By Harry Ottley, Economist at CBA:

Key Points:

- The rental market is very tight with prices rising briskly and vacancy rates extremely low

- The cause of the dislocation is multi-facetted. A shift in household formation dynamics towards smaller household size as a legacy of the pandemic followed by a surge in net overseas migration are the two dominant factors on the demand side.

- The supply of new dwellings has been impacted by the rapid increase in the cash rate, increasing prevalence of short-term rentals and a longer term shortage of completed dwellings.

- There is likely more pain to come for renters in 2023 with the only short term reprieve likely to stem from a partial reversal of the household formation changes.

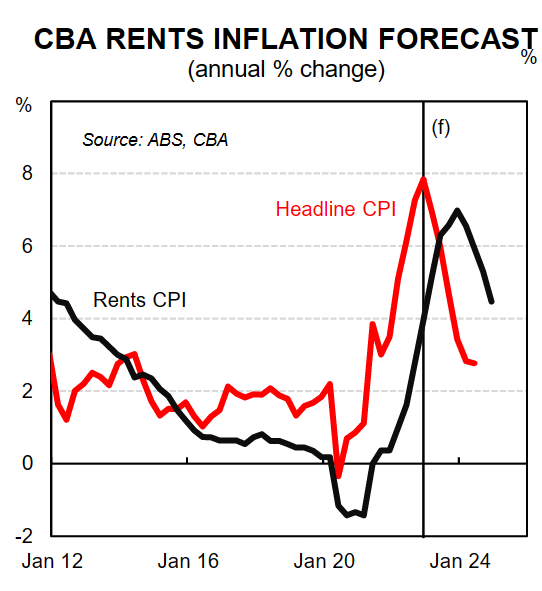

- Increasing rents will be continue even as the pace of headline inflation falls in 2023.

- We expect annual rental inflation to increase to~7% by year end.

Overview

Renting is a critical part of the housing market. Close to a third of all Australian’s are tenants. Having a functional rental system is important for many Australians who don’t own their own home, in various life stages, including students and low income earners.

There has been a notable increase in the media coverage of the rental market in Australia. Reports assert that it is becoming harder for prospective tenants to find a property and the data supports this. Advertised rents are rapidly increasing. Vacancy rates are extremely low across most of the country and rental inflation (which measures price changes in the stock of rents) in the CPI, is rising strongly.

In this note we will take a look at the current state of play in the Australian rental market and the causes for the current stress. Both advertised and paid rental price rises are extremely strong. Vacancy rates across the country are at historically low levels. The surging prices and tight rental markets have been caused by a unique set of circumstances related to the pandemic that have rapidly increased the demand for rentals.

Primarily, these demand side factors have been driven by a reduction in the average household size, followed by a massive and rapid increase in the number of international arrivals coming into the country. This rebound in population growth has surprised on the upside for governments and the RBA.

At the same time, a separate set of factors including rising interest rates, less building activity and more short-term accommodation are impacting on the supply of rentals, creating a dislocated market.

There is unlikely to be respite for renters for the remainder of 2023. A part reversal in the trend of smaller households may alleviate some of the stress, but the rental market will remain tight.

We anticipate rental inflation to rise to ~7%/yr by the end of this year.

