Gareth Aird at the CBA with the dour news.

We forecast GDP growth to be 0.7%/yr at Q4 23 and 1.9%/yr at Q4 24.

Broadly flat real household consumption over the remainder of 2023 sits at the heart of our forecasts for the economy to grow significantly below trend and be in a per-capita recession for the remainder of this year.

We put the odds of a recession in 2023 at 50% as the lagged impact of the RBA’s rate increases continues to drain the cash flow of households that carry debt.

We expect the annual rate of inflation to decline to 3.8% by late 2023 (our forecast is for underlying inflation to be 3.6%/yr in Q4 23).

We expect the unemployment rate to grind higher over 2023 to end the year at 4.4% and to be 4.7% by mid-2024.

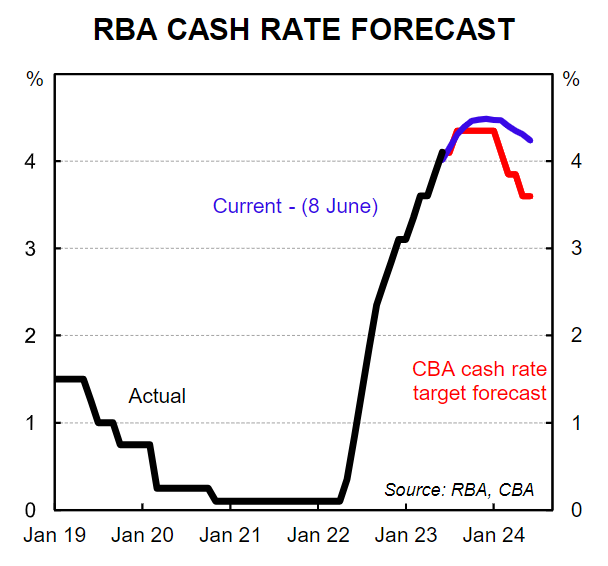

Our economic forecasts are conditional on one final 25bp increase in the cash rate in Q3 23 for a peak this cycle of 4.35%. They are also conditionalon125bp of policy easing in 2024.

Monetary policy is now deeply restrictive, which means by definition the economy will slow materially from here.

We downgrade our economic forecasts following the change of RBA call

Earlier this week we updated our RBA call in light of the 25bp rate hike at the June Board meeting, RBA Governor Lowe’s speech today and the Q1 23 national accounts.

We now expect one further 25bp increase in the cash rate for a peak of 4.35% and see it most likely at the August Board meeting. The risk is a 25bp rate hike earlier in July. There is also a risk of 25bp rate rises in both July and August, which would take the cash rate to 4.6%.

We also pushed out the timing of the start of rate cuts from Q4 23 to Q1 24 – we expect 125bp of easing in 2024 (50bp of rate cuts in Q1 24 and 25bp of easing in each of Q2 24, Q3 24 and Q4 24, which would take the cash rate to 3.10% at end 2024).

Our updated RBA call means that we have downgraded our assessment of the economic outlook.

Tighter monetary policy means weaker economic growth

Previously we expected GDP growth to slow to 0.9%/yr in Q4 23. That forecast was conditional on a peak in the cash rate of 3.85%.

As a result of our change in RBA call we have downgraded our forecast for GDP growth to 0.7%/yr in Q4 23.

With annual population growth expected to be ~2.0% in 2023, we expect Australia to be in a per‑capita recession over the year.

Household consumption grew by just 0.2% in Q1 23. But the detail highlighted the current tough period for many households.

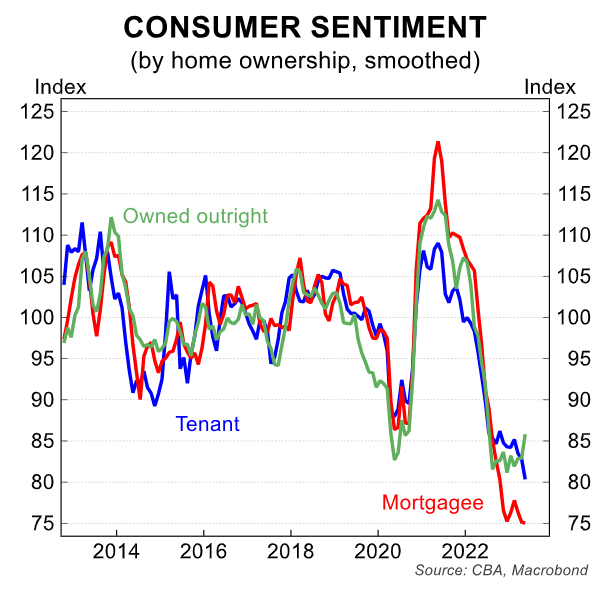

Growth in essential spending increased over the quarter (1.1%), while discretionary spending fell by 1.0%. It is no wonder consumer sentiment is sitting in the doldrums. We expect consumer sentiment, as measured by the Westpac/MI survey, to sink further in June when the data is published next week (13/6).

Our expectation is that real household consumption is essentially flat over the rest of 2023. Against a backdrop of 2.0%/yr population growth that implies a solid negative fall in consumption per capita. Indeed it would not surprise us to see a quarter or two of negative growth in total household consumption.

