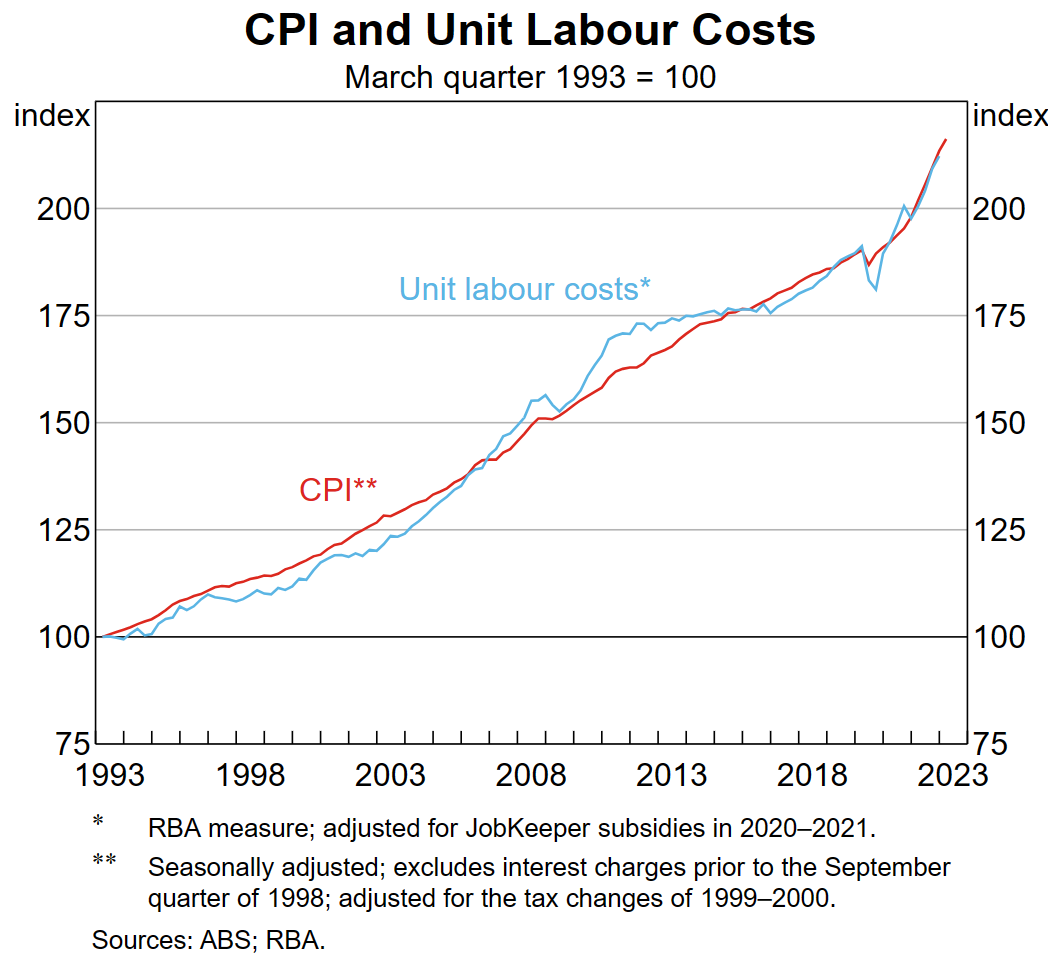

In an address this week at the Morgan Stanley 5th Australia Summit, RBA governor Phil Lowe produced the below chart comparing unit labour costs with the CPI in a bid to show how crucial wages are to inflation:

“Over the entire inflation targeting period, the cumulative increase in the CPI has closely matched that in unit labour costs, although there have been periods of divergence”, Lowe noted.

