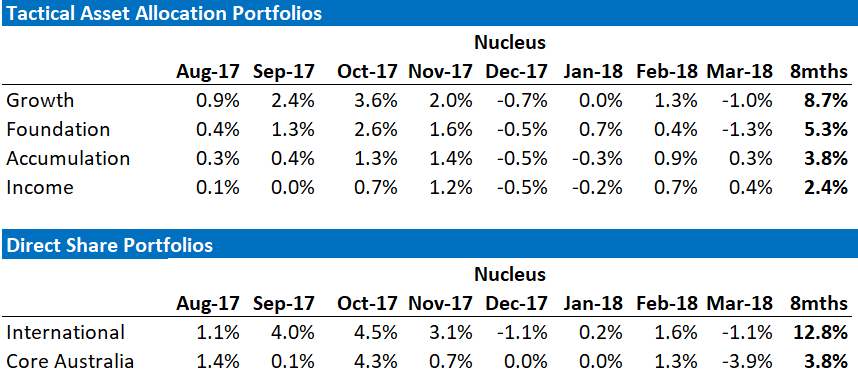

David Llewellyn-Smith is the chief strategist at the MB Fund which offers two options to get your money offshore so he is definitely talking his book. The first option is to use the MB Fund International Stocks Portfolio which is always 100% long as a part of your own asset allocation mix. The second option is to use an MB Fund tactical allocation in which we choose the asset mix for you, including exclusively to international stocks but with bonds and other assets as well to ensure a more conservative mix.

The recent performance of both is below:

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance.