The AFR has been pumping articles all week blaming Australia’s housing shortage on a lack of supply and NIMBYism, to the joy of the property development lobby.

Their propaganda has been praised by the likes of economist Matt Cowgill – a guy that continually defends the ‘Big Australia’ mass immigration policy, while blaming Australia’s housing shortage on NIMBYism and a ‘lack of supply’.

This week on Twitter, Cowgill hailed former RBA economist Tony Richards’ debunked research, which pinned Australia’s housing shortage on a failure to build enough homes:

Then Cowgill hailed Auckland for ‘taking on the NIMBYs’, which has supposedly created an affordable housing market:

Michael Read’s actual article on Auckland calls on Australia to emulate Auckland’s upzoning reforms.

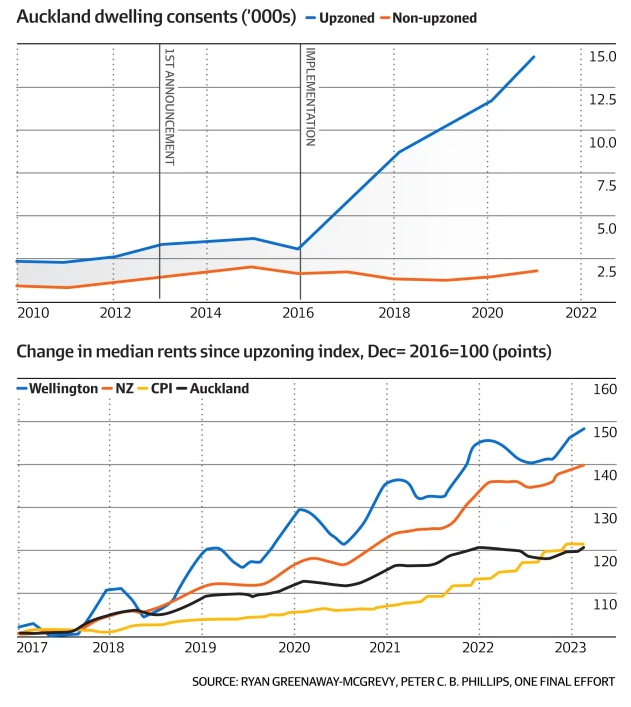

“A radical move in 2016 to liberalise zoning laws in New Zealand’s largest city ushered in a building boom that has spared the region from the big increase in house prices and rents across the rest of the country”, argues Read.

“It could also be a blueprint for Australia, where restrictive planning laws have been blamed for a shortage of rental accommodation and high house prices”.

“Overall, about 75% of Auckland’s residential land was upzoned as a result of the plan, tripling the city’s dwelling capacity”.

“The increase in supply has kept a lid on rents and house prices”.

“Since 2016, rents have increased 10% to 20% in Auckland, compared with about 40 per cent in Wellington. House prices are about 20% higher, compared with the 70% lift that occurred outside Auckland”.

“Dr Greenaway-McGrevy said Auckland’s successful zoning reform was a blueprint for other cities”.

I spell something fishy.

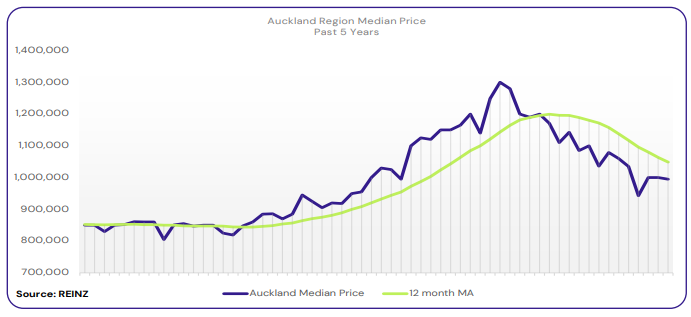

Auckland is renowned for having one of the world’s most expensive housing markets.

Prices skyrocketed in the years leading up to the pandemic to a median of $1.3 million, only to then crash once the Reserve Bank aggressively hiked interest rates from October 2021 (Wellington’s prices also crashed):

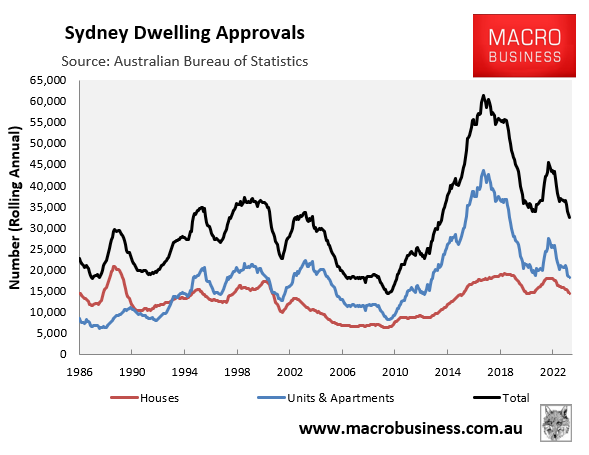

Another interesting point to note is that Auckland has merely emulated what Sydney already did since the 1990s, as reported in The SMH last year.