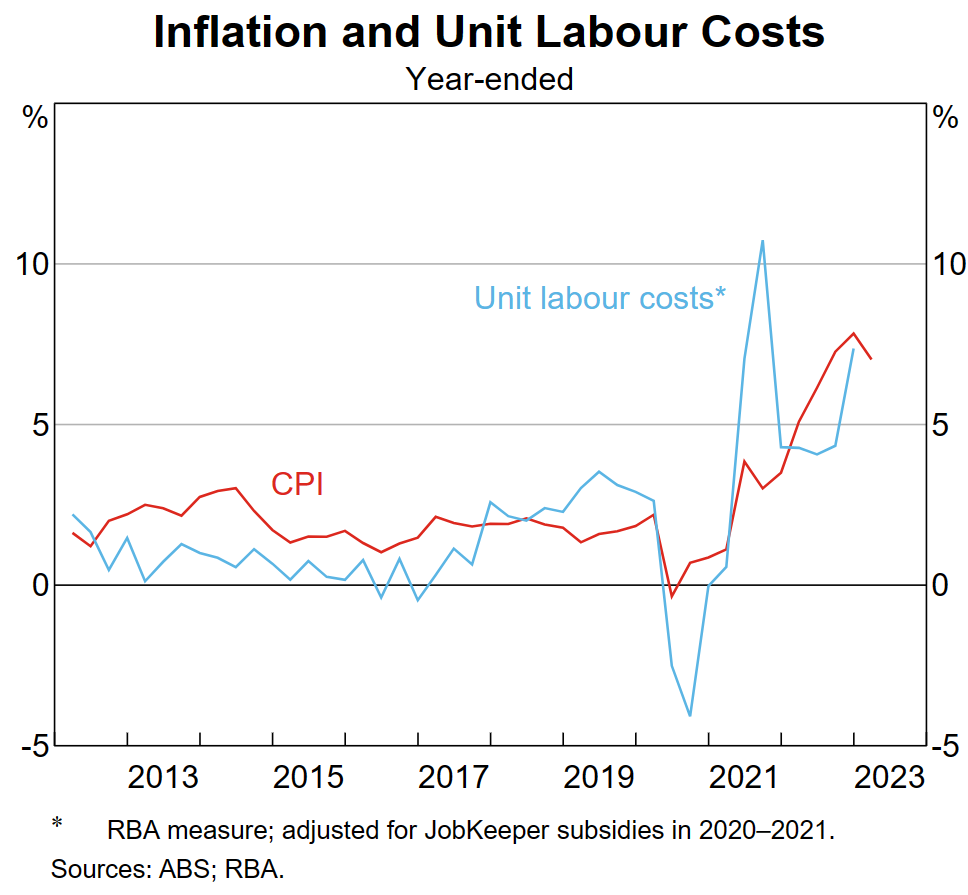

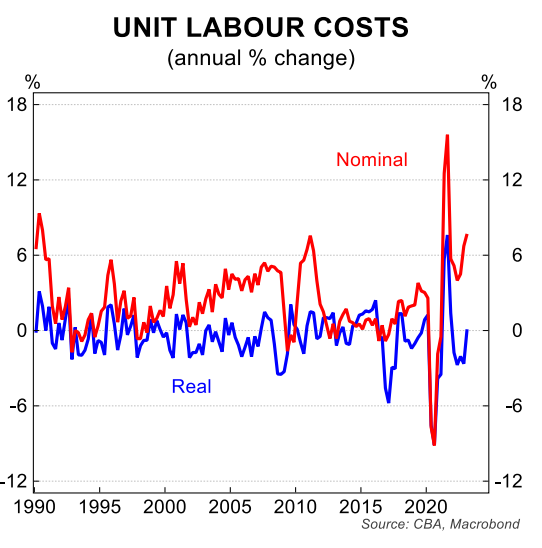

“In recent times, unit labour costs have been increasing quite strongly”:

“Over 2022, they increased by around 7.5%, which is one the largest annual increases during the inflation targeting period”.

“While the causation with inflation runs both ways, ongoing strong growth in unit labour costs would underpin ongoing high inflation outcomes”.

“The best way to achieve a moderation in growth in unit labour costs is through stronger productivity growth”.

