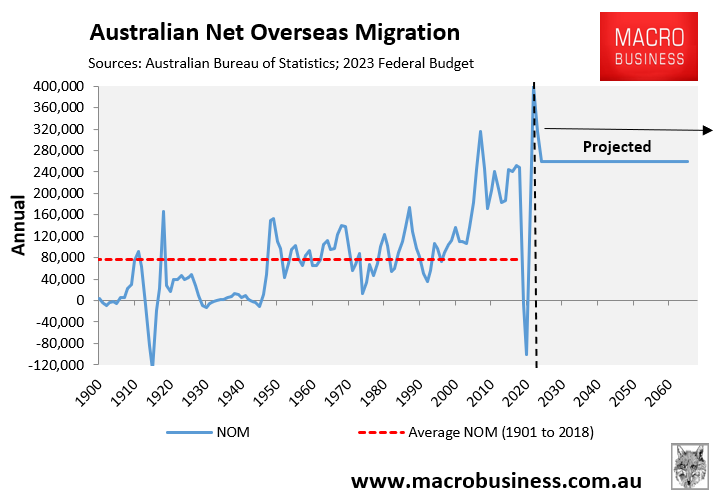

While Australians grapple with one of the worst housing shortages in history, buried deep in the Appendix of Budget Paper 3 was the federal government’s official net overseas migration (NOM) forecast, which has been aggressively increased.

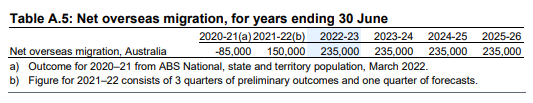

The NOM table from the October 2022 Federal Budget, which forecast 235,000 NOM per year over the four-year forwards projections, is shown below.

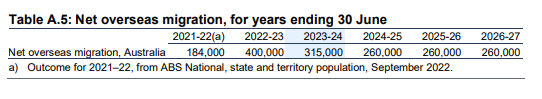

Here is the revised NOM projection from the Federal Budget released on Tuesday:

NOM is now predicted to reach 400,000 for the first time in 2022-23 before slowing to 315,000 in 2023-24. It will then moderate to 260,000, where it will remain over the forwards projections.

Thus, the new Budget has permanently locked in a higher NOM that is 25,000 more than the previous Budget, the 2021 Intergenerational Report, and the 2023 Population Statement.

Despite Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil’s claim that Labor is not delivering a “Big Australia,” the new Federal Budget estimates clearly show otherwise.

This estimated long-term NOM of 260,000 is 40,000 greater than the nation’s ‘Big Australia’ immigration in the 15 years preceding the pandemic, which averaged roughly 220,000 per year.

The Albanese Government has purposefully increased immigration by:

- Extending the number of hours students can work and their stay in Australia after graduation;

- Hiring 500 people to clear the fabricated “one million” visa backlog as quickly as possible;

- Raising the annual permanent non-humanitarian migrant intake to a record high 190,000 (from 160,000); and

- Relaxing entry requirements for Indian students and workers.

A population increase of five Canberra’s in five years means growing housing shortages:

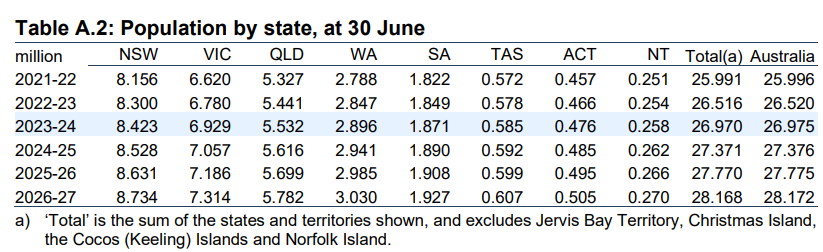

The insanity of Australia’s housing situation is perfectly summarised by the Federal Budget’s population projections, which are seen in the table below.

The population of Australia is expected to grow by 2.18 million people in the five years to 2026-27, or about 435,200 people each year.

To put that statistic into context, it is the equivalent of adding five Canberra’s worth of people to Australia’s current population in only five years, but without the necessary housing and infrastructure.

In other words, it is the equivalent of adding another Perth to Australia’s population in just five years.

Building housing for such a massive rise in population is an impossible undertaking even under ideal housing conditions.

It’s even worse when the entire housing construction sector is on its knees due to widespread insolvencies and skyrocketing materials and financing (interest rate) costs.

According to ASIC data, 1672 home builders have declared bankruptcy so far in 2022-23.

With two months left in the fiscal year, this is the largest number of insolvencies since 1802 building enterprises went bankrupt in 2014.