The state of play

Rental prices

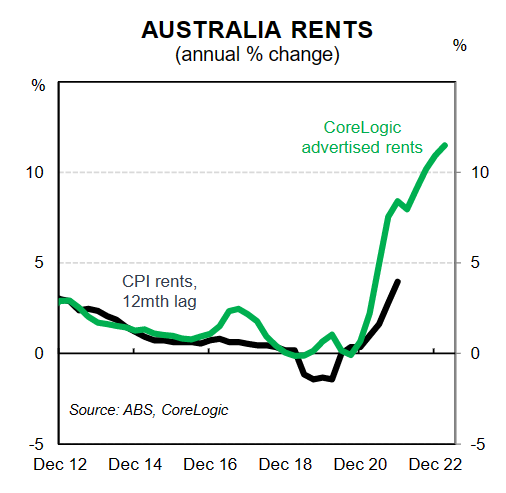

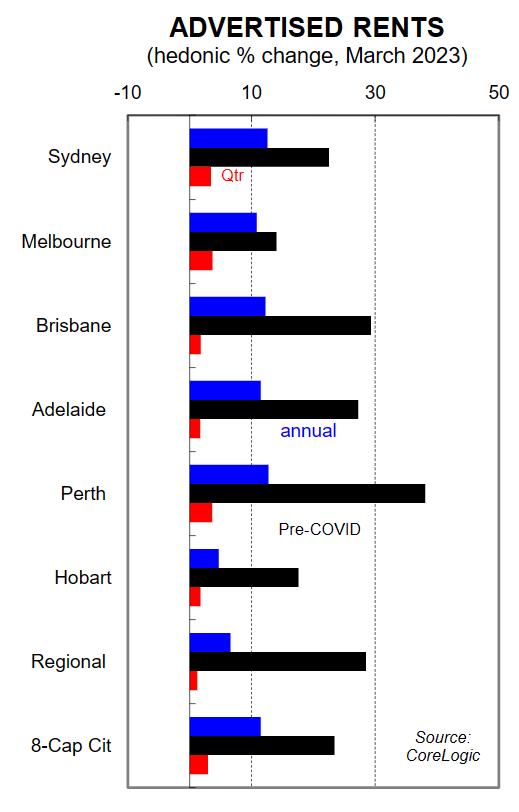

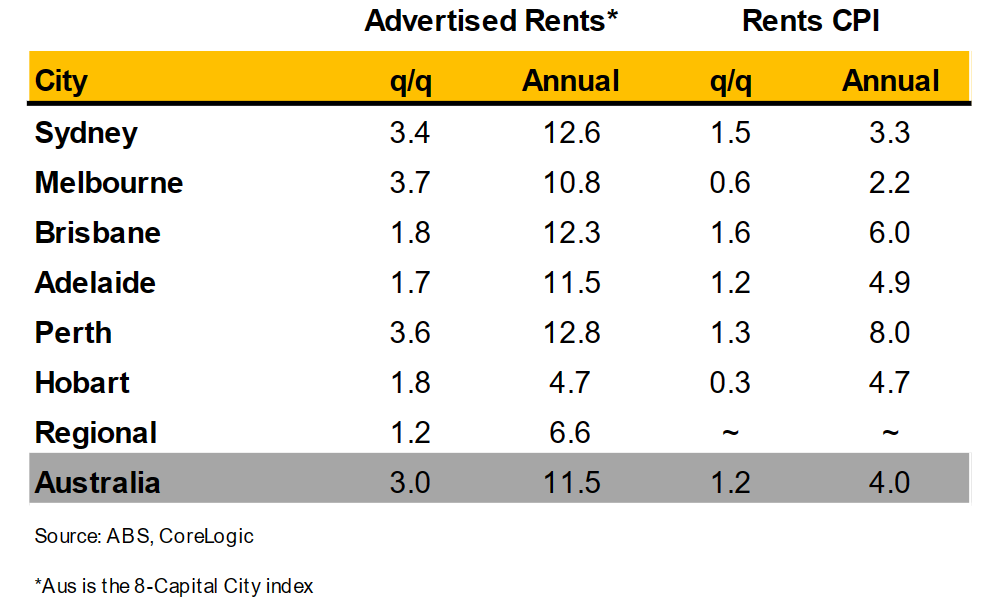

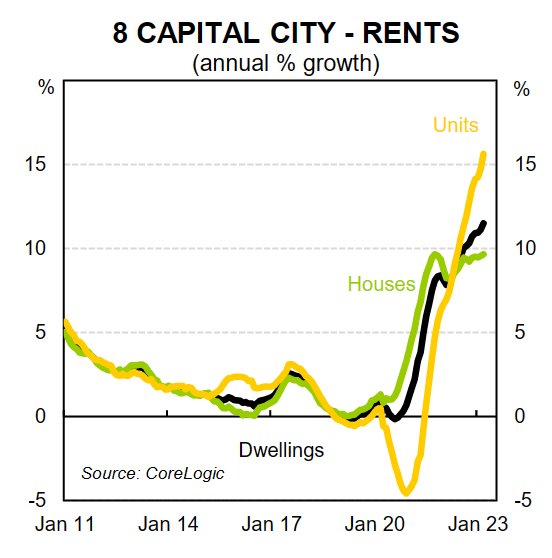

As at March 2023, CoreLogic data indicates that advertised rents in the combined eight capital cities have increased by 11.5% over the year and are a massive 23.4% higher since the onset of the pandemic.

Rent inflation as measured in the CPI (i.e. the stock of rents) is picking up now as well. Increases in advertised rents will take some time to flow in totality through to the CPI measure as most renters are locked into contracts for fixed terms where prices will generally not increase until the lease has expired.

