Prime Minister Anthony Albanese emerged from Wednesday’s National Cabinet Meeting with a ‘bold’ plan to fix Australia’s housing crisis.

Albo and the state’s premiers agreed to build 1.2 million new homes over five years from 1 July 2024.

This plan was a 20% increase on the one million National Housing Accord target agreed by states and territories last year.

To encourage the states to achieve this target, the Albanese Government has committed to $3 billion for performance-based funding, the New Home Bonus.

States and territories that achieve more than their share of the one million home target under the National Housing Accord will be eligible for $15,000 of extra funding per home.

National Cabinet also agreed to a National Planning Reform Blueprint, which will seek to build medium and high-density apartments in established middle-ring suburbs.

While the 1.2 million homes target is a flashy announceable, it raises a bunch of issues.

First, how can Australia realistically meet this supply target given the building industry is on its knees suffering from materials and labour shortages, soaring cost inflation, and widespread insolvency?

In May, Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy told the Senate Estimates Economics Committee that investment in new homes is forecast to fall by 2.5% in 2022-23, 3.5% in 2023-24, and by 1.5% in 2024-25.

Similarly, Oxford Economics Australia forecast that overall dwelling construction activity would shrink by 21% over the three years to 2024-25.

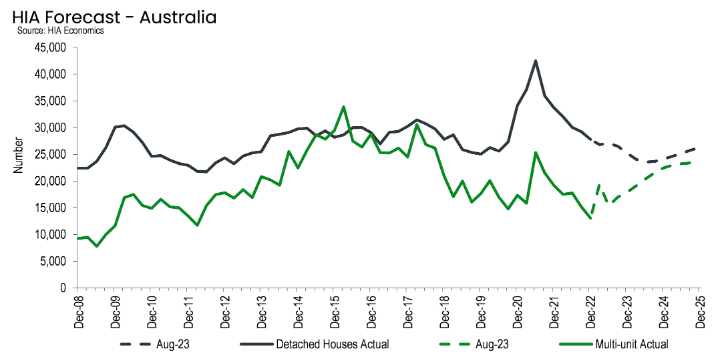

The Housing Industry Association this week forecast heavy falls in new home construction over coming years:

“Even if the RBA were to cut rates today, detached home building activity is set to slow to its lowest levels in more than a decade”, warned HIA’s Chief Economist, Tim Reardon.

“Despite this need to increase housing stock, the number of new homes commencing construction is set to stagnate”.

CBA economics also forecast heavy falls in housing starts.

Second, the $3 billion of incentive payments to the states are back ended and would only be received in 2029.

Thus, the states would somehow have to fund the development upfront in the hope that they can receive payment way down the track, and only if they can build more than one million homes.

Third, even if the 1.2 million new home target could magically be achieved, it would create a raft of problems.

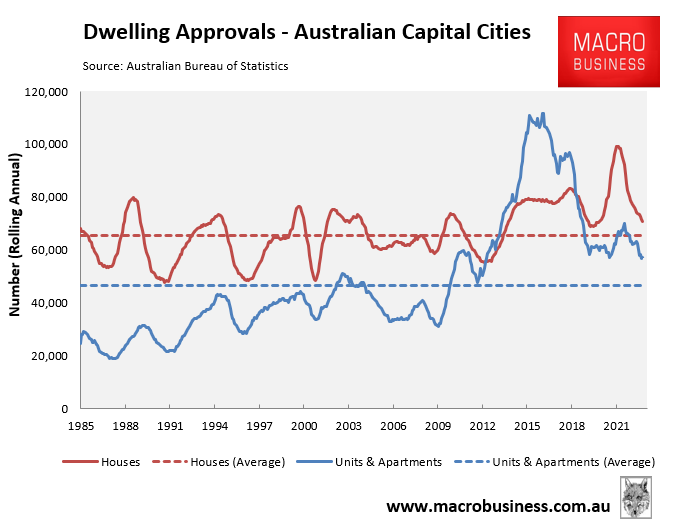

Australia experienced record housing construction boom last decade, as illustrated below:

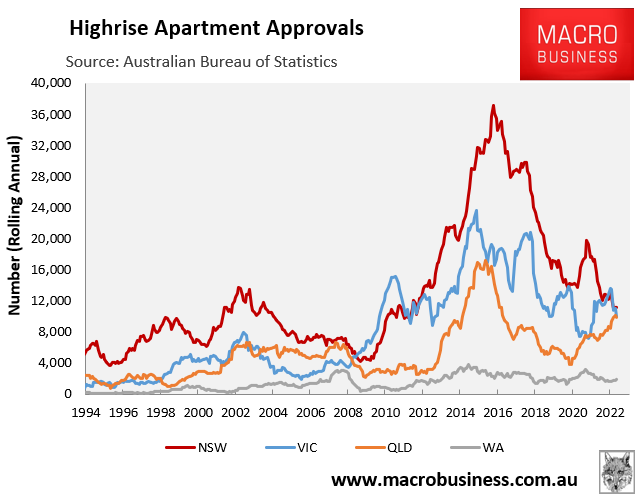

This boom was driven by high-rise apartments:

The rapid construction of apartments was accompanied by a serious degradation in quality, with thousands of apartments suffering from cracking, water leaks, structural balcony issues, and flammable cladding.

What does Albo think will happen when an even higher volume of apartments is built in such a short period of time?

Obviously, quality will be degraded further, resulting in more defects and costly rectification.

Thus, Albo’s 1.2 million homes pledge is not only unrealistic but also undesirable.

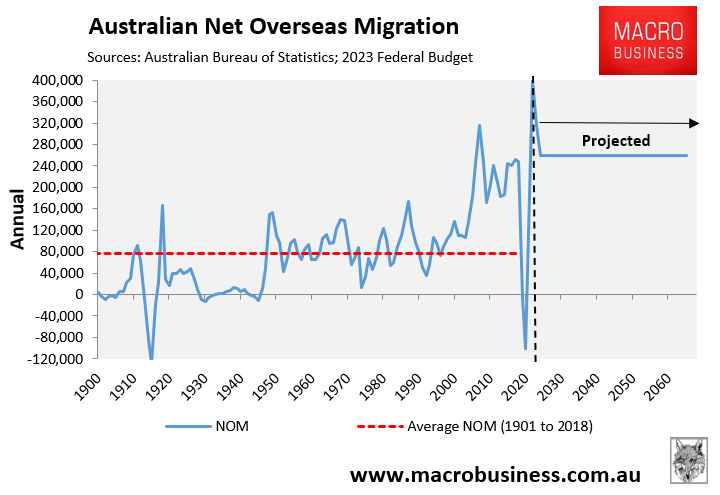

The better solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to take the pressure off demand by lowering immigration to sensible and sustainable levels in line with the historical average (around 100,000 a year):

That would solve the housing crisis and remove the need to bulldoze Australian suburbs into defective high-rise apartments.

Australians also do not support high levels of immigration. So by cutting it, Albo would be giving voters what they want rather than pissing on them.

Nobody voted for Albo’s Giant Australia. And nobody wants their suburbs turned into high-rise slums.