For decades private renters in many countries have spent roughly the same share of income on housing.

Many housing commentators believe that housing rents should fall as a proportion of income over time. Just like the price of clothes and electronic goods, the market for housing is commonly thought to operate in a way that will gradually make rental prices fall relative to incomes.

If only pesky regulations didn’t get in the way. Or so they say.

Here’s an example.

Consumer economics

For example, when incomes rise, households generally buy more clothes or more expensive clothes until they spend roughly the same share of their income on clothes as they did before.

Sometimes, for more luxury items like jewellery or international holidays, the proportion of the household budget spent on these items might rise as income grows.

Where does housing fit in this picture?

There is an element of need when it comes to housing. Just like clothes and food, we can expect that as incomes grow most households spend more on housing rents. How much more depends on the degree to which households choose to substitute towards better quality and more quantity.

The evidence

Here’s the situation in England, where the rent-to-income ratio has been flat since the 1990s.1

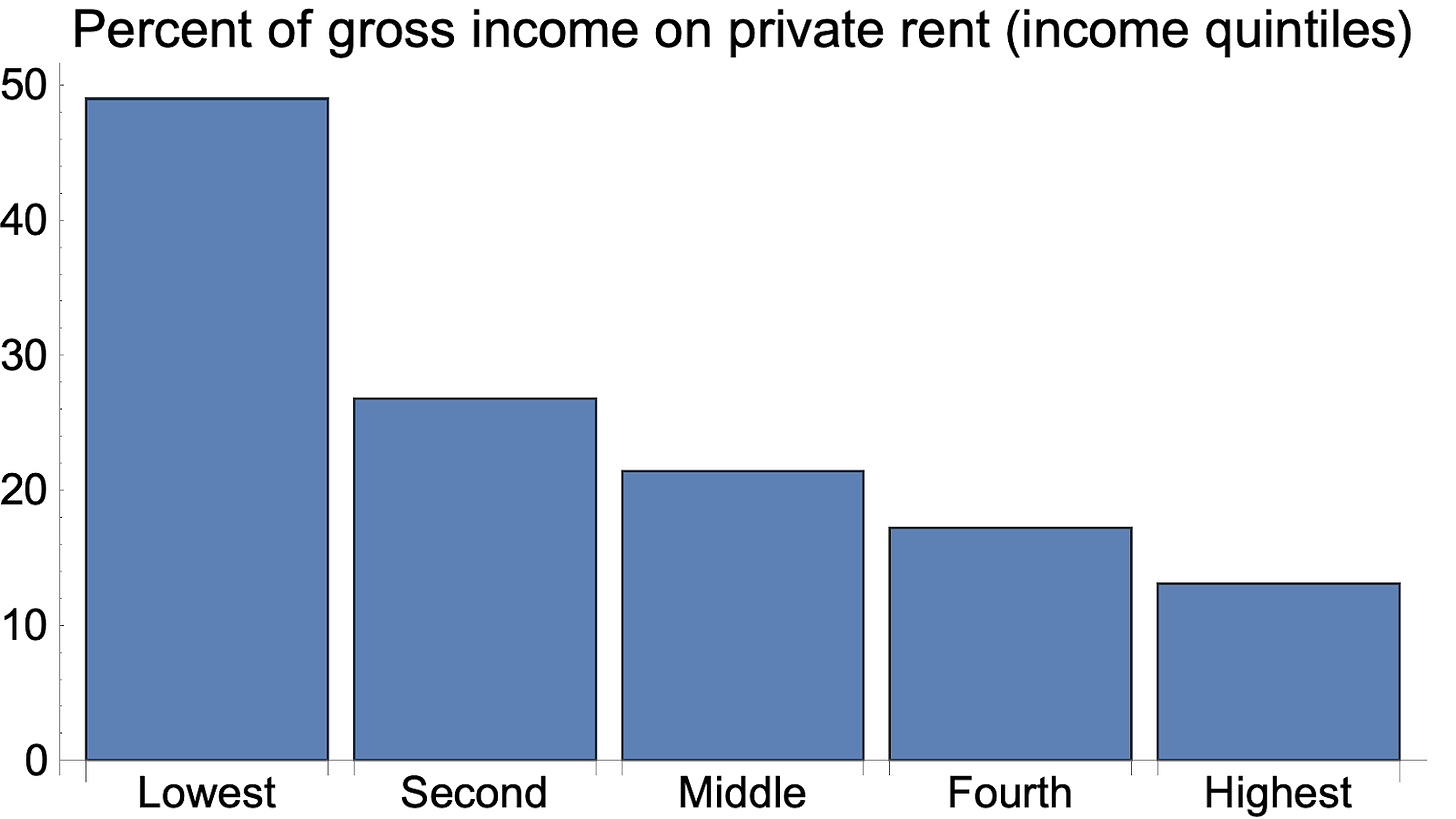

Note that as one household’s income grows relative to all others, they do spend a smaller fraction of their income on housing rents. This is also shown below from Australian data, with the share of income falling from nearly 50% to about 15% as a household moves from the lowest to highest income quintile.

But if we look on average across the market, we see the same decades-long flat line in rent-to-income ratio.

Lastly, we can also see the same pattern in New Zealand since the 1990s.

To be clear, it is true that as one household’s income rises relative to others their rent-to-income ratio falls. But as all incomes rise across the market, the average renter spends the same share of their income on rent.

What if housing rents became cheap?

Imagine if rents suddenly become 5% of household incomes on average, down from the typical 20-30%. What then? What mechanism would keep rents there?

I would argue that immediately households would realise they can move or upgrade to a better home or a better location by spending just a little more, say 7% of their income, to outbid others to rent the better home.

This process of spending more on housing to rent a bigger and/or better dwelling would continue until households found that there was no longer a net benefit to them from giving up other goods and services for more or better housing. Ultimately we would be back to exactly the original budget share being spent on housing rents.

The puzzle happened decades ago

I suspect the lower pre-1980s rent-to-income ratios had something to do with public and council housing options keeping a lid on the private market equilibrium. When you have a cheap outside option, the private market equilibrium shifts. I’ve explained the logic before. Just like central banks manipulate the private pricing of assets by offering an outside option, so too do public housing options shift the private market equilibrium.

However, the change is much larger than I would expect. I sense there are some data inconsistencies in the above England rent-to-income measure. There is more to look into here.

The point is that for going on four decades, the rent-to-income ratio in private rental markets has been flat, and this is what you would expect in a typical market equilibrium for housing.

One of the reasons that the levels of rent-to-income diverge in popular statistics is because of the measures of income being used. For example, sometimes it is gross before-tax incomes, sometimes adjusted for household size, and sometimes net after-tax-and-transfer cash income. Regardless, as long as the income measure is consistent the flat line is usually there.

Dr Cameron Murray is co-author of the Book Game of Mates. Subscribe to his written work at Fresheconomicthinking.substack.com.