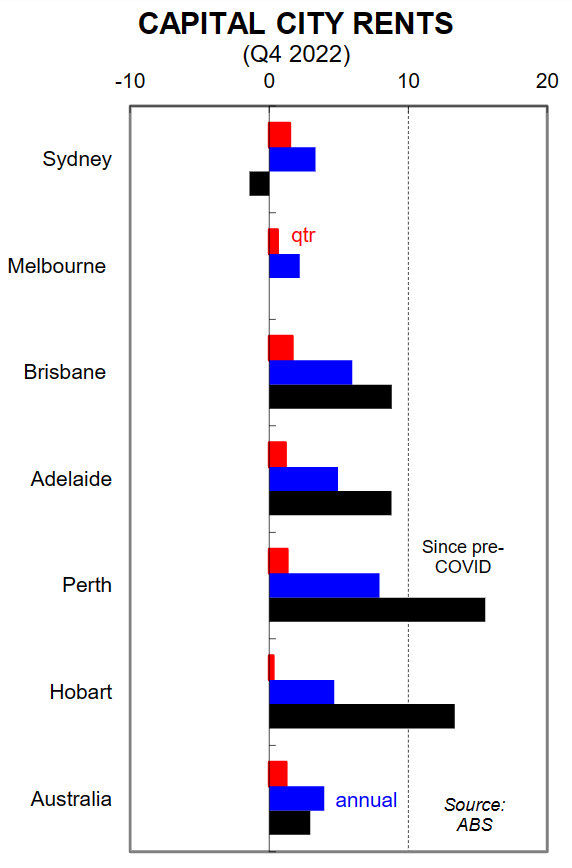

In Q4 22, national rents in the CPI increased by 1.2%/qtr to be 4.0% higher through the year. The annual rate is the highest since 2012. Given the current strength in advertised rents and the tightness of markets, we expect rent inflation to increase further from here and we will detail our forecast towards the end of this note. The monthly CPI indicator put rental inflation at 4.8%/yr in February 2023.

The focus of this note is on capital city markets rather than regional areas. Regional areas of the country did see very strong growth in rents at the start of the pandemic as the search for space and ‘tree change’ effect caused an exodus of city dwellers into the country. This is now partially reversing and for the most part, the pain in the rental system will likely be concentrated in capital cities in 2023 and 2024.

This is especially the case as new migrants are more likely to settle in the capital cities.

The state of play varies depending on which capital city market you are looking at.

In Sydney and Melbourne, the impact has not been as severe as some other parts of the country in terms of rental inflation and tightness of rental markets.

Both of these cities had comparatively weaker population growth through the pandemic due to the combined effect of reduced overseas migrant inflows, and an increase in net interstate migration outflows. This meant there were fewer prospective tenants in these cities, lessening demand and keeping price rises more subdued.

This is likely to have only delayed the inevitable rental growth with a large inflow of migrants already arriving in these two cities since the international border reopened in early 2022. A longer timeframe shows that rental inflation in our two largest cities is not as acute as in the smaller cities. The recent rise in rents in the CPI has only taken rents in Melbourne to their most recent peak in 2017, whilst rents in Sydney remain below the previous peak.

Advertised rents growth, which leads rental inflation in the CPI, has risen strongly in these cities and now has more momentum than the smaller capital cities.

Brisbane has had a different experience to its southern neighbours. Scores of Sydneysiders and Melbournians moved to Qld throughout the pandemic. This large inflow spurred higher demand for housing. The Brisbane housing market was red hot as a result. Dwelling prices rose in excess of 40% compared to the pre-COVID level by mid-2022. Prices then started falling as the national housing market cooled, however the rental market has struggled to cope.

Housing and rental supply is sticky, and the sudden increase in rental demand in Brisbane has pushed prices much higher. Rental prices in Adelaide have also surged. Perth is experiencing rapid growth in rents, but the level remains significantly lower than the mining boom levels.

See below for a table summarising the numbers:

How to determine the state of the rental market – vacancy rates

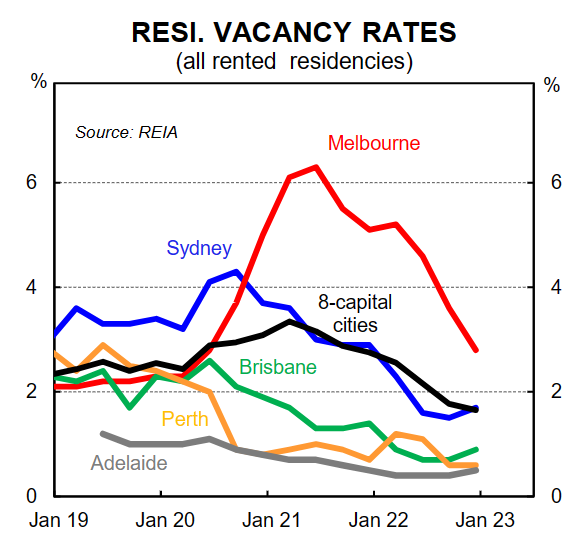

Vacancy rates are the best measure of the underlying balance between rental supply and demand in the market.

