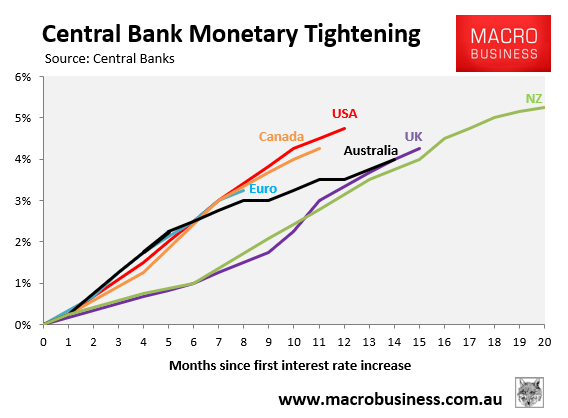

The 4.0% of interest rate hikes by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has been less aggressive than those of New Zealand, the USA, the UK and Canada:

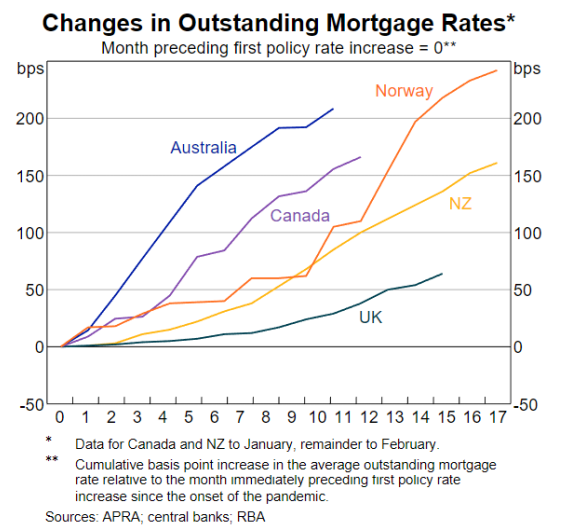

However, the rise in mortgage rates in Australia has been more severe than most other developed nations, as illustrated by the below chart from the RBA:

The oversized mortgage rate increase in Australia is due to the predominance of variable-rate mortgages, which means there is a more powerful monetary policy transmission in Australia than most other countries.

For instance, most home loans in New Zealand have fixed interest rates.

Mortgage rates in the United States are normally set for the entire loan term of 30 years, which is why it isn’t even included on the RBA chart directly above.

As a result, mortgage holders in most other countries are not affected to the same extent as Australians when official interest rates rise (or fall).

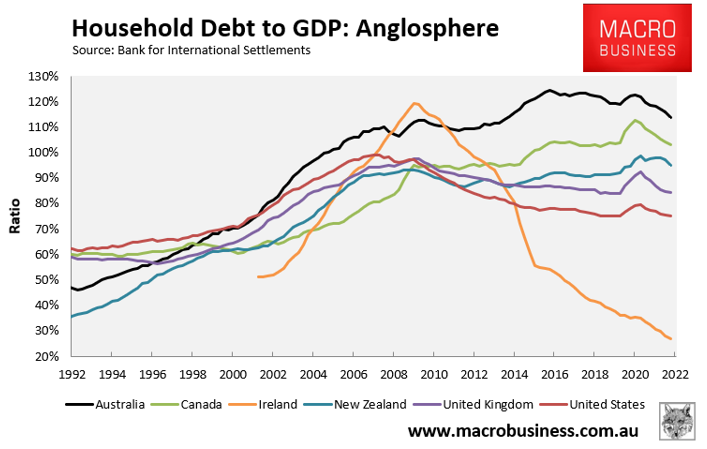

Aussies are choking on debt:

To make matters worse, Australian homeowners carry the world’s second largest mortgages, after only Switzerland.

The chart below compares the ratio of household debt to GDP (gross domestic product) among English-speaking countries and demonstrates that Australia is far ahead of its English-speaking peers:

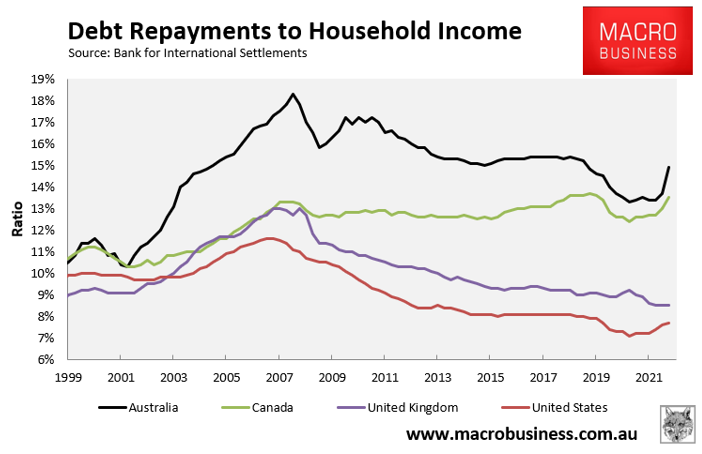

Actual debt repayments (principal and interest) data is more limited, but it also shows that Australian households have the highest debt servicing expenses among the countries assessed by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS):

The BIS data presented here is only up to the September quarter of 2022. As a result, it misses 1.75% of additional RBA rate hikes and the related increase in debt repayments.