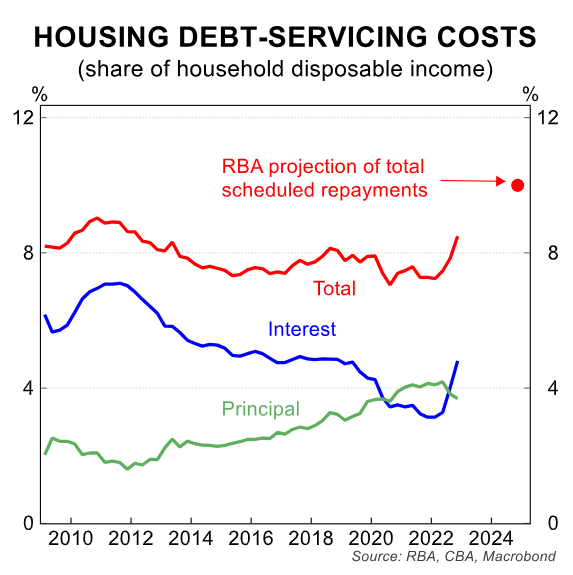

Monetary policy works with a lag. Only around half of the RBA’s already delivered 400bps of policy tightening have hit the household sector. As the lagged impact of rate rises continues to hit home borrowers mortgage repayments will rise to a record high as a share of household income (see facing chart). This will have a negative impact on household consumption.

Nominal income growth will continue to be supported by wages growth, which we expect will lift to 3.9%/yr in Q3 23. But this will not be enough to offset the ongoing drag on the consumer from rising mortgage repayments.

An expectation that rental inflation will continue to lift will also hit the large number of households that rent. While rents are effectively a transfer payment within the household sector, many investors will be faced with higher mortgage repayments. So a good chunk of the money transferred from tenants to landlords will exit the household sector (note that the Government also taxes rent as it is considered income to the landlord).

What about the savings?

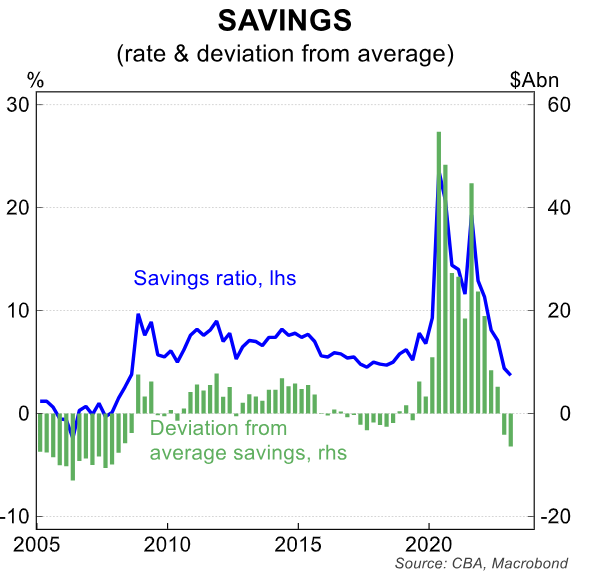

A large stock of savings were accrued during the pandemic. But the savings were not distributed evenly. As the facing chart shows, the bulk of the savings amassed during the pandemic sit within the older cohort of society.

We do not expect this demographic to draw down on their savings swiftly. Rather they are likely to spend these savings in a protracted way over many years. The upshot is that we do not anticipate a speedy injection of the accrued savings back into the economy.

Households as a collective tend to draw down on savings when they are feeling positive about the economic outlook. That is not the case right now. The anxiety being felt in the household sector as a whole is showing up in very weak readings of consumer sentiment – historically consistent with a major negative economic shock or recession.

The savings rate fell to a below‑average 3.7% in Q1 23. It can fall further. Based on our forecast profile for household consumption and household disposable income, we expect the savings rate will hit a floor of ~2.5% in H2 23.

Weaker growth means higher unemployment

Our downgraded assessment of economic growth means we mechanically upwardly revise our forecast for the unemployment rate. We see the unemployment rate increasing to 4.4% by end‑2023.

It is likely that measured productivity growth will stay weak over coming quarters as there is a lag between slowing economic activity and rising unemployment.

Initially firms will keep workers on the books as demand slows. This weighs on measured output per hour worked. Output (i.e. production) slows faster than the demand for inputs (i.e. labour). So productivity remains weak and unit labour costs stay elevated for a period of time. But this dynamic does not last indefinitely.

Once demand has slowed for a sufficient period of time some firms will respond by decreasing the hours they require their staff to work. A reduction in headcount also occurs. This is expected to happen in the discretionary parts of the economy where spending is forecast to contract. These outcomes are being engineered by restrictive monetary policy in order to drop the rate of inflation.