As at Q4 2022, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth vacancy rates were extremely low, sitting at 0.9%, 0.5% and 0.6% respectively according to the Real Estate Institute of Australia (REIA).

It is highly unusual for rental markets to be this tight. The last time some Australian cities were experiencing such tight conditions was just before the global financial crisis (GFC), a time when rental prices were also increasing rapidly.

In Sydney, the vacancy rate is 1.7% after reaching a high of 4.3% in Q3 2020. There has been a large inflow of migrants since mid-2022, and a further lift is underway in 2023. This should see the vacancy rate remain low, if not push lower from here. It would not be surprising to see it dip as low as some of the previously discussed cities.

Melbourne remains an outlier of sorts with a vacancy rate of 2.8% which is still below the 3% ‘healthy’ threshold. The combination of much softer population growth due to COVID and above average building approvals over the past decade have likely contributed to Melbourne’s looser rental market. Melbourne’s rental market will tighten from here as population growth strengthens.

In fact, more contemporaneous measures of vacancy rates show Melbourne’s rental market is now just as tight as the other cities.

Domain data for February 2023 on rental vacancy rates has all six state capital cities at under 1%. Adelaide and Perth (0.3%) recorded the tightest market, followed by Brisbane (0.6%), Hobart (0.6%), Melbourne (0.8%) and Sydney (0.9%).

This implies that all capital cities are currently experiencing rental market “stress” in early 2023.

How did we get here? A look at demand and supply

Fundamentals – What drives vacancy rates and rental prices

The RBA recently developed a comprehensive model for the housing market that can assist with understanding what drives changes in the rental market conditions.

Tulip and Saunders (2019) concluded that the dominant factor that determines rent inflation, is the vacancy rate. That is, when the vacancy rate is low, rents rise more quickly.

The rental vacancy rate discussed earlier is the percentage of the stock of rental properties that are vacant.

Generally speaking, a 3% vacancy rate is considered a ‘healthy’ market. The vacancy rate is essentially driven by supply and demand in the rental market.

In Tulip and Saunders’ model, the vacancy rate is driven by ‘excess completions’ which measures how the construction of dwellings (supply) is tracking with population growth and household formation (demand) in the population.

Using the above as a foundation, we can examine how the unique circumstances of the last couple of years has contributed to current situation.

We break the next sections into factors that have impacted the demand for rental properties versus the supply of rental properties.

The demand side -COVID: Closed borders, changes to household formation and re-opening of international borders

The initial stage of the pandemic was a period of intense uncertainty in both the rental market and the broader economy.

In the context of a massive reduction in population growth and concerns about employment and the economy, landlords were eager to secure tenants. As such prices were subdued and even fell in some areas. Interest rates were also cut to record lows.

These market conditions and the impact of policy measures to support renters meant that the rental component of the CPI basket fell in the June and September quarter in 2020.

This is highly unusual and is important to keep in mind when considering the current price surges. They are coming from a lower base than would ordinarily be likely and thus a ‘catch-up’ boost is likely at play.

When vacancy rates are low, demand is outstripping supply, and prices rise. This is what we are seeing now, but the pandemic started with the opposite dynamic.