Among the insolvencies listed above are industry titans such as Porter Davis Homes, which went into administration in March with over 1500 homes partially constructed, as well as a slew of smaller firms.

Since 2021, it is estimated that builders responsible for about 5200 homes worth a total of $2.2 billion have gone bankrupt.

As a result, fewer builders are left to satisfy the nation’s housing needs in the face of unrelenting immigration demand.

This means the housing crisis will worsen, resulting in higher rents and increasing homelessness.

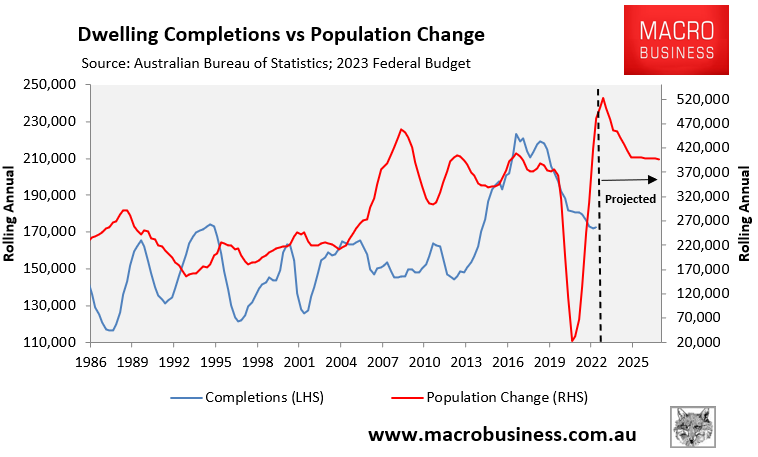

The enormity of Australia’s housing crisis is encapsulated in the following chart, which compares house completions to actual and projected population increase as outlined out in the Federal Budget:

As you can see, Australia did not construct enough homes during the fifteen years of “Big Australia” immigration preceding the pandemic.

The housing supply crisis is now guaranteed to worsen, as real development levels are declining at the same time that Australia is expected to experience record population increase of between 400,000 and 500,000 people each year.

Labor’s supply-side remedies are woefully inadequate:

Federal Housing Minister Julie Collins said during Question Time before the Federal Budget that Australia has a “supply issue” with housing that has been going on for a long time.

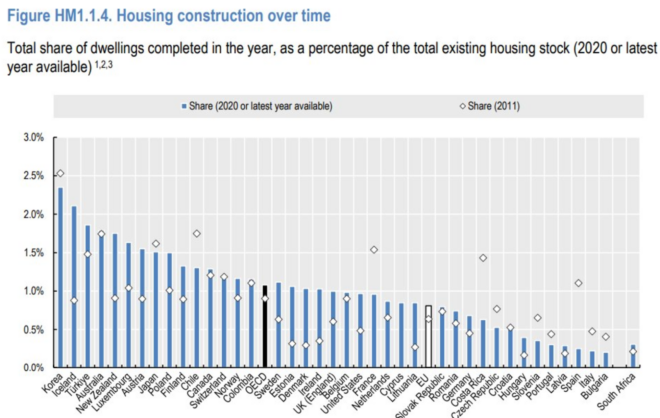

““We have less homes per 1,000 people in Australia than the OECD average”, Collins added.

“Which is why we need to build more, which is what the National Housing Accord is all about”.

The Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF), which will help fund 30,000 extra social and affordable rental homes over its first five years, is the centrepiece of the Albanese Government’s National Housing Accord.

Clearly, the 6,000 new social and affordable dwellings targeted for development each year fade into insignificance in comparison to the projected annual population increase of 400,000 to 500,000 people.

Labor’s HAFF is a “drop in the bucket” that will worsen Australia’s housing shortage in the face of the government’s unprecedented immigration program.

Julie Collins’ remarks about supply are also highly deceptive, given Australia managed to considerably increase construction levels in the years leading up to the pandemic (see chart directly above).

The truth is that Australia has built significantly more dwellings per capita than most other OECD countries:

The problem is that Australia has also run one of the world’s largest immigration programs, ensuring that housing demand has always outpaced supply.

This situation will only worsen if the Budget’s aggressive immigration forecasts come to fruition.

If the Albanese Government truly cared about ending the nation’s housing shortage, it would run an immigration program that was substantially lower than the overall expansion in the housing stock, not the other way around.

It’s time to stop blaming a ‘lack of supply’ and start analysing the housing problem honestly and openly.

Australia will never be able to build enough homes so long as its population continues to grow at such a rapid pace due to high levels of immigration.

Australia’s housing crisis is a direct result of excessive levels of immigration.