Below is a new report by Bob Birrell and Katharine Betts from the Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI) explaining why the voice referendum is failing.

Introduction

We do not enter this arena out of lack of concern for continuing Indigenous community disadvantage. It may be that the voice referendum, if it succeeds, will help and if this is the case so much the better.

Rather, our entry is motivated by concerns about the way in which the Government and other voice advocates have pressed their case.

By August 2023, most opinion polls indicated that the voice referendum is likely to fail. How could this be?

In the aftermath of the May 2022 federal election, the victorious Labor Party had embraced the voice cause. Labor’s victory was widely interpreted as a prelude to an electoral swing towards the party’s economic and cultural policies.

Why the voice is failing – an outline

It seemed to voice advocates that the move to enhance the Indigenous community’s political influence, and therefore to diminish its disadvantage, would have majority community support.

To most advocates, opposition implied a mean and churlish attitude towards the Indigenous community which surely was confined to a small minority.

The response from advocates as it has become evident that most voters do not support voice has been bewilderment and hurt.

Two sets of explanations dominate advocates’ thinking.

The first is that voters have been scared off by critics’ claims that the voice will give the Indigenous community far greater influence over national policy than has been previously acknowledged.

The second is that the No vote reflects resentment towards the corporate and other elites prominent in advocating the cause. In addition, many commentators assert that this opposition hides racist attitudes towards Indigenous people.

This is an inexact science. It may be that these explanations have indeed been influential in adding to the No vote.

However, we offer a different explanation, backed up by our, and others’, analysis of the opinion polls. This argues that most No voters (a majority of whom are non-graduates) have quite rational reasons for their stance, based on their nationalistic values.

By nationalism we refer to beliefs that the nation is the source of political and economic progress and, for a nationalist, should be the prime focus of citizen identity. It also explains why they are not likely to be shamed into changing their position.

From their perspective, all communities should be treated equally, including the Indigenous community and that it is advocates for Indigenous separatism who are morally suspect on the issue.

Though initially most voters did support the voice, in recent months the tide has turned. Support amongst graduate voters remains strong, but has ebbed away amongst other voters, especially those who are non-graduates (who comprise some two-thirds of the electorate).

Our research in successive Tapri polls explains why this is the case. It indicates that non-graduates are much more likely to hold nationalist values than are graduates and that, as a consequence, they tend to see the vote on the voice as a challenge to these values.

The rise and fall of the voice in the polls

On election night in May 2022, the new Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese, committed his government to implement, in full, the Indigenous leaders’ agenda. This had been spelled out in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Its aspiration was for the creation of an Indigenous community voice which would be enshrined in the Australian Constitution after being put to Australian voters in a promised referendum.

The voice would represent the Indigenous community’s policy views both to Parliament and to executive government. Furthermore, according to the Statement from the Heart, the voice was to be a prelude to subsequent negotiations leading to a Treaty.

It was a bold statement of Indigenous community leaders’ aspirations for a degree of separatism, a form of sovereignty, within the larger Australian community.

Albanese’s commitment to this aspiration, confirmed a few months later at the July 2022 Garma Festival, marked the end of Labor’s pre-election caution on this and other progressive issues. This caution had reflected the recognition amongst Party strategists that the electorate was wary of such reforms. The caution has since been abandoned.

A key reason for this confidence is that the May electoral outcome seemed to imply a major change in voters’ policy inclinations, with the Liberal Party being the big loser.

The authoritative ANU study of the 2022 Federal Election outcome had reported that there had been an unprecedented swing on the part of younger voters away from the Coalition. It added that ‘changes of this magnitude and this pace are rare in Australian electoral history’.

Their votes had swung towards progressive parties (the ALP and the Greens) and that, as a result, so the ANU study concluded, this presented the Coalition with a serious problem.

Since these voters were considered to represent future trends (as they maintained their views over time) many commentators concluded, along with Paul Kelly, the leading opinion writer at The Australian, that: ‘The Coalition’s future is in doubt’.

Subsequent opinion polls in 2022 and well into 2023 showing Labor ascendency over the Coalition seemed to confirm this thesis.

We are not the first to label Labor’s policy commitments as a form of hubris. Yet at the time, at least in reference to the voice, the claim of hubris seemed justified. The Age’s Resolve poll, published in August 2022, reported that 63 per cent of voters supported the proposed voice referendum.

To understand the electoral hazards of Labor’s commitments and their implications for the voice referendum, we need to step back for the moment to frame what has since happened within a larger electoral context.

The great divide on cultural issues in Australia

Australian electoral outcomes revolve around two major sets of issues. One concerns economic matters. On these issues, progressives have advocated a more open, competitive economy.

However, for ordinary people, their focus is on whether their income, job prospects and financial futures are being prioritised, which usually translates into a more protective stance.

The other set concerns cultural issues. These have played an increasing role in electoral outcomes since the 1980s. This is when progressives began staking out a cultural agenda that they regarded as vital to their aspirations for Australia’s future.

In the 1980s and since, support for a generous immigration policy as well as for Indigenous advancement, including Indigenous leaders’ goals that their community be regarded as a separate, sovereign entity, have been important components of this agenda.

Progressive views on Indigenous advancement have come to be regarded as key markers of progressive identity. This has been manifested in innumerable demonstrations, as with marches, sorry days and apology ceremonies.

As a result, any dissent from these views tends to be regarded as immoral and is often countered by public shaming.

We have documented this process in reference to Labor’s high migration agenda. The Tapri national poll conducted during September 2022 found that most voters were opposed to Labor’s high immigration policy.

It also found that a large share of these voters felt that they could not speak out on the issue because of fears that they risked shaming as their views would be perceived as racist.

We did not ask respondents in our poll whether those opposed to the voice feared a similar shaming. However, a recent Essential poll found that 67 percent of respondents say that ‘People are scared to say what they really think because they don’t want to be labelled as racist’.

Who are the cultural progressives and who are those who oppose their agenda?

Most progressives are graduates, and most of those who oppose, or do not support, their causes are non-graduates.

There is no one-to-one correlation, but the tendency is strong and becoming stronger as cultural issues play an increasingly important role in political outcomes.

There is a literature on the matter too vast to detail here. Suffice it to say that the Australian experience mirrors that found across Europe and North America.

Graduates predominate in progressive ranks for at least two reasons. First, their university education informs them about progressive values. And second, their qualifications enable them to gain the most career benefits from an economy open to the world, which, as noted, is a core feature of progressive thinking.

Why don’t non-graduates also embrace these aspirations? Partly it is because they have been less exposed to progressive values and have enjoyed fewer career benefits from an open economy.

But the main reason is that most are nationalists. The theory is that non-graduates have a rational interest in identifying with the national cause and are thus suspicious of any movements that weaken this cause. They hold these views because they regard a strong nation as central to protecting them from the buffeting of the international economy.

The nation is their community of fate which they regard as their ultimate security blanket. They therefore tend not to support minority autonomy, diversity or multiculturalism, where it is seen as weakening national solidarity.

This predisposition shows up in very strong non-graduate support (relative to graduates) for maximising Australian self-reliance in industry and the prioritisation of residents’ interests relative to new immigrants in access to employment opportunities.

This generalisation is based on successive Tapri and other opinion polls on relevant issues.

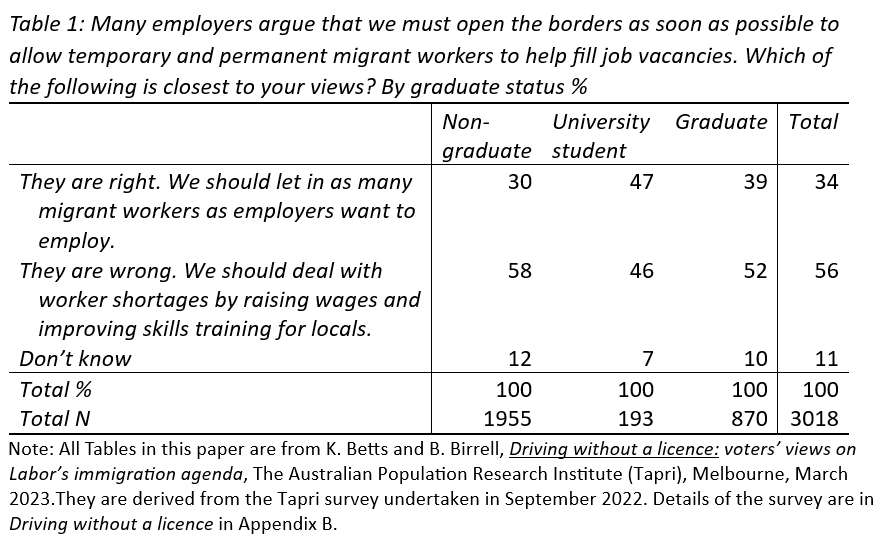

Here is an example taken from the Tapri September 2022 national poll of voters. This asked about the relative priority that should be given to residents and new migrants in dealing with labour market shortages.

The non-graduate preference for residents was much stronger than was the case for university students or graduates.

Given non-graduates’ views about the centrality of the nation in determining their fate, they tend to oppose any causes that imply a weakening of national solidarity. The promotion of Indigenous separatism, built around Indigenous sovereignty, is a case in point.

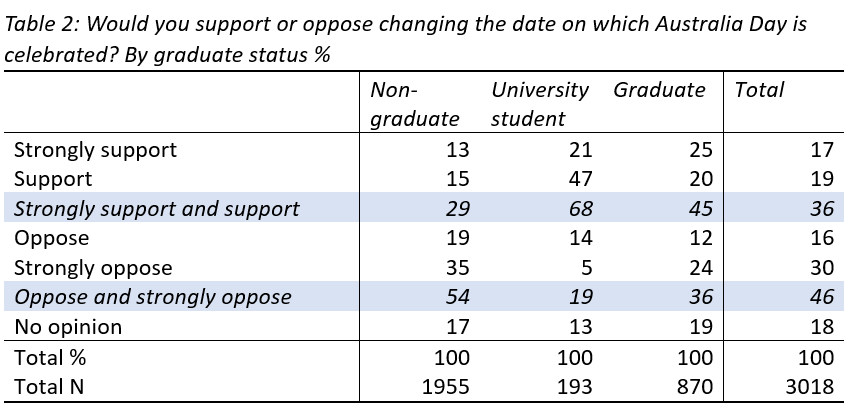

The debate about changing the date for celebration of Australia Day provides an opportunity to test this hypothesis. Table 2 sets the scene.

Table 2 shows that 54 per cent of non-graduates oppose a change in the date compared with 36 per cent of graduates.

Few voters at the time would have been unaware that advocates for changing the date often accompany this position with accusations that Australia Day is akin to invasion day.

Advocates for changing the date have been outspoken in declaring that their support endorses Indigenous leaders’ aspirations for autonomy and sovereignty within the larger Australian community.

By contrast, non-graduates appear to interpret the Australia Day debate as a challenge to their nationalistic ideals of one Australia, and thus, on these grounds, mostly reject changing the date.

What is important for understanding the prospects for voice, is that the sentiment behind this opposition to changing the date for Australia Day, appears to have shaped their intended vote on the Referendum.