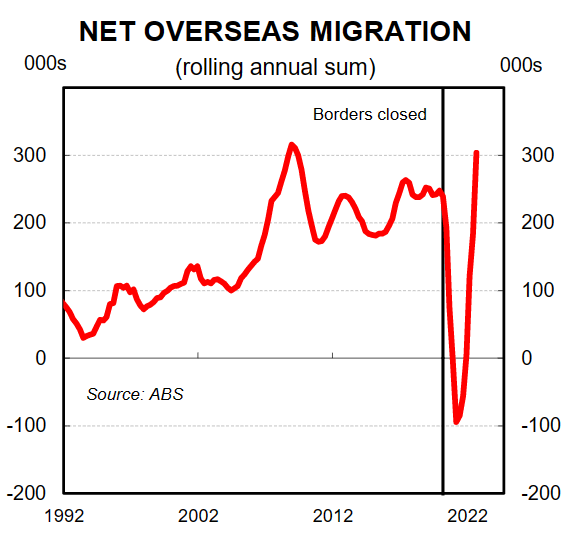

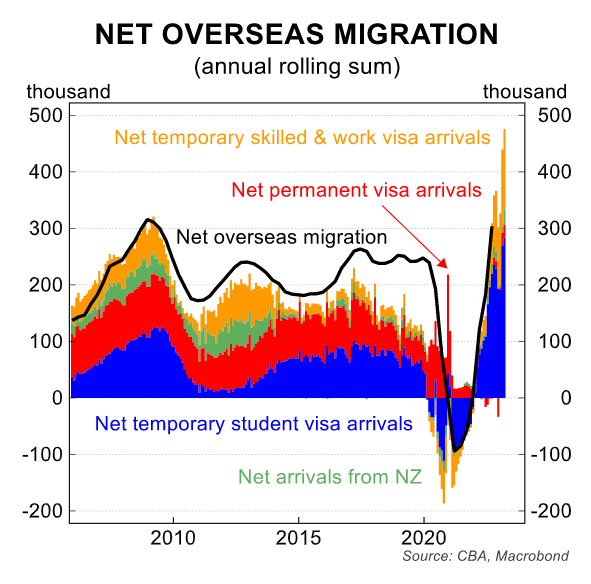

In 2020, a couple of critical forces were influencing the rental market. Firstly, the international borders were closed, causing net overseas migration to go into freefall. It is important to note that overseas migration has been the strongest source of population growth in Australia’s modern history and so the tap turning off had a profound impact on the buoyant recent level of population growth.

Back of the envelope calculations show that by mid-2021, the Australian population was ~400,000 people smaller than forecast in the 2019 Federal budget. In a speech last year, assistant RBA Governor Luci Ellis commented that up to 200,000 households didn’t arrive in Australia due to the pandemic. Clearly, this represents a large reduction in the demand for rentals, especially considering the vast majority of new migrants enter the rental market upon arrival (Khoo, 2012).

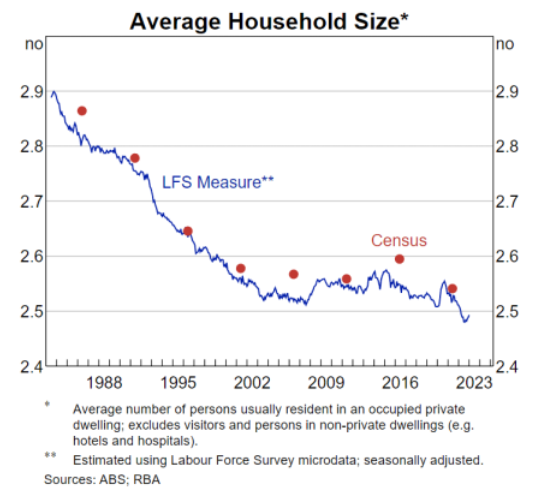

Initially, this meant that rental markets loosened and rental price growth was soft or negative. Critically, this large reduction of demand was offset by the second pandemic force pushing demand for rentals higher. This being a sudden shift in household formation dynamics, specifically the decrease in the average number of people in a household/ residing in a dwelling.

The pandemic caused many in the community to revaluate their living situation, with a desire for more space becoming more important. People working from home needed a spare room and extended time at home with roommates became suboptimal.

Given the rental market was soft at the start of the pandemic while income remained supported by fiscal stimulus, many people could afford the space they desired. The result of all this was a reduction in average household size. The move was abrupt in average household size (AHS) – from a relatively steady state to a quick rise and then a significant levels shift lower.

According to the RBA’s new measure (which broadly lines up with census data), AHS was 2.51 prior to COVID before rising to 2.55 in mid-2020 before falling to a record low of 2.48 in mid-2022.

These may seem like small changes, but it makes a large difference at a macro level. Household dynamics are generally very slow moving and so the sudden change we saw carried a high probability of disrupting how efficiently the rental market was performing.

The pause in net overseas migration however meant the dislocation was delayed. As international borders reopened in 2022, stress began to emerge. By early 2023, the evidence clearly indicates the demand and supply of rentals is severely mismatched across most of the country.

The reopening of international borders has resulted in the rapid increase in long term arrivals into Australia.

The rebound and strength of recent population growth has surprised on the upside. These long term-arrivals, including international students, overwhelmingly tend to rent on the private market. It appears that the rental market is not coping efficiently with this rapid rise.

Supply -Rising interest rates

There is sentiment in the community and some media reporting that the RBA rate hikes have contributed to increased rents. The logic behind this notion being that landlords will pass on their increased mortgage repayments to tenants in the form of higher rent.

However, generally speaking, it is not empirically supported as a key driver of longer term rental prices. Tulip and Saunders (2019) argue that an increase in the cash rate actually decreases rental prices by decreasing employment and aggregate demand, reducing demand for rentals.