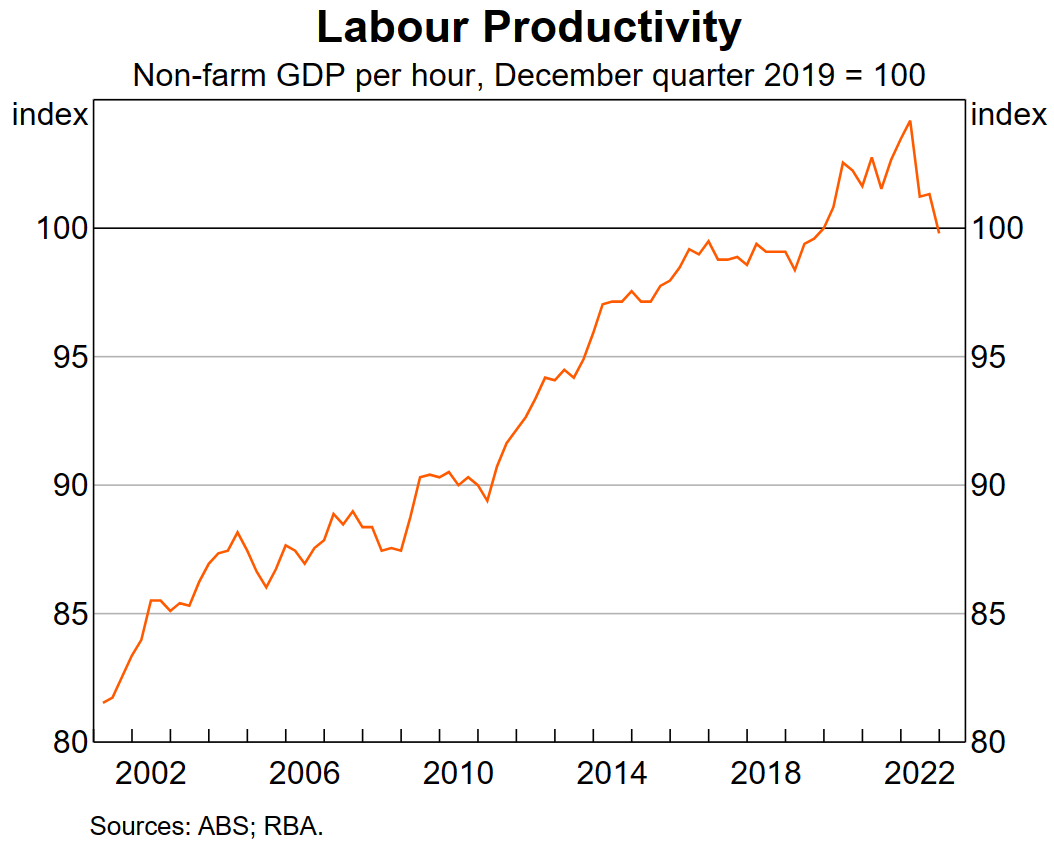

“Unfortunately, growth in productivity has been weak over recent times”:

“Indeed, the level of output per hour worked in Australia today is the same as it was in late 2019. This means there has been no net growth in productivity since then”, Lowe concluded.

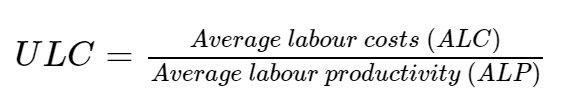

The formula used to measure Unit Labour Costs (ULC) is shown below:

According the ABS, ULC “are an indicator of the average cost of labour per unit of output produced in the economy” and “are a measure of the costs associated with the employment of labour, adjusted for labour productivity”.

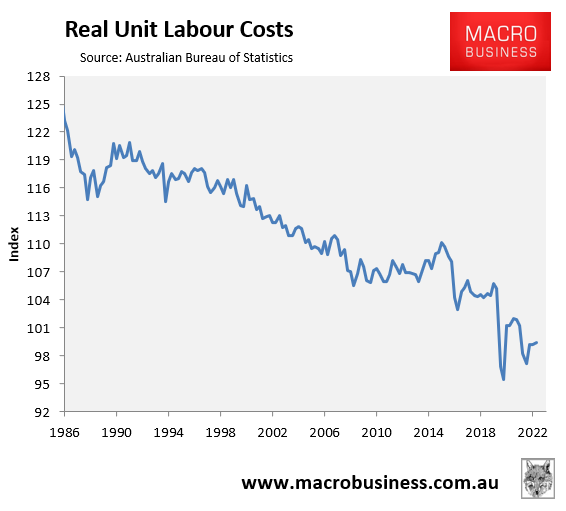

While its is disheartening that nominal ULC have risen 7.5% over the last year – similar to inflation – it is also important to note that real ULC, which “are an indicator of the direct labour cost pressures associated with the employment of labour, and exclude general price impacts”, are still running 6.0% below their pre-pandemic level:

Thus, the cost of labour for business has actually become cheaper over the pandemic.