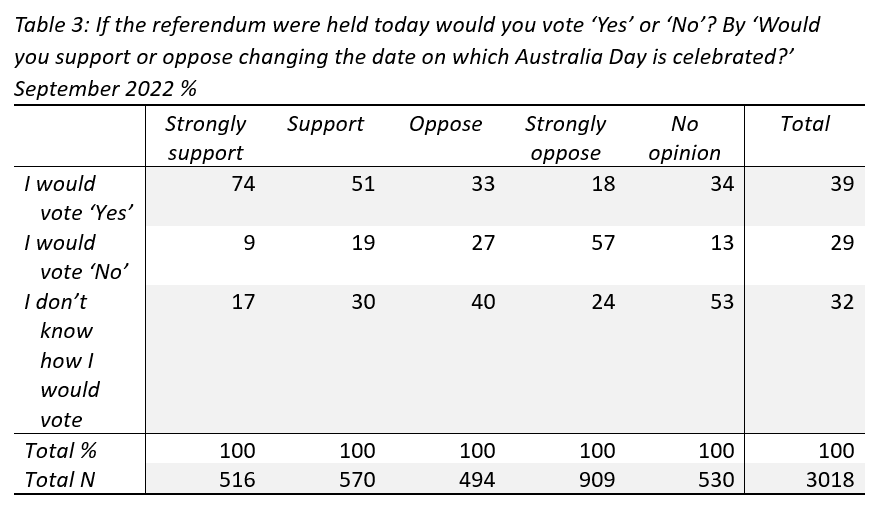

As Table 3 shows, a large majority of those opposed to changing the date intended to vote No and conversely that a big majority of those supporting the change intended to vote Yes.

Current implications for the prospects of the voice Referendum

Notwithstanding Albanese’s post-election support for Indigenous community aspirations, initial polling on the referendum showed (soft) support – reflecting a high don’t-know component.

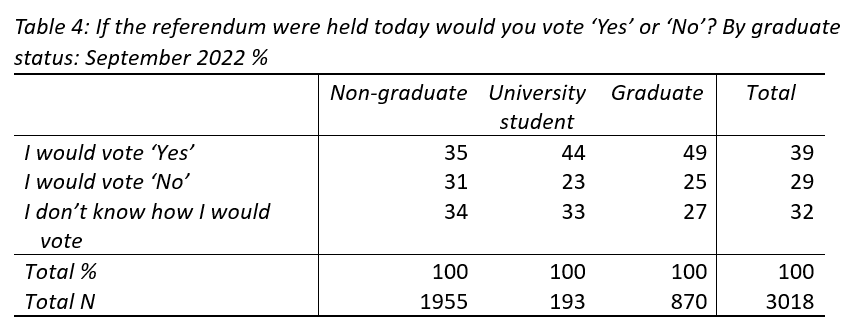

This was also the case when we asked the voting intentions question in September 2022. This was prefixed by another question about how much they had heard about the voice.

More than half said they had heard hardly anything or nothing at all. Nevertheless, of those who were prepared to indicate their voting intention, a plurality supported a Yes vote (Table 4).

As Table 4 shows, graduates were far more likely than non-graduates to support the voice. But it is notable that as of September 2022, non-graduates were also supportive, with a 35/31 Yes/No split.

It seems that this support continued until at least April 2023, before the final wording of the referendum was settled and Parliament delivered its support for putting the referendum to the voters.

Since April, however, the share of support for the voice has declined, mainly because many in the don’t know category have moved into the No category. This is particularly notable for non-graduate voters.

Our hypothesis is that this increase in the No voting share has been prompted by an intensification of debate on the issue.

Few voters could be unaware that advocates frame their support within a larger progressive agenda that prioritises minority, and especially Indigenous autonomy and sovereignty. This, in turn, so we argue, is likely to prompt opposition to the cause, especially amongst non-graduates.

Recent Newspoll analysis supports this expectation. On August 7, The Australian provided an analysis of the accumulated responses in its polls between May 31 and June 15, 2023. They enable an analysis of opinion on the voice by education, age, region, and several other variables.

The results show that support from graduates (which, as noted above, was strong at the time of our September 2022 survey), has been sustained.

Though the No share had increased (as some don’t knows switched into this category) the Yes vote remained well ahead of the No vote. For graduates the Yes/No split was 55/37 in favour of Yes (compared with 49/25 in the Tapri survey).

However, this was not the case for non-graduates. The share of those supporting the voice had increased a bit. But the No share had sharply increased.

At the time of the Tapri survey the Yes/No split for non-graduates by 35/31. By the time of the late May/June Newspolls the split for non-graduates was 39/49. The No vote had increased massively from 31 per cent to 49 per cent.