Mortgage repayments will rise further:

Even if the RBA was to hold the official cash rate at 4.10%, this does not mean that average mortgage rates will stop climbing. Quite the contrary.

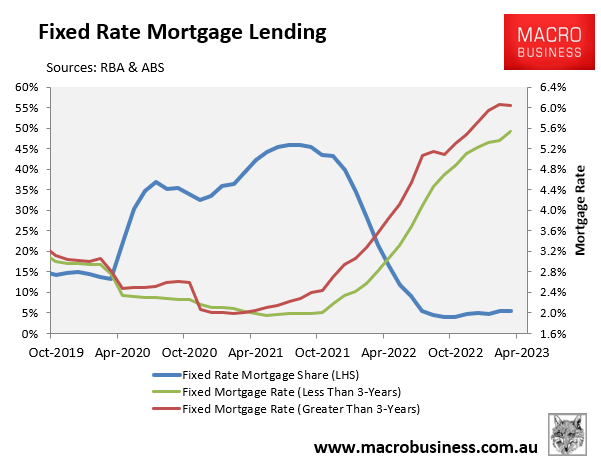

During the 18 months leading up to December 2022, nearly half of all borrowers took out fixed-rate mortgages, up from one-fifth prior to the pandemic:

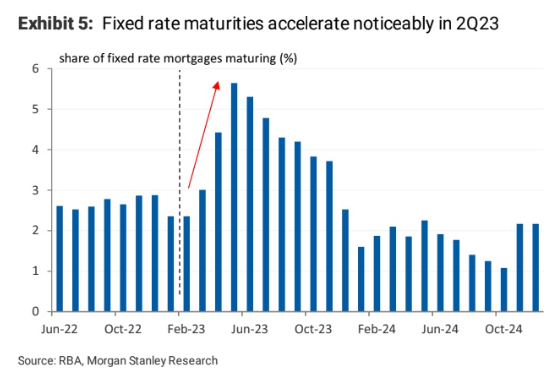

The majority of these mortgages are set to expire this year, causing borrowers to switch from ultra-low fixed rates of approximately 2% to variable rates of around 6%:

Around 500,000 fixed rate mortgages will expire over the remainder of this year alone.

As a result, even if the RBA does not raise interest rates further, average mortgage rates will continue to rise across Australia.

Indeed, Betashares chief economist David Bassanese told The Australian in April that “the higher-than-usual expiry of fixed-rate mortgages” will result in de facto policy tightening of at least 1.0%.

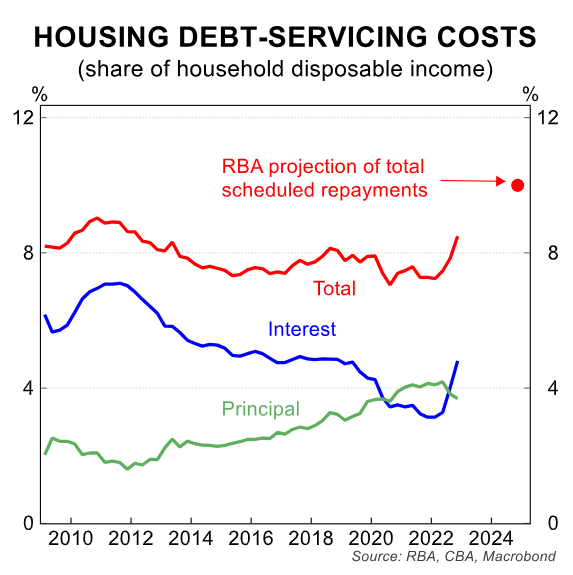

The following CBA chart depicts the impact of this fixed rate “mortgage cliff”, as well as recent rate rises:

It shows that scheduled mortgage repayments will lift to an all-time high share of household income in 2024.

Therefore, there is substantial tightening ‘built-in’ to Australia’s monetary settings owing to the expiry of fixed rate mortgages.

Australian households will soon be paying a record share of their incomes on loan repayments. And this will dwarf what mortgage holders abroad are paying.

That’s why Australia is the worst country in the world to be carrying a mortgage.