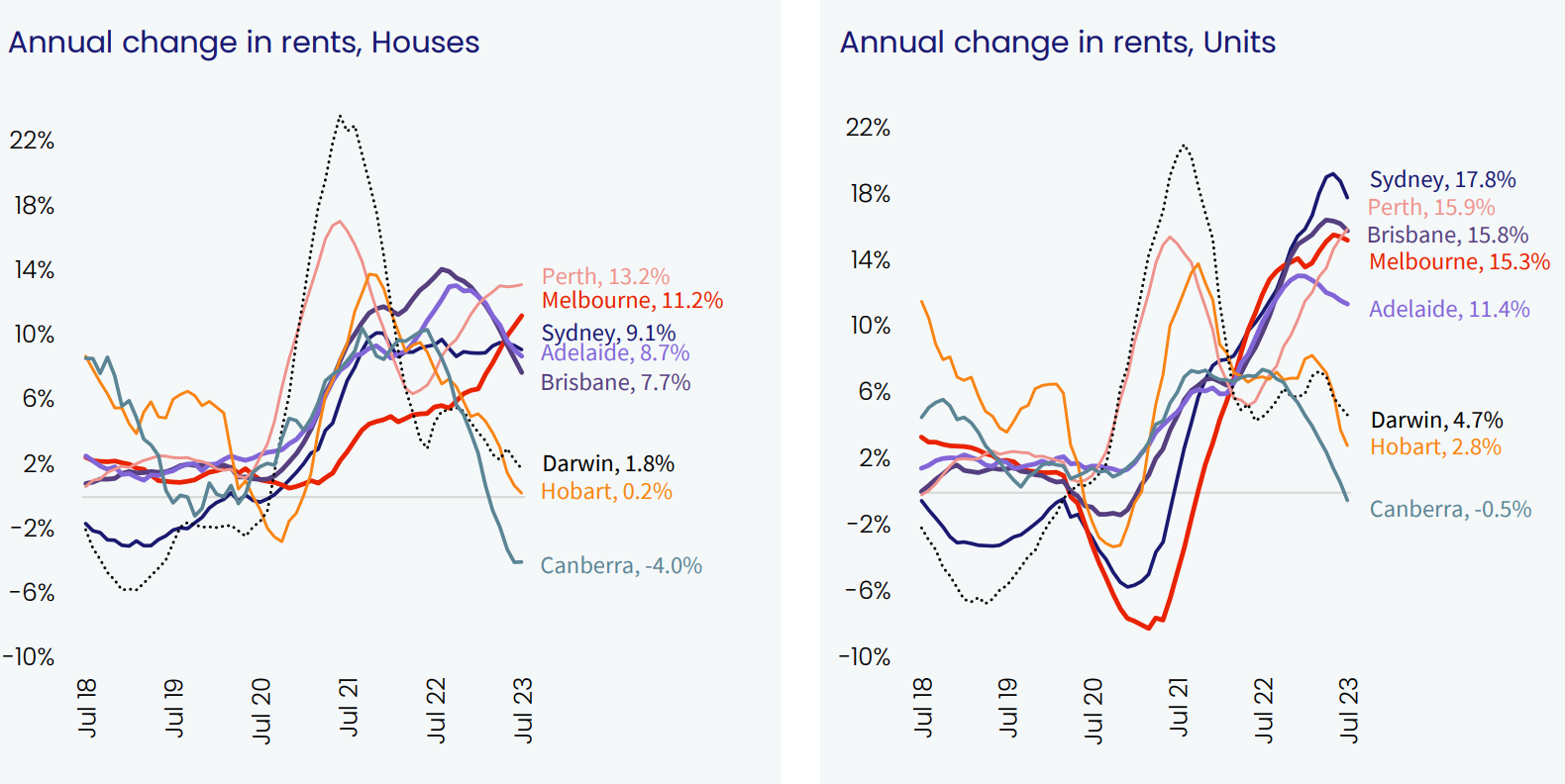

Australia is currently facing paradoxical conditions: there is a vast oversupply of empty office buildings at the same time as there is an acute shortage of apartments rentals, which is driving rents into the stratosphere across the major capital cities:

Given working from home has become an entrenched feature of the Australian economy post-pandemic, one seemingly logical solution is to turn these empty office towers into high-rise apartments.

