NAB CEO Ross McEwan told the parliament’s House of Representatives economics committee on Wednesday that without immediate action to increase housing supply, surging overseas migration will put even more upward pressure on house prices and rents.

McEwan warned there is a “chronic undersupply” of homes, which will collide with the nation’s rapidly expanding population, forcing up prices in an already “pretty pressured system at the moment”.

“We need to get more land available for the building of houses very quickly” and “fast-tracking planning permissions and development would be the single most effective way” to alleviate pressures, he argued.

“A co-ordinated effort by state and territory governments to introduce faster, simpler and more consistent processes for approving land development and residential construction will lift supply”.

“We need to get building houses”, he said before attacking so-called NIMBYism.

Like most commentators, McEwan has correctly identified the problem but not the solution.

The main cause of the nation’s housing shortage is the federal government’s reckless mass immigration policy.

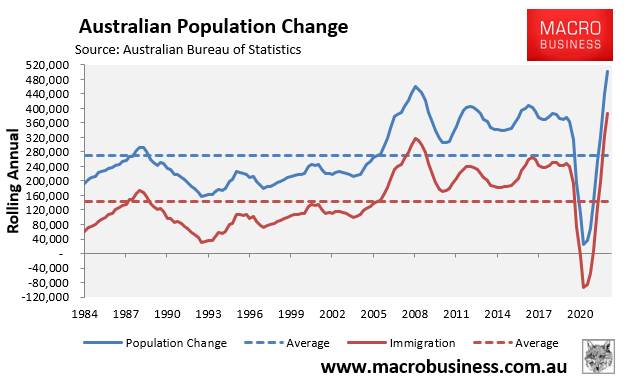

Australia’s population ballooned by an unprecedented 497,000 people in the 2022 calendar year, off record net overseas migration (NOM) of 387,000:

This meant that Australia’s population grew by 1,361 people per day last calendar year, driven by NOM of 1,060 people per day.

In Australia, the current population density per dwelling is roughly 2.5.

Dividing this daily population/NOM increase by this figure gives an estimate of how many dwellings need to be added to Australia’s housing stock to accommodate the nation’s population growth.

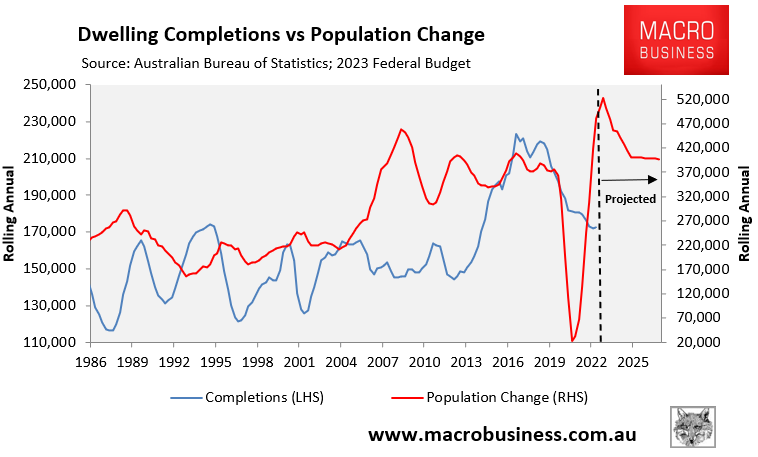

Last year, Australia needed to build 544 new homes a day to accommodate the additional population, with 424 of these new dwellings dedicated only to new migrants.

Instead, Australia added just 154,400 dwellings to its housing supply in 2022, amounting to 423 dwellings per day.

According to the May federal budget, Australia’s population will grow by 2.18 million people over the five years to 2026-27, with NOM accounting for 1.5 million of this increase.

That is the equivalent to adding a Perth’s worth of population in only five years, with an Adelaide’s worth coming purely via NOM.

This means that Australia will add 1,194 people every day over the five years to 2026-27, with NOM accounting for 822 of this increase.

Using the 2.5 people per dwelling ratio, this means that Australia will need to add 478 homes each day, with 329 of these dwellings required solely for new migrants.

Australia will also need to build more than this number of dwellings to account for demolitions.

Given actual building rates have declined due to widespread builder insolvencies and skyrocketing material and financing costs, the chance of meeting these house supply targets is zero:

Indeed, Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy told a Senate Estimates hearing in late May that the housing construction downturn will run until 2025, with investment in new dwellings projected to fall by 2.5% this year, 3.5% in 2023-24, and 1.5% in 2024-25.

Oxford Economics Australia likewise forecast that total housing construction work would fall by a cumulative 21% over the three years to financial year 2025.

Let’s also not forget that thousands of projects have been delayed or cancelled amid soaring costs, which shows that it is not a planning issue but a cost issue.

In short, the Albanese Government’s reckless mass immigration policy means that Australia’s housing shortages will continue to worsen, driving up rents and forcing thousands of Australians into homelessness.

The number one solution to the problem is to reduce net overseas migration to levels in line with the nation’s ability to supply housing, infrastructure and services.

Net overseas migration should be lowered to historical levels of around 100,000 people a year.