The CBA has plotted both nominal and real ULC in the next chart:

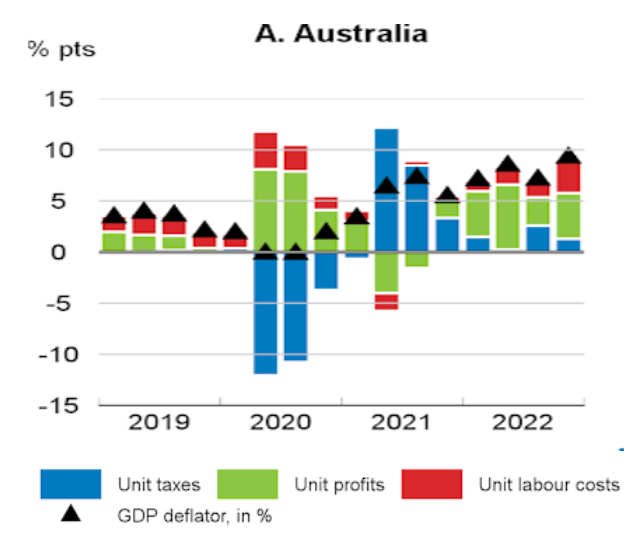

Research from the OECD released this week challenges the RBA’s assertion that rising labour costs are driving inflation.

“A significant part of the unit profits contribution has stemmed from profits in the energy and agriculture sectors, well above their share of the overall economy, but there have also been increases in profit contributions in manufacturing and services”, the OECD found.

Source: OECD

Over the last year, all major oil and gas corporations have recorded substantial profits.

Last year, Chevron’s profit more than doubled to $US36.5 billion, Shell’s profit doubled to $US40 billion, and Exxon’s profit soared to $US56 billion.

The OECD suggested one factor driving these increases could be a lack of competition, which allows enterprises to pass on expenses with relative impunity.

“A key policy issue is whether the observed aggregate increase in unit profits reflects a generalised lack of competitive pressures throughout the economy, or specific factors that have contributed to strong profit growth in a few sectors or in a subset of firms”.

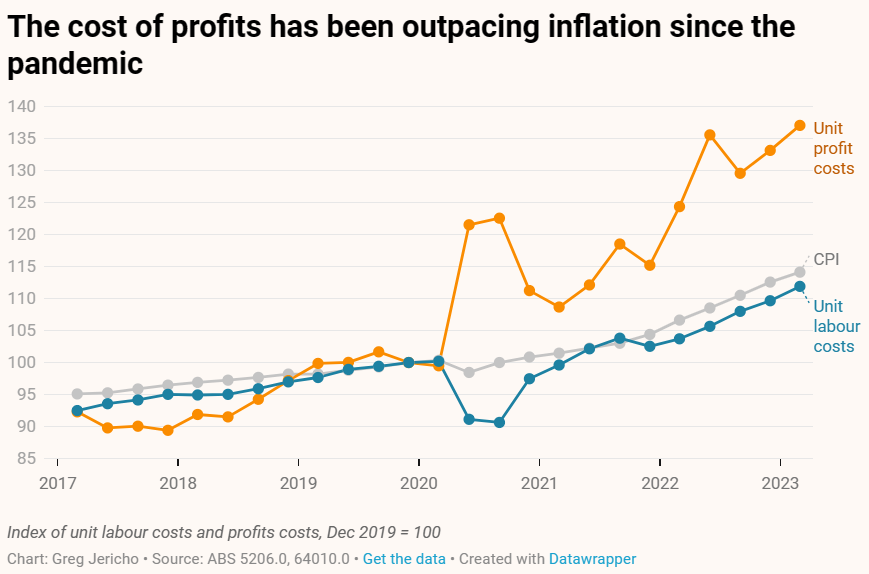

Greg Jericho from The Guardian and the Centre for Future Work has also questioned why the RBA has ignored the explosion in profits and their impact on inflation?

