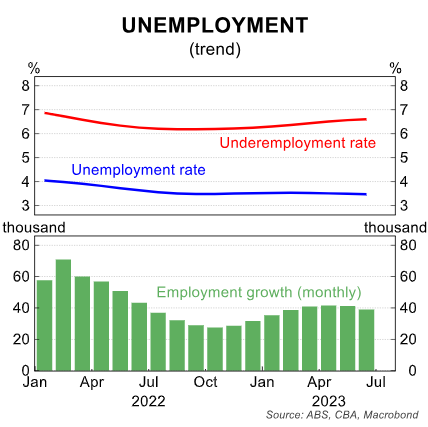

Last week, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) revealed that Australia’s trend unemployment rate remained steady at 3.5%, despite a swag of leading indicators showing a weakening labour market.

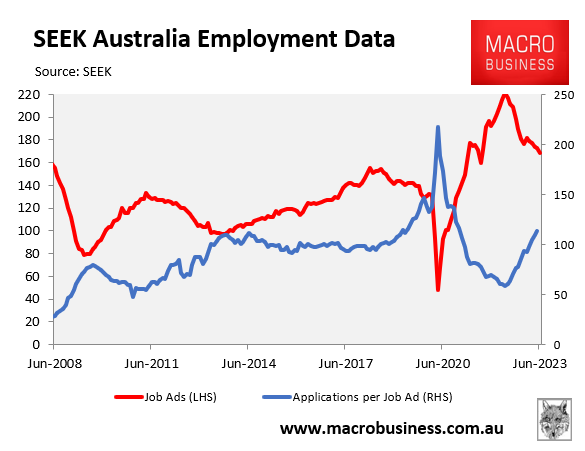

First, job ads across various measures are elevated but easing, which is evidence of softening labour demand:

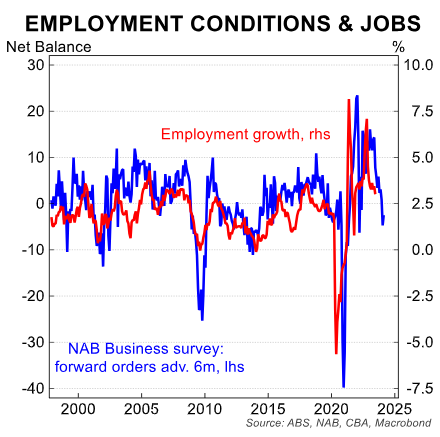

Second, business and consumer surveys with key sub-categories correlated with labour market outcomes are also softening.

This includes forward orders in the NAB business survey:

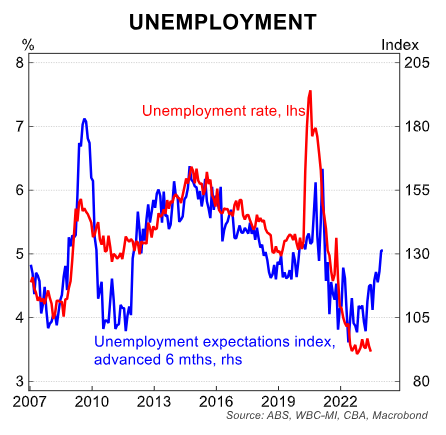

Unemployment expectations in the Westpac-Melbourne Institute consumer sentiment release are also pointing to rising jobless:

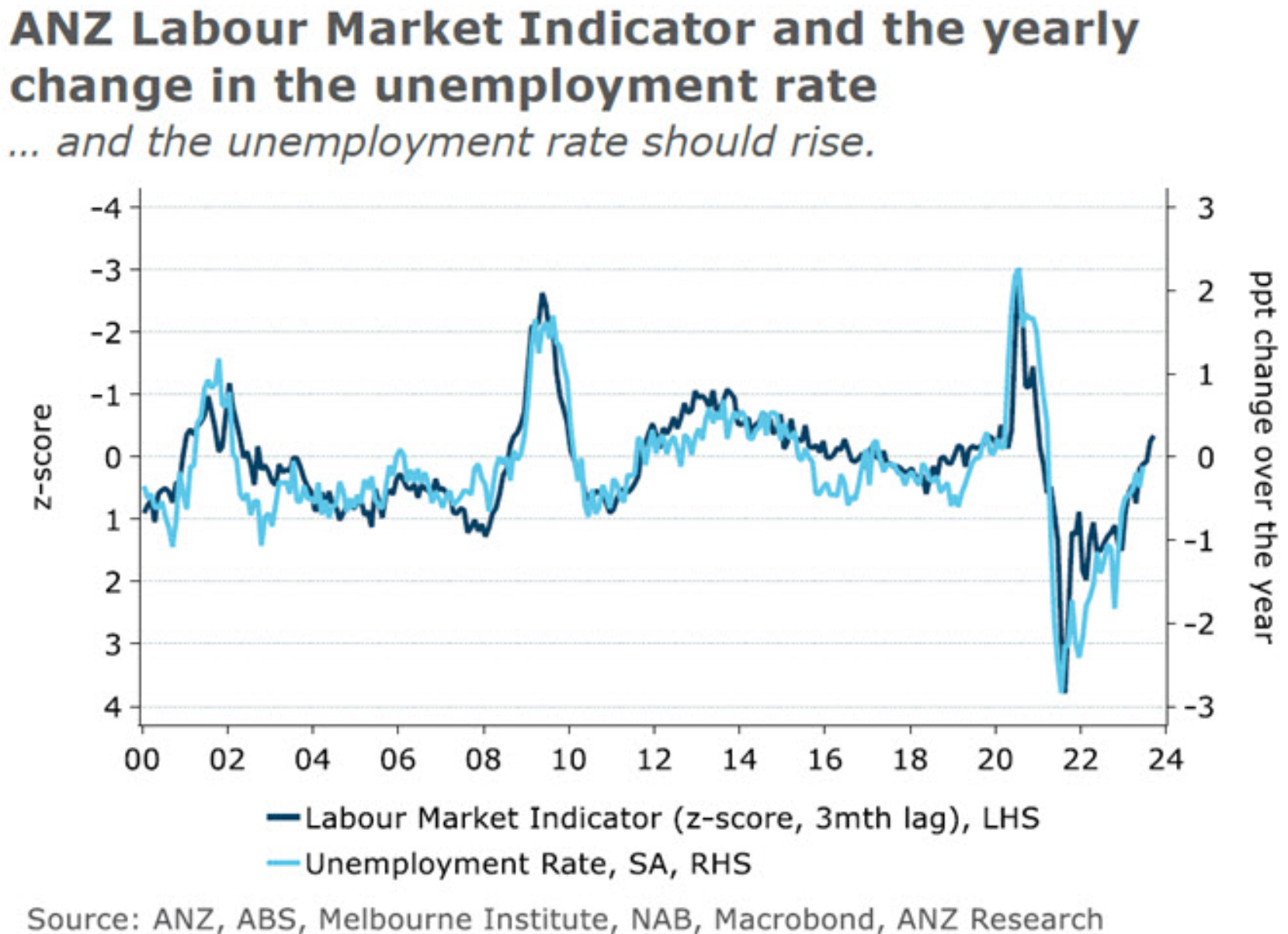

As does ANZ’s Labour Market Indicator:

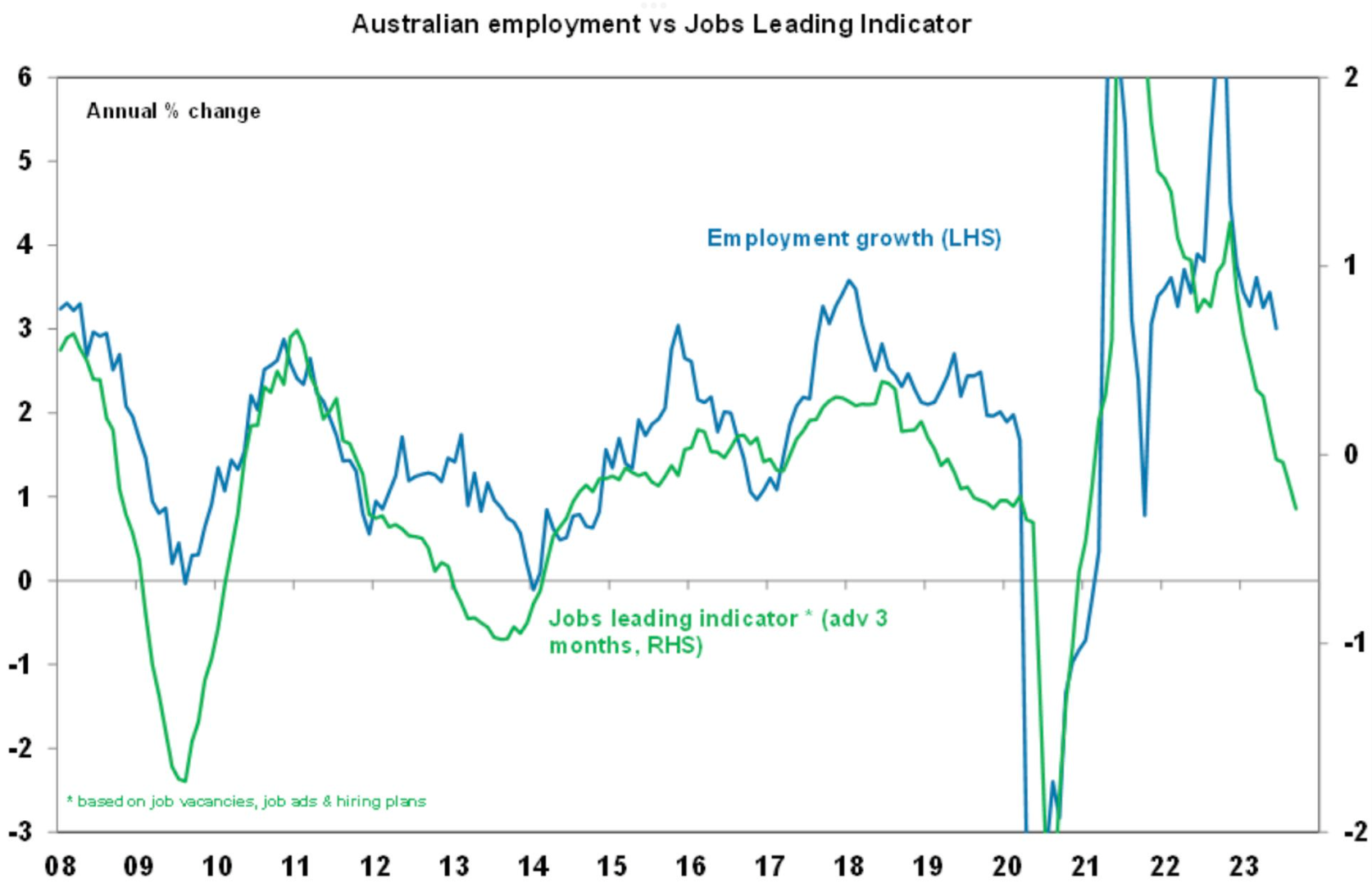

And AMP’s jobs leading indicator:

The number of job applications per vacancy has returned to pre-pandemic levels:

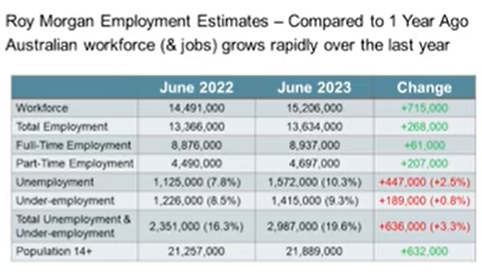

Finally, Roy Morgan’s unofficial labour market survey showed rising unemployment year-on-year in June as jobs growth failed to keep pace with record immigration-induced labour supply growth:

Over the weekend, business reporter Gareth Hutchens published an interesting article that helps to explain why Australia’s unemployment rate has remained low in the face of record labour supply growth and a softening economy.

TLDR: Australia’s huge backlog of job vacancies accumulated over the pandemic has meant that new migrants are filling unfilled jobs. And the unemployment rate could remain low until job vacancy levels return to ‘normal’.

Below are the essential extracts from Hutchens’ article, which builds on recent analysis from Professor Jeff Borland:

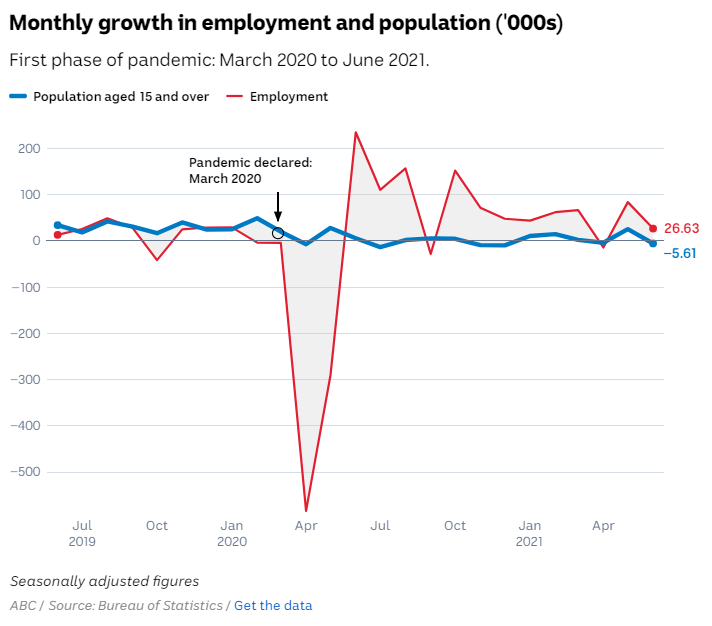

“Monthly population growth suddenly turned negative in April 2020, and it was frequently negative through to August 2021”, notes Hutchens.

“That occurred because our international border was closed in that period and foreign students and other migrants left Australia to return home”.

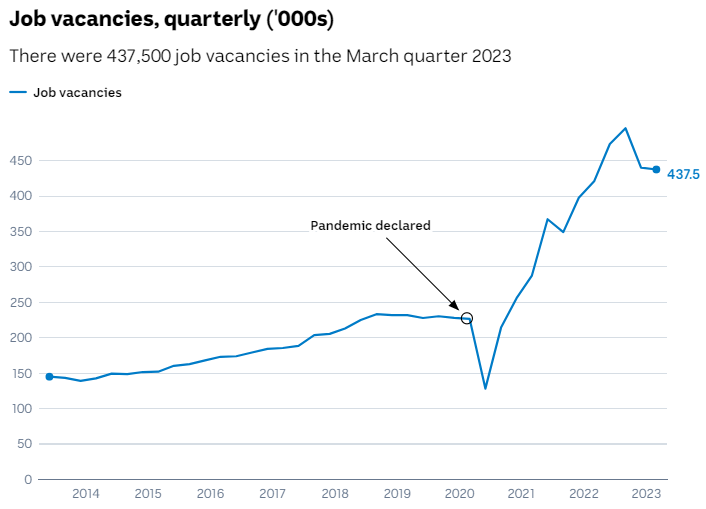

“With so many people leaving the country abruptly, the number of job vacancies started to shoot skywards”:

“When the first lockdowns ended and economic activity picked up again, those vacant jobs could only be filled by people living here (because the international border was still closed)”.

“Employment grew by 78,045 people a month, on average, between June 2020 and June 2021, while the population only grew by 2,216 people a month (thanks to natural increase from births)”:

“With the population growing so slowly in that early closed borders era, employers could only achieve that level of employment growth by sourcing workers from the local pool of unemployed people, and from people on the margins of the labour force”.

“It saw the unemployment rate fall rapidly from 7.4% in June 2020 to 5% in June 2021”.

“Employment still grew much faster than the population for the next six months after that (over the first half of 2022)”.

“It caused the unemployment rate to fall even further, from 5.3% in October 2021 to 3.5% in July 2022”.

“Since that transition point in mid-2022, the unemployment rate has been averaging 3.5 per cent, but labour market dynamics have been changing”.

“Not only has the pace of employment been slowing since that point, but employment growth has been coming almost entirely from population growth (i.e. increased immigration)”.

“The reason why the unemployment rate hasn’t been increasing from 3.5% is because we still have a near-record level of job vacancies”.

“Fewer new jobs are being created, but an unusually high number of vacancies is keeping demand for workers high”.

“New entrants to the labour force have been able to take up those vacancies, rather than becoming unemployed”.

“Notice how, in the graph of job vacancies earlier in the piece, the number of job vacancies peaked in the September quarter last year and has been falling slowly since then”.

“So, how long can the unemployment rate stay near 3.5%?”

“Continued (now modest) growth in new job creation, together with the huge backlog of vacancies, might well allow the rate of unemployment to remain around its current level — even with a high rate of population growth”.

This analysis makes sense and has parallels to the housing market, where a huge pipeline of unfinished homes is keeping builders busy despite the crash in approvals, new home sales, and construction finance commitments.

The unemployment rate will shoot up once the pipeline of job vacancies is exhausted.