If there is no change in attitudes prior to the referendum vote, the voice cannot win because the non-graduate category makes up two thirds of the electorate.

In our view the trend towards No amongst non-graduates is likely to deepen. This is because, as Yes leaders realise that voter support for their cause is fading, they respond by intensifying the moral urgency of their advocacy.

This is the case for the chief advocate, the Prime Minister, who has linked his support for the voice with progressive support for Indigenous autonomy and sovereignty.

In so doing more of the nationalists among non-graduate ranks (and other parts of the Australian community) are likely to conclude that the voice is part of a larger progressive cultural agenda that is contrary to their own cultural priorities. This will prompt a further slide in support for the Yes cause.

Other commentators do not share our judgement. Far from it.

The response to the decline in support for voice has been greeted with bemusement within Labor and progressive media circles. How could this be given Labor’s alleged political hegemony and the strong and increasingly passionate advocacy of Indigenous leaders and progressive opinion leaders?

There is a cornucopia of hypotheses.

One of the most common is that with increasing debate about the voice more voters have come to suspect that there may be long-term and perhaps costly consequences.

One widely flagged outcome stems from enshrining the voice in the Constitution. This, so critics argue, would give the High Court greater opportunity to make judgements requiring the Australian Government to take account of all voice policy recommendations, including those on foreign affairs and trade.

There is some doubt, however, that many ordinary people would be aware of such possibilities.

Another prominent explanation is that the fall off in support for the voice reflects voters’ material concerns, such as those deriving from recent increases in the cost of living.

Simon Benson, the chief commentator in The Australian on Newspoll results, has also suggested that this fall is notable amongst female voters. The implication is that, with these concerns increasingly uppermost in voters’ minds, they have become impatient that so much Government attention being given to the voice issue. Perhaps.

A broader version of this idea is that, as elite advocacy for the voice cause has become more prominent, including from big corporates, it is prompting resentment amongst less affluent voters.

This is the view of Kos Samaras, the high-profile principal of the RedBridge polling firm. His polling indicates that the slump in support for Yes is pronounced among lower income, non-university educated voters living in the mortgage belt, people who are facing increased costs of living while simultaneously coping with increased high mortgage payments.

Samaras proposes that this has generated a ‘politics of grievance’.

While it is plausible, this argument implies a mean-spirited reaction. These voters are presumed to be willing to oppose Indigenous advancements because elites, whom they resent, are advocating for the Indigenous cause.

Such a hypothesis seems unfair and in any case is not supported by the polling evidence.

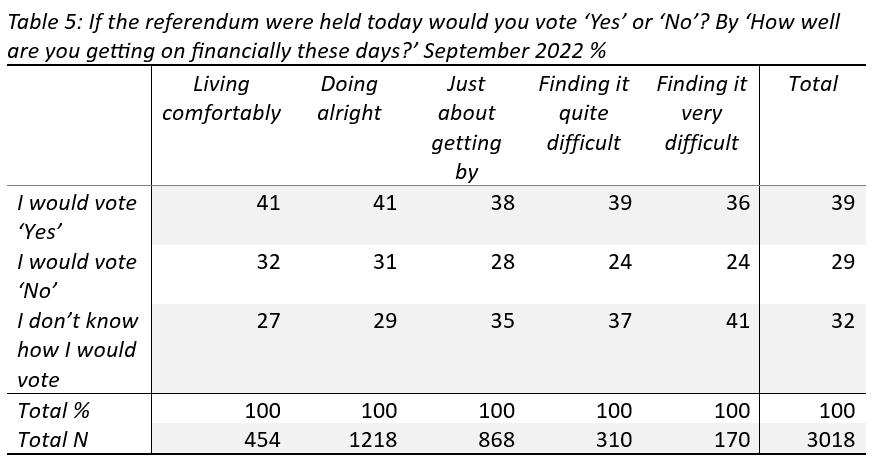

Tapri’s September 2022 national poll asked respondents about their financial situation. Respondents were asked ‘how well are you getting on financially these days?’. The alternatives were ‘living comfortably, doing alright, just getting by, finding it quite difficult or finding it very difficult’.

