When Australia’s population was 19.3 million people in 2001, Treasurer Peter Costello issued the first Intergenerational Report (IGR).

The 2001 IGR projected that Australia’s population would be 25.7 million in 2050, with yearly net overseas migration (NOM) projected to be 90,000.

The following year, in 2002, a Senate Inquiry convened by the Howard Government on behalf of the business lobby complained of “serious skill shortages and skill gaps” in Australia and warned that unless the nation did something about it – i.e. imported a large number of workers – the economy would not develop and would eventually regress.

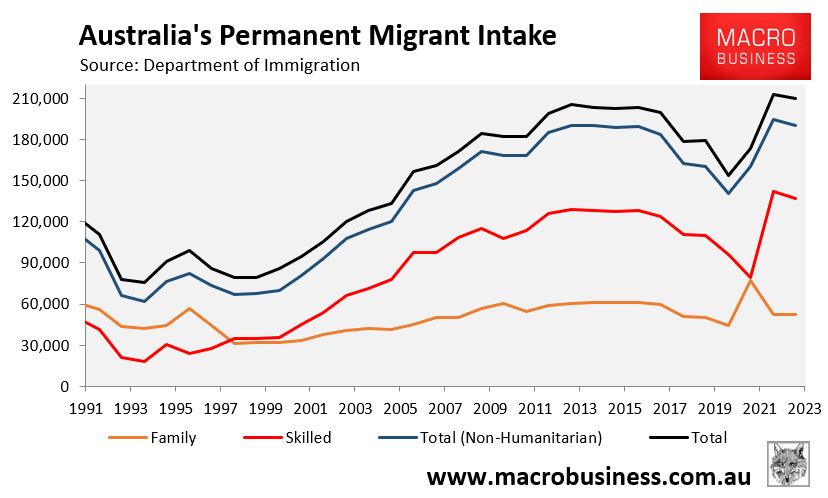

In response, the Howard Government gradually boosted permanent immigration intake from 93,000 to 150,000 in 2007.

Following Labor and Coalition governments lifted the permanent migrant intake toward its present planning level of 190,000 per year:

The number of humanitarian migrants admitted has also increased from 12,300 in 2002 to 20,000 this financial year:

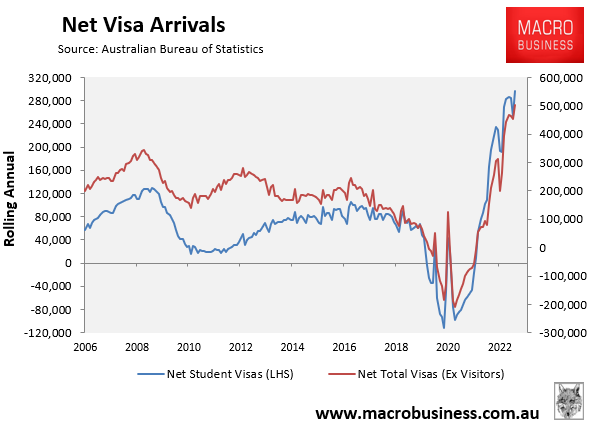

The former Gillard government also considerably enhanced post-study work rights for international students following a strategic review of the student visa programme in 2011 (‘the Knight review’).

Graduate (Subclass 485) visa holders were not required to be qualified for any of the jobs in the Skilled Occupation List positions. They did not require a firm job offer from an employer. They were not compelled to be paid a minimum wage. They also do not have to locate a job that is relevant to their qualifications or require a specific level of ability.

Graduate visa holders became free to work or study for any employer. And their visa remains valid even if they are unable to find work.

The Knight review was firmly in favour of expanding post-study work rights since it would significantly boost Australia’s appeal as a destination for overseas students, benefiting both universities and companies in Australia.

As a result, international education transformed into an immigration industry.

Graduate (485) visas in Australia are among the most appealing of their kind in the world since they grant full employment rights.

They are also highly coveted by international students because they are viewed as a means of obtaining permanent residency.

International student visas increased dramatically, resulting in a significant increase in temporary migration alongside the permanent migrant intake:

At last year’s Jobs & Skills Summit, the Albanese Government extended the term of post-study graduate visas and recently inked two migration agreements with India, which will provide Indians with automatic five-year student visas and eight-year post-study work visas, among other things.

The Albanese Government has also given international students an easier path to permanent residency by abolishing the Genuine Student Test on visa applications.