That is not to say that the current surge in rental prices has no relationship to the rapid tightening cycle that has occurred. The RBA Governor, Phillip Lowe was recently quizzed about this very topic during his appearance at the Standing Committee on Economics on Friday 17 Feb 2022. Governor Lowe was asked if the interest rate hiking cycle was contributing to pushing up rents. To paraphrase, Lowe said that landlords may be putting rents up in part due to higher mortgage payments but they can only do that in the context of very tight rental markets.

The underlying factor is the vacancy rate, not the rising cash rate. Put another way, if the cash rate was rising but rental conditions were soft, it is highly unlikely that rents would be surging, and vice versa.

Another impact of the cash rate increasing is the disincentive it provides for investors and developers invest in new stock but as we will outline below, this is predominantly a medium term issue.

Supply -Short term rentals

Another factor often cited as a cause for the crunch in the rental market is short-term rentals. The rise of platforms such as Airbnb mean that an increasing portion of the potential rental stock has been converted from long term to short term rentals.

In 2018, the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) conducted a research piece on this notion. AHURI concluded that platforms such as Airbnb do not significantly impact on rental affordability. However, in certain areas that are in high demand and of tourist value, the increased prevalence of short-term rentals is likely impacting on availability and affordability.

In Sydney, the eastern suburbs, Darlinghurst and Manly were all called out as being likely impacted.

In Melbourne, areas such as central Melbourne, Southbank, Fitzroy and St Kilda are called out.

Given the research is now five years old and prior to the pandemic, it is likely the situation has worsened since then as short term rentals become even more widespread.

This finding is likely exacerbated by the fact that these in demand, tourist favoured areas often see much lower growth in the dwelling stock than areas further from the city. Housing shortages are generally most severe in affluent areas.

For example in Sydney, the lowest growth in the dwelling stock occurs in Local Government Areas (LGAs) such as Mosman, Hunters Hill, Woollahra and Randwick (Tulip, 2022).

It stands to reason that these areas of Sydney are also likely to have a larger share of short term rentals than other areas, making housing conditions tighter than they otherwise would be in a pre-Airbnb world.

Outside of these areas and on the market-wide level, short term rentals are unlikely to be the dominant factor in the current rental stress.

Supply – broader housing market dynamics

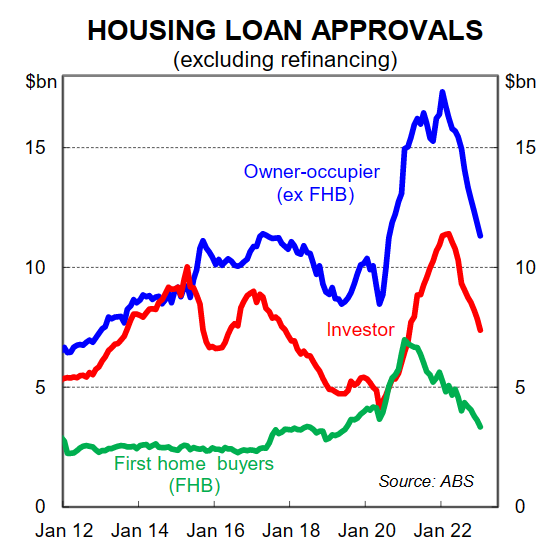

Another common issue reported is the impact of less investors buying into the market, as well as investors selling to secure the capital gains when house prices surged in the pandemic.

However, this argument can be quite circular due to the dynamics of the housing market. For example, there was an increase in the proportion of dwelling sales that were sold by investors.

Data from PropTrack shows this level was around ~25% in late 2021 and was only ~15% prior to the pandemic. However overall turnover in the housing market is lower.

At first glance, this may appear a poor outcome for the rental market given the volume of previously leased properties exiting the market. However, it becomes circular when considering that there was also a spike in the number of first home buyers through this period.

This means that many first home buyers likely left their rental and moved into their home and therefore the impact on rental supply and demand nets out.

If first home buyers are moving straight to their first home from the family home however, this would be a negative for the rental stock.

More investors joining the market, especially by building new homes or investing in new developments, would alleviate some of the tightness in the medium term.

There is a strong pipeline of houses to be built in Australia over the next two years. Investor activity spiked during the pandemic as low rates and policy support incentivised approvals. This will likely help with the stock of rentals in the medium term once these dwellings have been built.

At present, however, lending to investors is falling very quickly, as it is for owner occupiers. If the RBA lowers the cash rate in late 2023, as we forecast, investors may increase activity in the market, enticed again by falling rates and structurally higher rental prices.

Investors selling up likely did have some impact on the current tightness, but it doesn’t appear to be a significant factor. It is also unlikely that investors will ramp up interest in the market with the current market conditions.

When market conditions improve, increased investment activity, especially for multi-unit developments may alleviate some of the rental tightness.