“Professor Nicole Gurran, an urban planning expert at the University of Sydney, says much of what Auckland and New Zealand are doing now has happened in Sydney since the 1990s”.

“Over time, the government has tried to strip councils of their power over development consent by creating local and regional planning panels independent of council, rezoning land near train lines and sometimes taking direct control of developments and precincts”.

Indeed, Sydney experienced a massive uplift in high-rise dwelling approvals (consents) last decade:

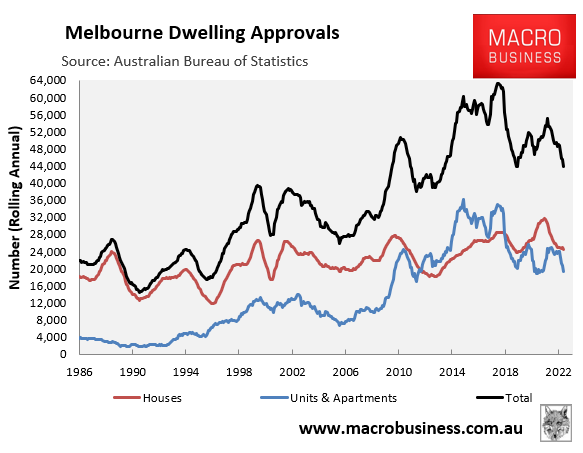

So did Melbourne:

So did the combined capital cities:

Yet, Australia’s housing affordability continued to worsen.

The supply-siders’ inference is that Australia is somehow bad at building homes.

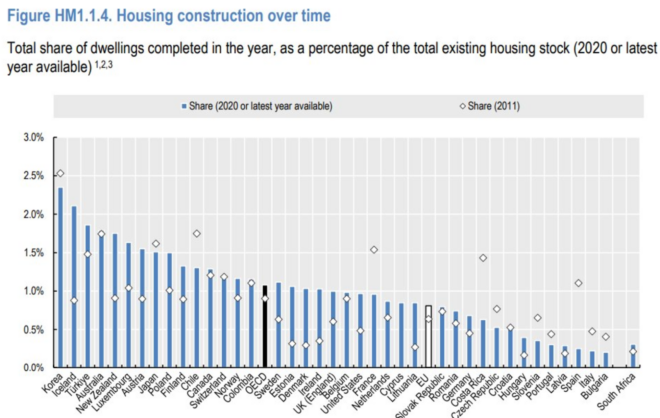

Yet the OECD’s Affordable Housing Database shows that Australia has built significantly more dwellings per capita than most other OECD countries:

Australia ranked fourth in the OECD for housing construction rates in 2020.

Australia’s dwelling construction rate was also unchanged from 2011, according to the OECD.

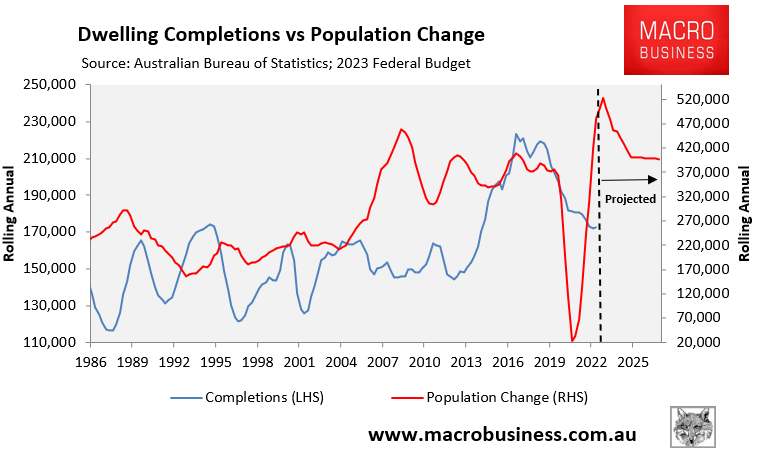

The reality of the situation is highlighted in the below chart comparing dwelling completions to actual and projected population increase as outlined in the Federal Budget:

Again, Australia’s rate of dwelling construction surged in the 2010s.