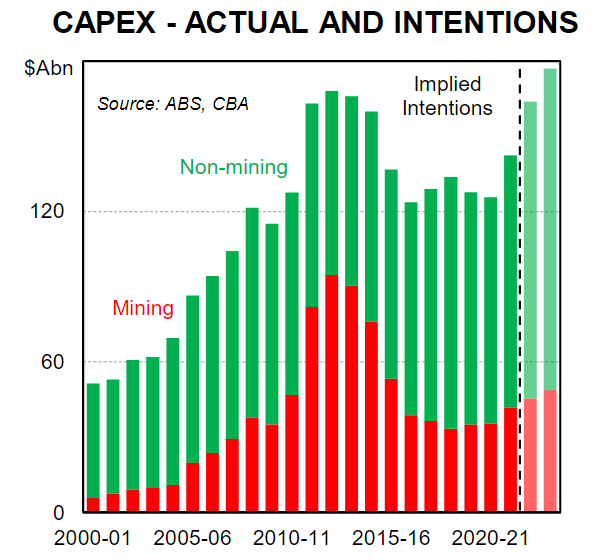

Business investment still looks good

The most recent capex survey was a decent one. Investment intentions were firmer than we anticipated. But not all strong data is bad data just because the objective is to drop inflation. Indeed firmer capex plans should be welcomed.

Business investment lifts capital deepening (where the capital per worker is increasing in the economy). This improves productivity (output per hour worked). There has been a lot of focus lately on weak productivity in the economy. So firming capex intentions are good. The RBA wants to see productivity rise. And higher investment is an ingredient required to lift productivity. In the long run business investment is disinflationary as the productive side of the economy is expanding. It also makes sense to have a decent investment outlook given annual population growth is 2%.

Our home price call is unchanged

According to CoreLogic, Australian property prices rose for a third consecutive month in May. The 1.4% increase in the 8 capital city benchmark index over the month followed a 0.7% increase in April and a 0.8% lift in March.

The turnaround in property prices over the last three months has been nothing short of remarkable given the RBA has continued to lift the cash rate over that period.

In April we upgraded our home price forecasts. Our point forecast is for home prices to lift by 3% in 2023 and a further 5% rise in 2024. We have not changed this forecast despite the change in our RBA call.

The RBA recently cited home prices as feeding into their decision to lift the cash rate “services price inflation is proving persistent here and overseas, and the recent data on inflation, wages and housing prices were higher than had been factored into the forecasts. Given this shift in risks and the already fairly drawn‑out return of inflation to target, the Board judged that a further increase in interest rates was warranted.” (our emphasis in bold).

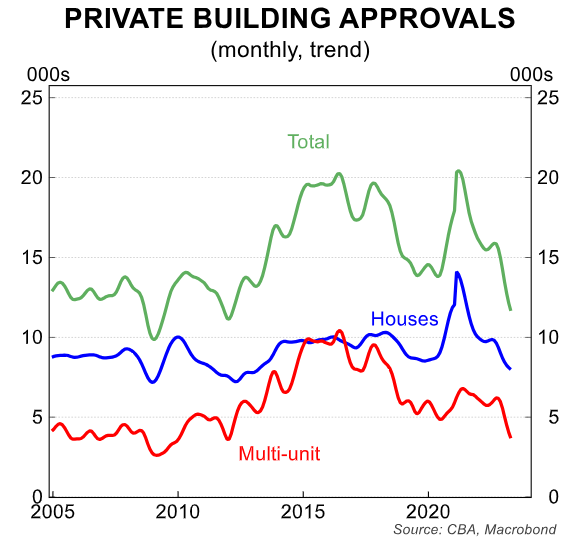

But the RBA is facing an uphill battle to change the outlook for home prices by lifting the cash rate as monetary policy tightening is behind the big drop in building approvals.

Further rate hikes reduce borrower capacity, which should by itself put downward pressure on home prices. But rate hikes also decrease the rate at which new homes will be built. This further exacerbates the mismatch between the underlying demand for housing and supply. The circularity here means we do not think our change of RBA call for a higher terminal rate alters the outlook for home prices.

There is light at the end of the tunnel

Readers may feel like there is a pessimistic tone to this note. That is understandable. Economists don’t take pleasure in downgrading the outlook for economic growth and upwardly revising their forecasts for unemployment. But there is light at the end of the tunnel.

Once the proverbial ‘inflation dragon’ is slayed monetary policy will be able to move away from a deeply restrictive setting to a more neutral one. Rate relief will arrive to the household sector in the future and we expect that to happen in early 2024.

As interest rates are cut it will free up cash for those borrowers that have a mortgage. And the demand for credit will begin to lift. As this happens economic momentum will start to pick up and the upward trend in the unemployment rate will wane. Consumer sentiment and spending will lift.

Our expectation is that the unemployment rate will peak at 4.7% in mid‑2024 before grinding back down to 4.5% in late‑2024. This is below the pre‑pandemic level of ~5.0%.

Ultimately we will not be able to hold onto all of the gains we made in employment over the pandemic. And the RBA readily acknowledges this as they see some lift in the unemployment rate as a necessary condition to return inflation to target.

But if we end up with inflation back to target, unemployment at ~4.5% and wages growth at ~3.5% by the end of 2024 then Australia will have done a lot better over the period ahead than many other economies.

There are risks of course in both directions. And the economic data coupled with the decisions of the RBA Board over coming months will give us a better sense of the balance of these risks.