Last month we reported that Australia’s international student boom was “built on fraud and grift”, with large numbers of South Asian students arriving only to drop out of established universities and enrol in cheaper private colleges.

The record influx of arrivals is a result of recent policy changes that extended the amount of hours students can work in Australia while “studying”, as well as the number of years they could stay in Australia after graduation.

The Albanese Government also increased the permanent migrant intake to a record high of 195,000 (lowered back to 190,000 in the federal budget), up from 160,000 previously, which has increased the likelihood of students obtaining permanent residency.

The combined policy changes have been a ‘red rag to a bull’ for shady migration agents and students looking to live and work in Australia under the student visa system.

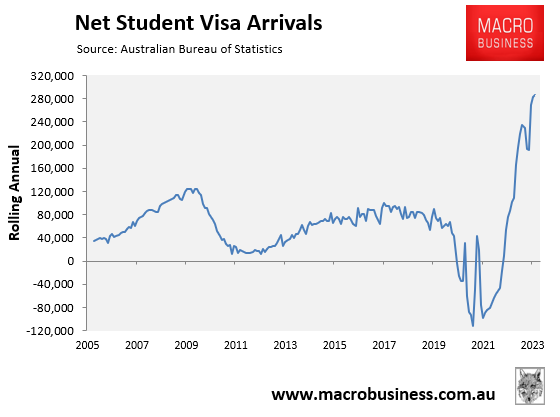

Net student visa arrivals have reached all-time highs, with Indian students driving the increase:

Australia is on track for its largest annual intake of Indian students across universities and vocational courses, topping 2019’s watermark of 75,000.

This boom in student visa arrivals is fuelling Australia’s unprecedented net overseas migration.

The boom in international student arrivals is also being facilitated by unregulated education agents and ‘ghost colleges’.

Specifically, dodgy private colleges have been found to be colluding with unregulated international education agents to steal students from prestigious public institutions for large commissions, to sell work visas, and construct “ghost colleges” where students do not attend classes but are awarded degrees.

These ‘ghost colleges’ then enable migrants to use the student visa system as a backdoor work visa en route to gaining permanent residency.

Last month, it was reported that a surge in applications from South Asian students, as well as an increase in what the Home Affairs Department identified as fraudulent applications, had prompted at least five Australian institutions to impose bans or restrictions on students from specific Indian states.

This surge in fraudulent applications had been driven by unregulated agents, who receive thousands of dollars in commissions for every student they enrol.

With this background in mind, the Brisbane Times reports that the Department of Home Affairs is currently deeming one in four Indian applications for student visas as “fraudulent” or “non-genuine”, in what is the highest rejection rate for Indian applicants in a decade.

The surge in rejections has accompanied a sharp increase in the volume of applications.

It has prompted fresh calls for the regulation of education agents who arrange visas for foreign students, while Federation University in Victoria and Western Sydney University in NSW have banned the recruitment of students from certain Indian states.

“A large number of Indian students who commenced study in 2022 intakes have not remained enrolled, resulting in a significantly high attrition rate”, Western Sydney University told agents in a message sent on 8 May.

“Due to the urgency of this matter, the university has decided to pause recruitment from these regions in India, effective immediately”.

Likewise, Federation University sent a letter to agents stating “the university has observed a significant increase in the proportion of visa applications being refused from some Indian regions by the Department of Home Affairs”.

“We hoped this would prove to be a short-term issue [but] it is now clear there is a trend emerging”.

The federal Department of Education has acknowledged “shady behaviour” in the international education sector, including the provision of inducements to entice students to transfer from universities to less expensive vocational education providers.

Last Monday, the Department of Home Affairs told a federal parliamentary inquiry that Australian institutions were now rejecting 20.1% of applications, up from 12.5% in 2019. The rejection rate for Indian applications is 24.3%, the highest since 2012.

According to Alison Garrod, the assistant secretary from Home Affairs’ temporary visas branch, there has been “an increase in non-genuine applicants and fraud in student visa applications” since the beginning of 2022.

International Education Association of Australia CEO Phil Honeywood, recently claimed Australia’s international education system has become a “Ponzi scheme” for enticing non-genuine students through migration pathways.

Honeywood claimed money was sometimes being “handed in an envelope under the table” to agents who directed young people into courses.

“These agents need to be regulated”, he told Guardian Australia. “It’s not hard to do but they’ve been getting away with it for two decades”.

Last week, Honeywood told the parliamentary inquiry that agents were too often collaborating with the families of Indian students to get them into the country, and he reiterated his call for more regulation.

“We find a lot of parents are desperate to get their child an education outcome in a country like Australia and there is a cultural reliance, particularly on the subcontinent, in the local education agent who by word of mouth has been seen to have successful outcomes”, Honeywood said.

“Often the students are the victim of this same culture of exploitation where you have the offshore agent who has got the cousin with a separate office in Melbourne, maybe with a different company name”.

“And so the offshoring agent takes a commission from the student’s family to get them into the country, and then what often happens is that the cousin based in Melbourne as an onshore agent will then actually poach the same student off the university or the quality private provider and have them placed, for an additional commission, into another provider”.

The decision by the Morrison government in 2020 to remove the 20-hour weekly limit on the amount of work foreign students could do (extended by the Albanese Government at the Jobs & Skills Summit) prompted a surge in the number of applications from South Asia.

Labor will re-introduce a limit as from 1 July, but will increase it to 24 hours (from 20 hours previously).

Thus, when combined with the expansion in how long students can remain in Australia post graduation, Labor has chosen to maintain Australia as a ‘honeypot’ for students seeking to live and work in Australia.

In March, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese also signed an agreement with Indian counterpart Narendra Modi giving “mutual recognition of qualifications between Australia and India”, thereby easing the path of entry to Australia for Indian students and migrants.

Instead of actively encouraging high volumes of low-quality students into Australia, policymakers should instead target a smaller pool of excellent (genuine) students.

This policy reset could be achieved by increasing the financial hurdles for entering Australia, lifting entry standards (especially English language proficiency), and removing the clear link between studying, working and permanent residency.

This qualitative approach to international education would:

- raise student quality;

- increase export income per student;

- improve wages and working conditions;

- reduce enrolment levels to manageable and sustainable levels, thereby improving quality and the learning environment for local students; and

- ease population pressures in our major cities.

Sadly, the Albanese Government has instead opted for volume over quality by trashing entry standards.

We saw the results of this policy approach last decade when youth unemployment, wage theft, exploitation and crush-loaded housing and infrastructure became endemic.

Expect more of the same once more.