However, this construction boom was not enough to keep pace with the massive increase in immigration-driven population growth from the mid-2000s, which is projected to hit new heights going forward.

Instead of waxing lyrical about an imaginary ‘lack of supply’, why not point the finger at ‘too much demand’ caused by Australia’s extreme immigration policy?

Growing Australia’s population by between 400,000 and 500,000 people a year, as projected in the federal budget, necessarily means Australia’s housing shortages will worsen, resulting in higher rents and increasing homelessness.

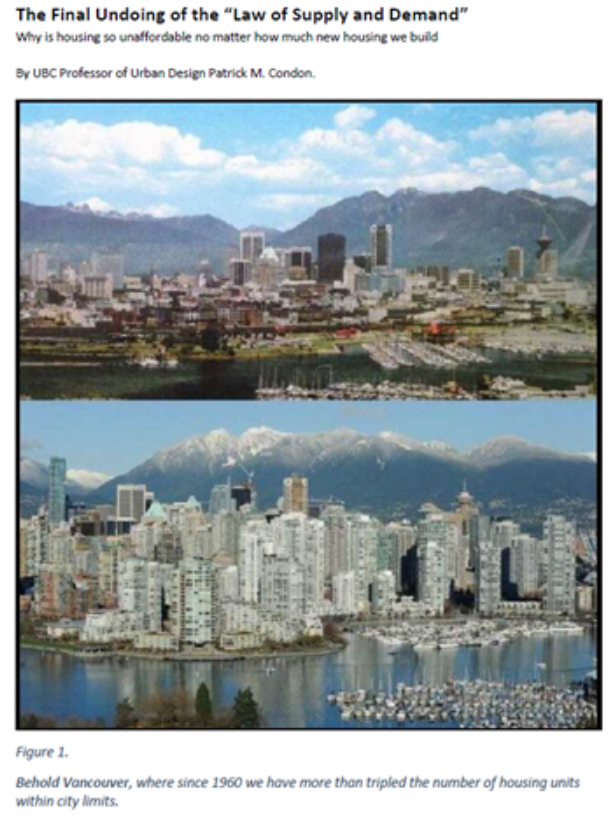

Besides, if the solution to housing affordability was to simply upzone and build loads of apartments, why hasn’t it worked for Vancouver – one of the world’s most expensive housing markets?

As Patrick Condon (James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC Urban Design program) points out, Vancouver tripled its housing via high density infill:

“This was an unreservedly good thing – in all but one respect. This giant surge of new housing supply did not lead to more affordable housing as we all hoped. Somehow, confoundingly, the reverse happened.”

Sure did. Vancouver became Canada’s least affordable housing market in terms of prices, as well as one of the least affordable housing markets in the world.

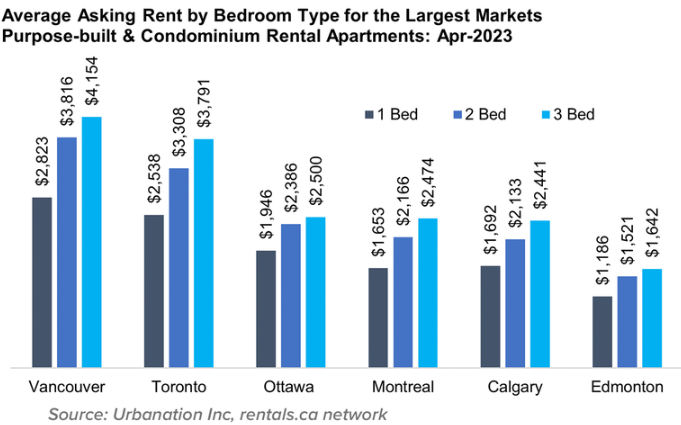

Vancouver’s rents are also the highest in Canada by a long-shot:

Not a great outcome if affordability is your objective. Don’t be like Vancouver.

It’s no coincidence that Vancouver, like Sydney and Melbourne, has also been flooded with overseas migrants.

The fact of the matter is that Australia will never build enough homes so long as its population continues to grow like a science experiment via extreme levels of immigration.

We didn’t build enough homes in the 15 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration leading up to the pandemic. And we certainly won’t under the record immigration deluge projected by the Federal Budget.

If commentators like Matt Cowgill and his ilk genuinely cared about ending the nation’s housing shortage, they would argue for an immigration program that is substantially lower than the nation’s ability to supply homes, not the other way around.

It is time to stop scapegoating a ‘lack of supply’ and start addressing the immigration elephant.