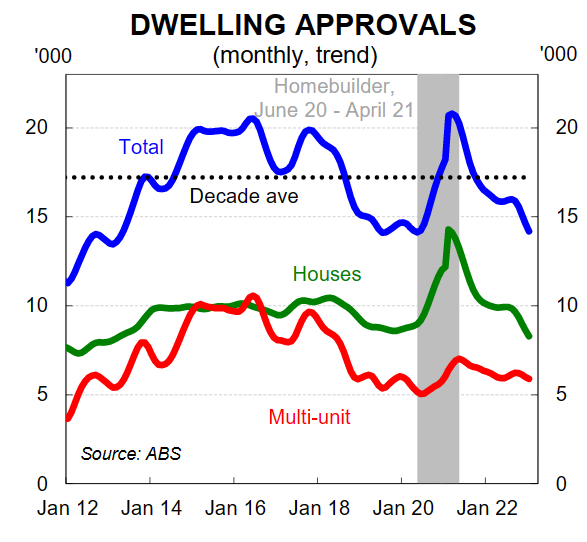

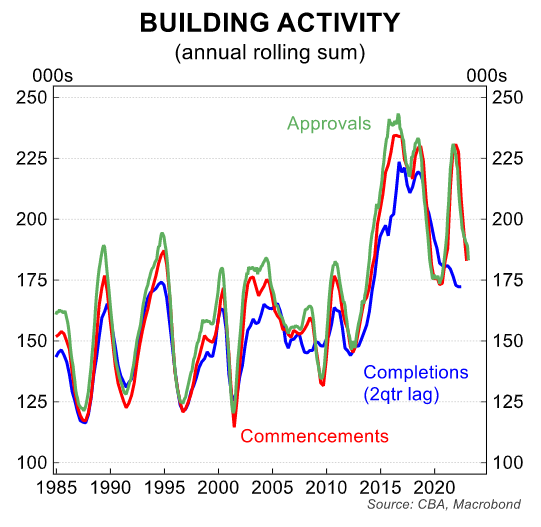

A final important consideration is the level of building activity over the past few years. Low interest rates and the HomeBuilder policy spurred a jump in building approvals in 2020 & 2021. Generally speaking, this jump in approvals was driven by detached houses and not apartments. Multi-unit approvals did rise marginally, but from a lower level than was observed through much of the 2010s.

However the construction industry has been besieged by labour and material shortages which caused delays and prices to rise. This has impacted on how quickly approvals have translated into completions and could mean some projects are delayed or cancelled.

Despite this lift in approvals, the Q4 2022 building activity data shows that there is yet to be a major pick up in the completions of dwellings. There were ~534,000 dwelling units completed from 2020-2022, of which ~329,000 were detached housing and ~202,000 were multi-unit dwellings. This compares to ~636,000 in the three years to in 2017-2019, which included ~344,000 houses and ~287,000 multi-units.

Despite the jump in building approvals for detached dwellings through the pandemic, the growth in the dwelling stock has been softer in the past few years compared to the mid-2010s. This is especially true for multi-unit dwellings which are seeing comparatively stronger growth in advertised rents, an indication of a larger mismatch between supply and demand.

Apartment supply is critical for the supply of rentals. It is estimated that ~50% of approved apartments are made available for renters on completion (RBA, 2023). Given the softer outcomes for apartment approvals and work in the pipeline, increased housing supply in the short to medium term will be difficult to achieve.

Further, the influx of overseas migrants, especially university students is likely to be more concentrated in inner-city areas close to universities which would be exacerbating the constraints on the rental market, especially for apartments.

A final point is that growth in the stock of social and affordable housing is much lower than in previous generations. Low income households that to do not have access to social and affordable housing are forced onto the private rental market, creating additional strain and challenges for society.

The issue of Build to Rent properties, with a focus on social housing continues to be a solution discussed as a way to help solve these challenges in Australia.

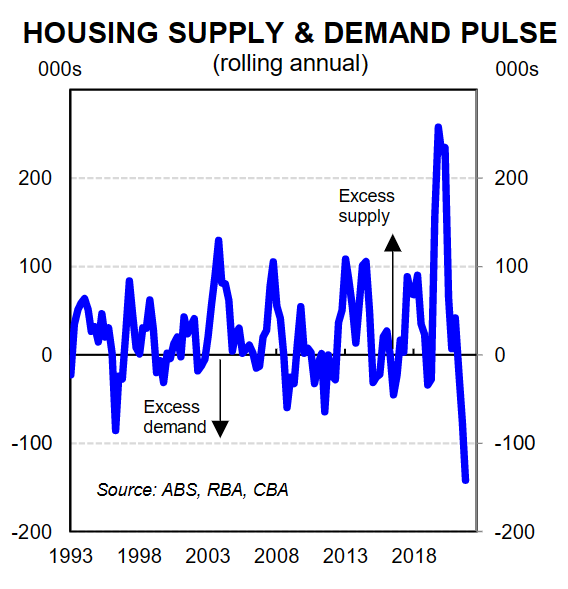

A measure of the pulse of housing supply and demand

Quantitative analysis of the recent shortfall in housing had been challenging because data on household formation is difficult to come by in a timely manner.