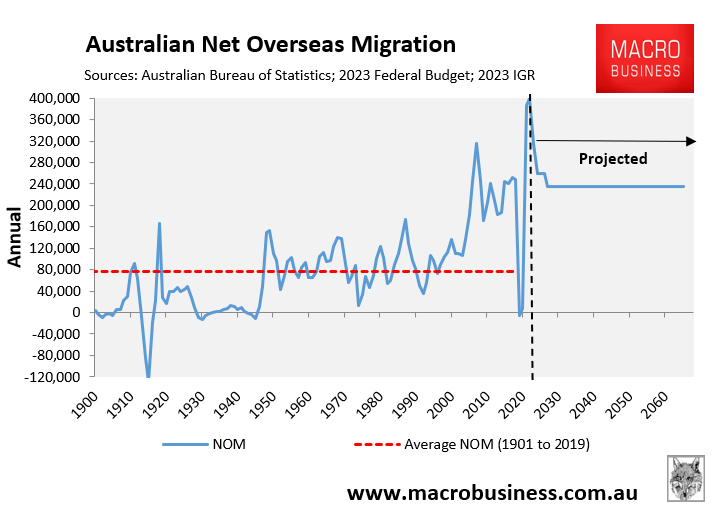

The rise in permanent and temporary migration increased Australia’s NOM from roughly 90,000 in the 60 years following WWII to 210,000 since (including the negative years due to the pandemic):

Accordingly, Australia reached the 25.7 million population prediction from the 2001 IGR 29 years early in 2021, having grown by an astonishing 6.4 million people during that 20-year span.

Australia’s biggest cities grew dramatically throughout this period as well.

Melbourne, for example, had a population of 3.3 million in 2001, while Sydney had a population of 3.9 million.

By the end of 2022, Melbourne’s population had increased by 1.7 million (51%) to 5 million people, while Sydney’s population had increased by 1.3 million (34%) to 5.3 million people.

Big Australia locked-in:

The 2023 federal budget projected that Australia’s population would grow by 2.18 million people (equal to the population of Perth) over the next five years, owing to 1.5 million net overseas migrant arrivals (similar to the population of Adelaide).

The 2023 IGR, released this week, projects that Australia’s population would reach 40.5 million by 2062-63, owing to annual NOM of 235,000.

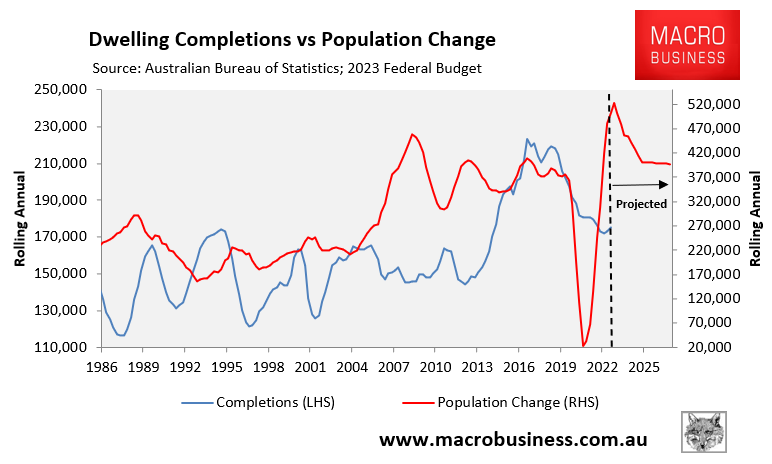

Australia has not been able to keep up with the 7.4 million population increase this century.

How will it deal with an additional 14.2 million residents over the next 40 years, the equivalent of adding a combined Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide to Australia’s existing population of 26.3 million?

Australia took 216 years to reach a population of 20 million people in 2004.

However, the 2023 IGR predicts that the country would gain another 20.5 million people in little under 60 years, with Melbourne and Sydney becoming megacities of around nine million people.

The ‘Australian way of life’ faces extinction:

Australians are already suffering from a chronic housing crisis, which has driven up rents to exorbitant levels and forced thousands of people into sharing housing or homelessness.

This housing shortfall is the result of decades of high immigration, which has driven demand above the country’s capacity to supply new homes:

How will housing supply ever catch up with demand when Australia’s population is expected to rise by 355,000 people per year on average over the next 40 years due to strong NOM?

Over the last two decades, Australia has not built enough dwellings. What makes anyone think we’ll get better results in the next 40 years?