“Oddly he [Lowe] forgot to include the other main aspect of income in the economy – corporate profits. So I have done him a favour and reproduced the graph with them included”, Jericho wrote:

“Since the pandemic, unit profits costs have risen 37% while unit labour costs have risen 12%”.

“There will be a lot of commentary about rising labour costs meaning the RBA is going to have to increase rates again”.

“But can we just note that real unit labour costs – the labour cost of one unit of GDP – are now 6% lower than they were before the pandemic?”

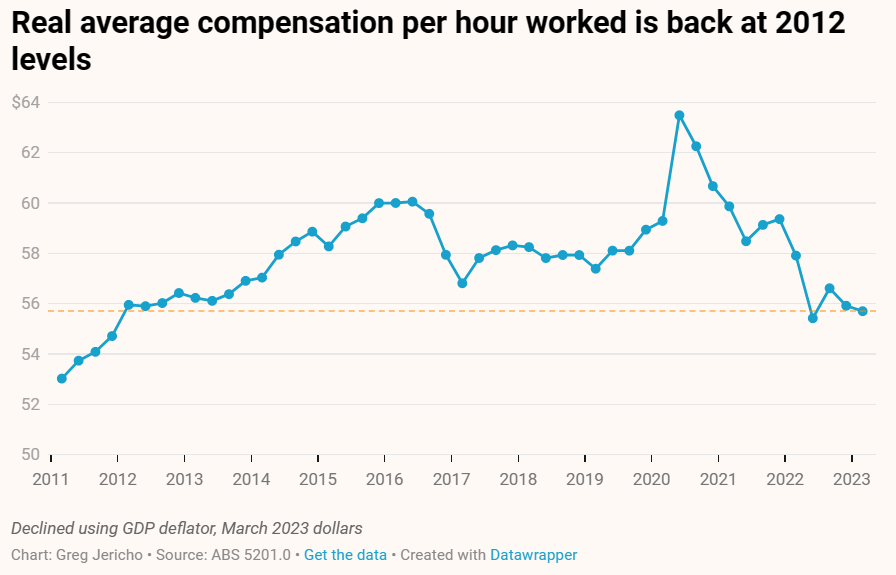

“The belief that labour costs must always fall in real terms is why households are doing it so tough, and why real compensation per hour barely grew in the decade before the pandemic and has plunged since then”:

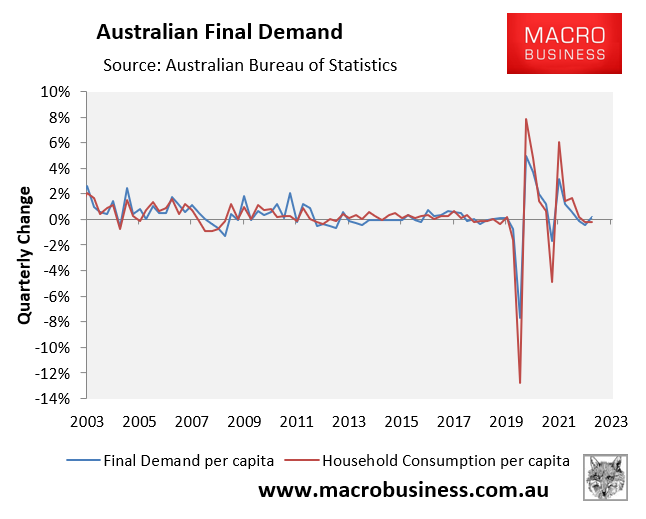

“Households are the economy… The impact of further interest rates will see household spending becoming ever weaker”.

Jericho’s not wrong: where household consumption goes, the economy typically follows:

In reality, it is profiteering by corporations boosting prices to fatten their margins that is driving Australia’s inflation, not workers, who are seeing the fastest decline in real wages on record.

The above analysis also shows, yet again, why the Albanese Government must take a more active role in lowering inflation by intervening directly in the energy market to smash the gas cartel and lower energy prices.

The Albanese Government should also lower immigration to a level commensurate with the growth in business investment, infrastructure and housing supply.

Otherwise, Australia’s capital stock will continue to shallow and rents will soar, wrecking productivity growth and stoking inflation.

The least the RBA can do is be honest about the situation, stop blaming workers, and tell the Albanese Government to do its job and lower inflation.