It is one of Australia’s biggest economic lies: the claim that international education is Australia’s fourth largest export valued at more than $40 billion.

The Age’s View span this lie again on Tuesday when it wrote

“In 2022, international education earned this country $46.7 billion, which in the words of Universities Australia chief Catriona Jackson makes it “the biggest export we don’t source from the ground” – the only more valuable ones being iron ore, coal and natural gas”.

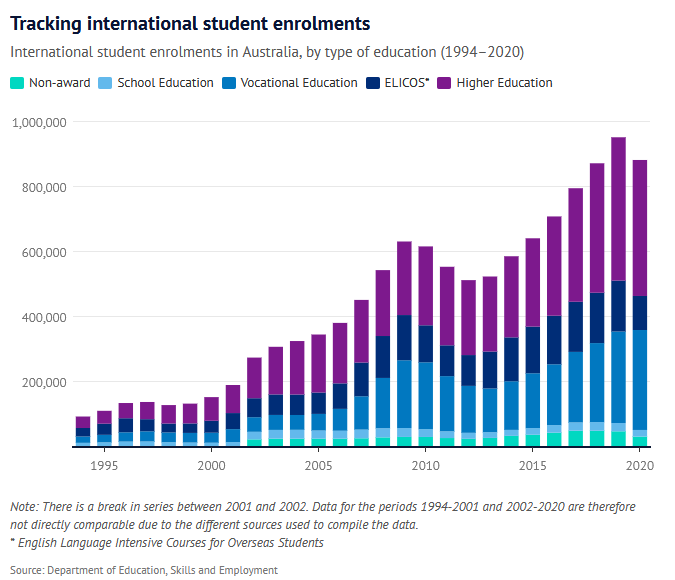

The Age also claimed that international education supported more than 240,000 jobs across the Australian economy, while completely ignoring that foreign students very likely ‘take’ more jobs than they ‘create’, given there were around 900,000 international student enrolments in Australia in 2020 and the majority worked while studying:

The fact that so many students pay for their fees and living costs via working in Australia necessarily means that this expenditure is by definition not an export.

This is especially the case for Indian and Nepalese students, which are Australia’s second and third largest student source behind China.

The Reserve Bank noted in late 2020 that “Australia’s education exports totalled $40 billion in 2019. This included $17 billion in tuition fees paid by international students and $23 billion in international students’ living expenses while they studied in Australia”.

“China has accounted for one third of Australia’s education exports over the past few years (Graph 2)”.

However, the RBA then contradicted itself by stating that most international students – especially those from India and Nepal – work in Australia to pay their expenses:

“Census data indicate that over three quarters of Indian and Nepalese holders of student visas were in the Australian labour force in 2016”.

“Therefore, a lack of part-time work opportunities in Australia – in line with broader spare capacity in Australia’s labour market – could weigh on demand for education exports”.

The 2016 Census showed that the overwhelming majority of students from South Asia (as well as the Philippines and Colombia) undertook paid employment in Australia to support themselves:

Navitas’ recent survey of factors influencing the choice of study destination also showed that most students from South Asia and Sub Saharan Africa care most about work rights, cost of study and permanent residency rather than the quality of education:

In other words, Australia is a popular destination for international students precisely because it offers very generous work rights and opportunities for permanent residency.

Again, money earned through employment in Australia is by definition not an export. Yet, the ABS, Treasury, the education sector and the media continually assert that it is.

As a result, during the pandemic, we witnessed the bizarre circumstance in which thousands of international students begged the government for financial assistance and turned to charities when they lost their jobs.

These students are not exports because it is clear they had to work in Australia to pay for their expenditures.

This fictitious export figure for education also fails to account for money remitted by migrants, especially overseas students, which rose sharply in the years before the pandemic:

Any accurate assessment of international student exports would only include funds arriving in Australia from abroad and would net out funds returned back home via remittances.

Exports are greatly inflated since the ~$47 billion export figure quoted above does neither of these things and incorrectly includes expenditure funded by paid work in Australia.

In light of the above, the financial requirements for international students need to be significantly lifted so they can support themselves while enrolled in their courses and are not reliant on jobs to pay their costs.

There would be four advantages to lifting the financial requirements for international students.

First, it would lessen workplace competition, increasing job and wage prospects for young Australians.

Second, it would lessen wage theft, given international students are the ones routinely exploited.

Thirdly, because tuition and living costs would be covered by funds from overseas rather than by income earned in Australia, it would increase export revenues per student.

Finally, it would improve student quality because more people would travel to Australia to study instead of only to work with the intention of eventually obtaining permanent residency.

Lifting the financial requirements for international students would obviously be opposed by our rent-seeking education sector because it would make obtaining a visa more challenging and slow the flow of students.

It is far easier for the sector to lower the entry bar and privatise the extra tuition fees, while socialising the costs on the Australian public.

The creative accounting and propaganda surrounding education exports plays straight into the hands of the education-migration lobby by inflating its worth.