Furthermore, do Australians want to live in high-rise apartment buildings? Because with a population of 40.5 million, that will become the norm.

The same can be said about Australia’s chronic infrastructure shortages.

This century’s 7.4 million population boom has crammed everything in sight, including roads, public transportation networks, hospitals, and schools.

How will Australia catch up on its infrastructure deficit, let alone provide infrastructure for an additional 14.2 million people?

What about the water supply in Australia? Only four years ago, Australia was suffering from severe drought, with water supplies running low.

What will happen the next time there is a drought and Australia has to provide water to millions more people?

To supply water to the additional 14.2 million people, Australia will need to construct a number of costly, energy-intensive, and environmentally damaging water desalination plants. This will also result in higher water bills.

This leads us to Australia’s climate “net zero” goal.

As part of a transition to “net zero” emissions by 2050, the Albanese Government has promised to reduce Australia’s carbon emissions by 43% in 2030 compared to 2005.

How can Australia attain “net zero” while its population is expected to rise by 14.2 million people, or 54%?

It is estimated that building construction, operation, and maintenance account for around one-quarter of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The estimated 14.2 million increase in Australia’s population would necessitate the building of at least 5.5 million new homes as well as significant new infrastructure.

This building, as well as the additional 14.2 million energy users and consumers, would increase Australia’s carbon emissions.

The broader environmental consequences of land removal and resource use by the increased population would also be disastrous.

The 2021 State of the Environment Report rated pressures from population growth as having a “very high impact” on the environment.

The economic benefits of high immigration are exaggerated:

Having more people in the economy spending and consuming is good for economic growth in aggregate.

Businesses benefit from having more customers to sell to as well as a broader pool of workers to choose from: it’s a win-win situation for them.

The impact of heavy immigration on ordinary Australians’ living standards is less favourable, because they must compete harder for housing and jobs with new migrants, while infrastructure, services, and the natural environment are overburdened.

Population growth also does not increase gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

According to the IGR, a robust immigration program is required to counterbalance an ageing population.

The idea goes that migrants are often younger than the native population. Therefore, importing people through immigration lowers the average age of the population, eliminating the “problem” of ageing.

Anyone with a smidgeon of common sense can see that this reasoning is flawed because migrants age as well.

Immigration can only assist to postpone population ageing while also introducing a slew of additional economic and environmental costs associated with having a much bigger population, as discussed above.

Importing more migrants to solve population ageing is ‘can-kick economics’, because today’s migrants will age and contribute to age-related difficulties in 40 years.

This ageing will necessitate the influx of even more migrants, which is the definition of a ‘ponzi scheme’.

Increasing productivity and worker participation are ultimately the only solutions to mitigate the negative economic effects of population ageing.

Both solutions are compromised by large levels of immigration, which reduces the capital-to-labor ratio (a phenomenon known as “capital shallowing”).

Shane Oliver, chief economist at AMP, highlighted this capital shallowing earlier this month:

“Very strong population growth with an inadequate infrastructure and housing supply response has led to urban congestion and poor housing affordability, which contribute to poor productivity growth”.

Finally, the IGR contends that maintaining high levels of immigration is beneficial to the federal budget because it increases the number of workers who pay taxes.

While increased immigration benefits the federal budget by increasing income tax receipts, it simply shifts the expenses to state budgets (by additional hospital, education, and infrastructure funding) and private individuals (via user fees such as toll roads and higher housing costs).

That’s why state governments have privatised anything that isn’t bolted down in a frantic bid to raise funds for more infrastructure investment and services, which never keep up with population growth.

The best solution to Australia’s budget problems is to simply imitate Norway and appropriately tax Australia’s tremendous mineral resources.

Thanks to its well-designed super profits tax, the Norwegian government earned $137 billion from the oil and gas industry last year.

As a result, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund grew to nearly $1.8 trillion, despite the fact that it is shared by only 5.3 million people.

Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund is now valued at almost $340,000 per person, putting it in a strong position to sustain its ageing population.

If policymakers merely taxed our resources properly, Australians would not have to worry about federal budget debt.

Australia would also not have to grow its population like a lab experiment through mass immigration to fill gaps in the federal budget while shifting the costs to the states and residents at large.

We need a smart Australia, not a ponzi-based Australia that hides its economic demise behind record population increase.

Regrettably, the Albanese Government has doubled down on the disastrous “Big Australia” ponzi economic model by launching on of the world’s largest immigration programs.

In turn, Australians will confront a crowded, high-rise future in a deteriorated environment.