A strikingly high share (44.6 %) reported that they were in one of the three financially challenged categories – including the ‘just getting by’ group.

Table 5 shows respondents by their intended vote on the voice by each financial category.

There was little fall off in support for voice by the severity of their financial situation. Even those indicating that they were ‘finding it very difficult’ said that they intended to vote for the voice by a 36/24 margin.

Age versus non-graduate explanations

The Australian’s recent analysis of the late May to June 15 Newspolls opens up another range of plausible interpretations for the decline in the voice vote.

While these polls support our argument about the importance of the graduate/non-graduate divide, they also indicate that there is a wide divide in favour of No amongst voters on other dimensions. These include voters’ age, income level and regional location.

Why prioritise the education factor as we have done?

Simon Benson, in his commentary on the Newspoll findings chooses to focus on the age factor. In the case of those aged 65+ the Yes/No split was 28/64, and in the case of those aged 50-64 it was 34/54.

The age factor can be subsumed within our theory.

For a start, most voters in the 50 plus age group are non-graduates, so they have not experienced the socialisation in progressive causes that accompanies a university education today.

Furthermore, the aged have had decades of exposure to the nationalist commitments that prevailed from the 1950s to the 1980s.

We refer here to the celebration of national achievement and identity associated with Australia’s sporting and economic progress (before all this was challenged by cultural progressives).

But surely an important driver of older voters’ scepticism about the merits of voice is that these voters are approaching, or are in, the ages when they are most likely to value the protection of a strong state and supportive national solidarity.

They have immediate concerns about state assistance for retirement incomes, and state support for medical and hospital services.

Few of them would fail to see that Australia’s capacity to respond to their needs would be threatened should Australia divide along Indigenous/non-Indigenous, wider ethnicity and/or cultural lines.

In this sense age is not a different explanation from the graduate/non-graduate divide, but rather is at the cutting edge of this explanation.

Summary

The seemingly inexorable decline in support for the voice has generated bemusement within progressive circles. The domination of Labor and the Greens at the May 2022 election was widely seen as putting these parties in an impregnable electoral position.

However, Labor’s strength on economic issues (in most voters’ eyes) hid vulnerability on the cultural front, which the voice initiative has exposed.

Commentators have put forward many explanations for this outcome.

We have focused on (and questioned) claims that the cost-of-living stresses lower income households are experiencing explain their (and by implication non-graduates’) rejection of voice.

This rejection is seen as a mean-spirited outcome driven by envy or by resentment of the elites prominent in advocating for voice.

The fallback position for some of those struggling to find an explanation is that the much of the No vote is based on racism. While we have not highlighted this accusation, it is widespread.

For example, prominent columnist, Niki Savva, writes that the Coalition’s negativism towards voice and other policy issues, is brutal and ugly. ‘It risks inflaming community tensions on race and immigration’.

On the same day, The Age highlighted Independent Senator and anti-voice campaigner, Lidia Thorpe’s opinion that Anthony Albanese should ditch the referendum because it is emboldening racists.

In our view the main explanation for the fall-off in the Yes vote is that the voice is seen by many voters (especially those who are non-graduates) as a challenge to their nationalist values.

From their perspective a strong and united nation is important as a protector of their economic interests. To them the voice represents a potential breakdown in that unity.

The progressive elite has reacted to the slip in the voice vote by pressing the moral intensity of their cause, with the implication that a No vote is shameful, even racist.

Shaming is not working because, at the core of non-graduates’ nationalistic values, is the presumption that all Australians are equal regardless of the community they identify with.

For them it is voice advocates who are racists, because they are advocating for separate political representation and sovereignty for one racially distinct group, the Indigenous community.

We are not saying that the opposition to voice is a prelude to the political resurgence of the right. Yes, cultural cleavages are providing the basis for a recovery for the Coalition.

But on economic issues the Coalition, with its continued support for big-business and neo-liberal austerity, is way behind Labor and the Greens.