When the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) began to be rolled out in 2016, we warned it would draw a legion of scammers and middlemen looking to take a piece of the lucrative honey pot on offer.

Similar rorting was already observed under the private vocational education and training (VET) and pink batts program, alongside childcare subsidies.

In 2018, a dedicated 100-officer fraud task force was established by the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA), which oversees the NDIS, to look into more than 500 claims of fraud or “sharp practice,” including instances in which tens of thousands of dollars had been “siphoned” from support packages.

Criminal syndicates were also found to have defrauded the NDIS of millions of dollars.

In 2022, Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission chief Michael Phelan called for a new multi-agency taskforce to tackle the rorting of the NDIS by organised crime.

This Fraud Fusion Taskforce, created in October, has 38 investigations under way involving more than $300 million in payments, and is receiving more than 1700 tip-offs a month about people trying to rip off the NDIS.

With this background in mind, NDIS Minister Bill Shorten will use a National Press Club speech on Tuesday to state that the NDIS is in significant need of a ‘reboot’, although he will insist that the scheme is “here to stay”.

“It will take time and require the kind of collective effort you showed during the campaign to fight for the NDIS in the first place”, Shorten will say according to extracts of his speech at The AFR.

He will speak of unethical service providers using the disabled as “cash cows” to line their own pockets and damage the reputation of the entire industry.

Possible changes to the NDIS that the federal government has in mind are likely to include shifting participants to longer-term plans rather than annual ones that increase in cost each year, and linking funding to achieving results for participants, rather than on the volume of services provided.

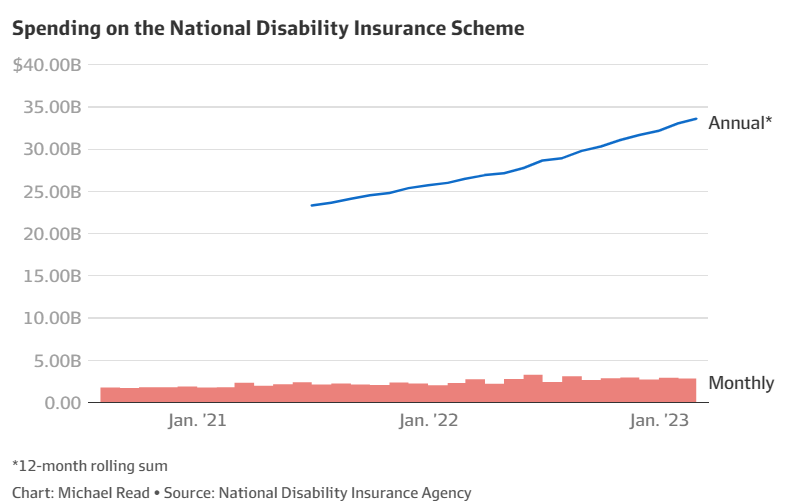

It was originally hoped that at most the NDIS would cost around $25 billion a year, but it is expected to cost $35.5 billion in 2022-23 and overtake Medicare spending:

In February, The Australian’s social affairs editor Stephen Lunn revealed children were being diagnosed with more severe autism than their characteristics warranted to give them a greater chance of securing a place in the NDIS. This has fuelled further funding pressure.

Andrew Whitehouse, professor of autism research at the Telethon Kids Institute and the University of Western Australia, told The Australian: “It is without question that clinical behaviour has become biased towards making certain levels of an autism diagnosis in order to provide families a better chance at receiving the support they need through the NDIS”.

Any $35 billion government scheme is going to have a certain percentage of people doing the wrong thing for personal financial gain. But the rorting of the NDIS is excessive.

The NDIS clearly needs tighter regulation and enforcement to ensure that rorting and fraud are minimised. Funding also needs to be better targeted at people with genuine disabilities.