The RBA has created a measure for average household size in its most recent Bulletin publication. The calculations remain high-level but based on the population growth from Q4 2020 to Q3 2022 as well the changes to household formation, close to an extra 480,000 dwellings were required. In this time, a total of ~354,000 dwellings were completed, creating a significant shortfall in the supply of dwellings during that period.

Assuming broader rental market dynamics such as the number of new dwellings completed that were to be rented was steady, this was likely a dominant factor in creating a supply and demand mismatch in the rental market.

Using data on building completions and population from the ABS as well as the average household size, we can create a proxy measure of how housing supply and demand are being met.

When the number is below 0, it indicates that demand for housing is outstripping supply. The chart shows how intense the effect of the pandemic was. First there was a period where supply was outpacing demand as international borders were closed and the AHS briefly rose. Then, people spread out and the return of international migration led to higher population growth, causing housing demand to outstrip supply. This has had the flow on effect of tightening rental markets, pushing rental inflation higher.

This data only goes to Q3 2022 and so there is likely to be a sustained period on this measure when demand is outstripping supply. In our view, this has been the dominant near term factor in driving the rental stress we are seeing.

Unprecedented swings in dynamics critical to the rental market occurred in a short space of time and this has created significant stress in the market.

What will happen in 2023

There are many moving parts when it comes to the current stress in the rental market and how this will continue to unfold in 2023.

The dominant factor in our view is the demand impact of the change in household formation that occurred when the pandemic hit. This is being compounded by the surge in international arrivals into Australia (without a subsequent lift in departures).

In Q3 2022, a record number of long term migrants arrived in Australia (~106,000). This has the effect of rapidly increasing the demand for rentals as most new arrivals tend to be renters. There is evidence that household size is beginning to increase again.

These two factors have meant supply constraints such as a longer term reduction in new dwelling stock coming online to create the current dislocation. The impact of rising interest rates and increasing prevalence of short term rentals is further adding to pressure on the system.

Unfortunately, these factors driving the current tight rental are unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

Vacancy rates in Sydney and Melbourne have room to go lower according to some measures, but are already less than 1% in others. Smaller cities such as Brisbane and Adelaide have a vacancy rate at record lows and are under immense stress already.

One positive factor is that most international arrivals tend to arrive in Sydney and Melbourne where there is more (albeit limited) spare capacity in the market.

It is most likely that the rental market will gain the most respite if COVID induced trends start to reverse. This is most likely through the channel of average household size increasing, a sentiment echoed recently by the RBA Governor. That could occur through more people moving back into share houses, people living alone sub-letting out a room or moving back to a family home.

If the average household size increased back to the pre-covid level by March 2023 and population growth was assumed to be the same as Q3 2022, the impact would be close to 65,000 fewer dwellings required to house the Australian population.

In the longer term, increasing the supply of dwellings is important for housing affordability and the rental market with higher density projects of critical importance.

We expect pain will continue for renters throughout 2023 with rental markets remaining tight or tightening further from here. This means rental inflation will be strong, and tenants will be directing more of their disposable income to their housing costs, dampening household consumption.

While the current conditions may incentivise some investors and developers to enter the market to buy, high building costs and high interest rates are probably a stronger disincentive at this time, as well as continued issues around the planning process.

The upshot of this being that supply is likely to remain sticky and renters in the market will have to respond to the constraints by reversing some of the aforementioned household formation dynamics.

Macroeconomic implications –Inflation

Our view is that headline inflation peaked in Australia in Q4 2022. We forecast headline inflation to ease throughout 2023 to be 3.4%/yr at Q4 2023.

Rental inflation is likely to keep picking up and be a countervailing force as headline inflation comes down this year.

Rents currently make up 5.75% for the CPI basket. This makes it the second largest component of the housing part of the CPI behind new dwelling purchases. As such, rents continuing to rise will place upward pressure on headline inflation but we expect disinflation in other parts of the CPI basket to pull the overall rate of inflation lower.

Based on the current vacancy rates as well as the rise in advertised rents, we expect rental inflation in the CPI to rise to around ~7%/yr by year end 2023. This would put the rate of rental inflation to levels not seen for around 15 years.