Doug Southwell of Scott Carver Architecture worked on the redevelopment of a 1970s commercial building on the outskirts of Hyde Park into residential units.

He told The ABC that his company has been receiving an increasing number of inquiries from developers about potential conversion projects.

“It’s certainly become very popular as a topic, particularly with reduced demand for commercial space in CBDs, with work from home and other changing patterns,” the architect said.

“If it’s done well, there are great opportunities”.

Southwell said office are usually well-located and feature high ceilings.

He also stated that reusing an existing building was usually faster than building from scratch, which is vital in a tight housing market.

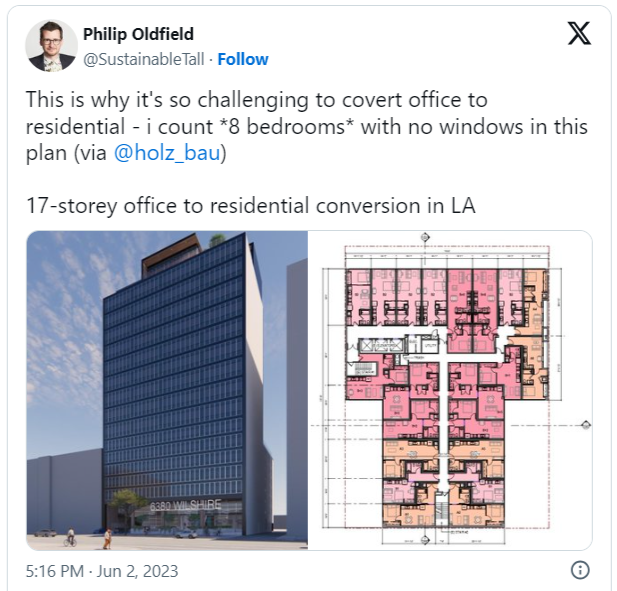

However, there are also costly barriers to converting office tower into residential apartments, including:

- Complying with housing requirements for lighting, ventilation and air conditioning;

- Transforming an office’s large floor plans into individual dwellings;

- Installing bathrooms and kitchens in new units, complete with water and sewage.

- Trenching into floors to ensure sewage pipes have appropriate room without compromising the building’s structure.

Some apartments are more suited to conversion than others. The size and shape of the floor plans are the main determinants.

For these reasons, Professor Philip Oldfield, Head of the School of Built Environment at UNSW, said office conversions were “no silver bullet” to the housing crisis.

“Let’s say there’s 50 empty buildings in the Sydney CBD, maybe only five to 10 will be suitable to be converted to residential”, he said.

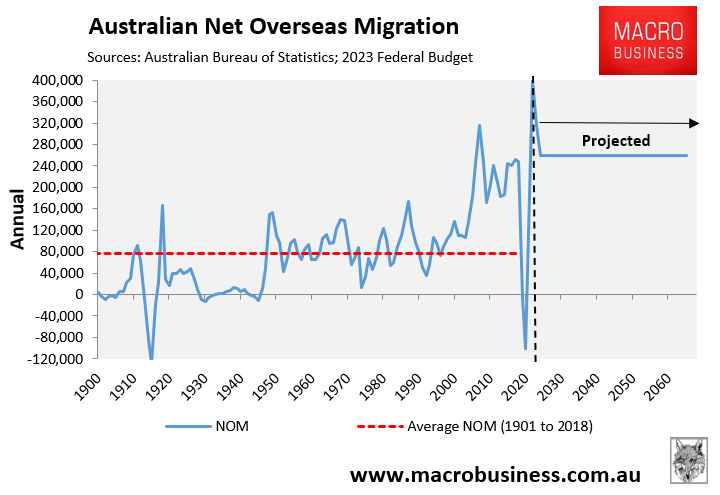

The ultimate solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to slow the rate of immigration to a level that enables Australia to catch-up with its accumulated housing and infrastructure shortage.

Otherwise Australia’s housing crisis will continue to worsen.

An average annual intake of 100,000 net overseas migration, which is around the historical average, is the right number.