When I began studying economics in high school, we were first taught the foundation concept of “supply and demand”.

However, when you read the commentary and analysis surrounding the Australian housing market, you would believe there is only a supply side. Because the demand side rarely gets a mention.

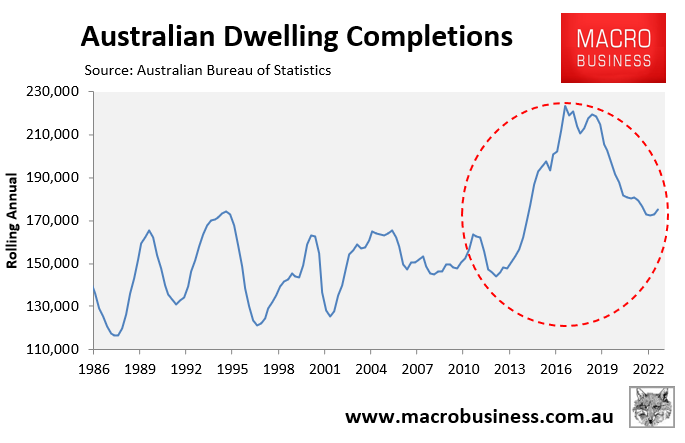

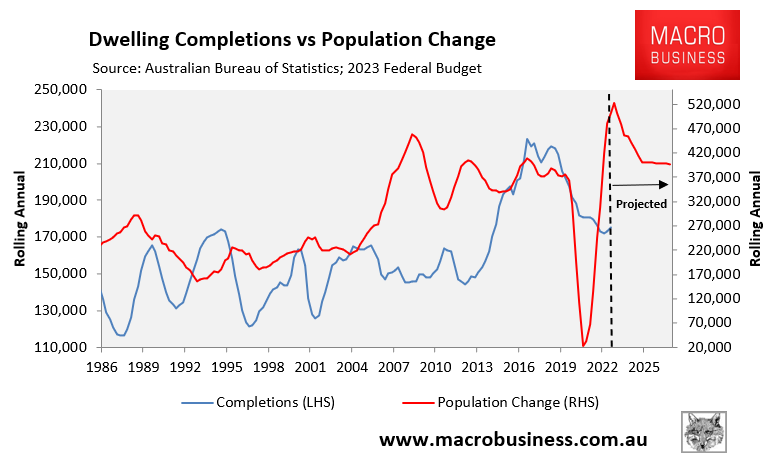

This narrative misses the fact that Australia enjoyed the largest housing construction boom in history last decade, during the 2010s. As a nation, we built more homes than ever before, as shown below:

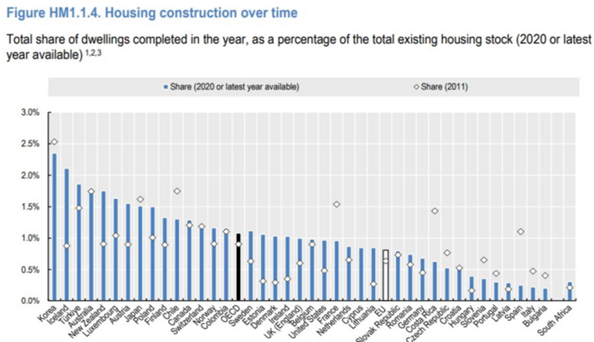

According to the OECD’s Affordable Housing Database, Australia has built much more houses per capita than the majority of other OECD countries:

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database

In 2020, Australia ranked fourth in the OECD for home building. Australia’s residential construction rate also remained constant from 2011.

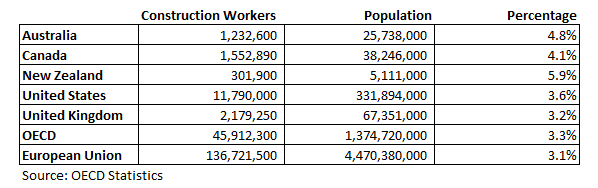

In addition, Australia has one of the largest proportions of construction workers in the OECD:

Australia is in the grip of an unprecedented housing crisis. Rents have skyrocketed. A growing number of people are living in group homes. More Australians are being forced to become homeless. There’s a lot of anxiety in the air.

In response, the National Cabinet has pledged to constructing 1.2 million new dwellings over a five-year period beginning 1 July, 2024.

These 1.2 million dwellings will not be “built” by the federal, state, or territorial governments. Their strategy is to ease planning and zoning laws to allow for greater density in the hopes that private developers will build them.

It is instructive that the Albanese Government’s contribution to the supply objective through the Housing Australia Future Fund will be only 30,000 dwellings, if it ever passes the Senate.

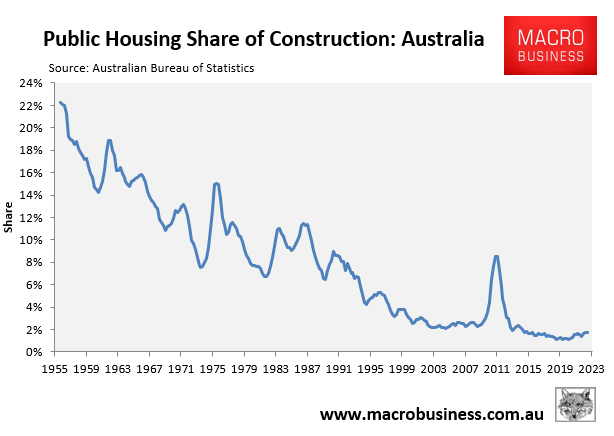

That is only 2.5% of the total target, which is comparable to current levels of public housing construction by state and territory governments:

For a variety of reasons, the National Cabinet’s 1.2 million housing target is doomed to fail.

First, developers will not want to overwhelm the market with new supply since it would negatively impact their profits. Private developers have an incentive to drip-feed supply in order to maintain higher prices.

Second, the National Cabinet intends to construct 240,000 dwellings every year, or 660 units per day. But Australia has only ever built more than 220,000 dwellings in a single year once, in 2017, when it built 223,000.

Australia’s 40-year average home construction pace is only 160,000, which is 80,000 fewer than the aim set by the National Cabinet.

So, how will Australia build more homes than ever before in the face of widespread building failures, material and labour shortages, and higher interest rates?

Third, what about the infrastructure required to support this increased homes and population? Most of our main capital cities’ highways, schools, and hospitals are already at capacity.

Finally, even if we could suddenly create these 1.2 million homes, they would almost certainly be of poor quality.

The preceding decade’s development boom was accompanied with widespread flaws such as cracks, water leaks, and balcony defects (e.g., Sydney’s Opal and Mascot Towers).

Building so many apartments as quickly as National Cabinet intends will unavoidably reduce quality, resulting in the same types of structural problems we saw last decade.

The solution to Australia’s housing shortage is on the demand-side:

The primary cause driving Australia’s housing shortage is not a lack of construction capacity. Rather, Australia has one of the world’s largest immigration program, ensuring that housing demand always exceeds supply.

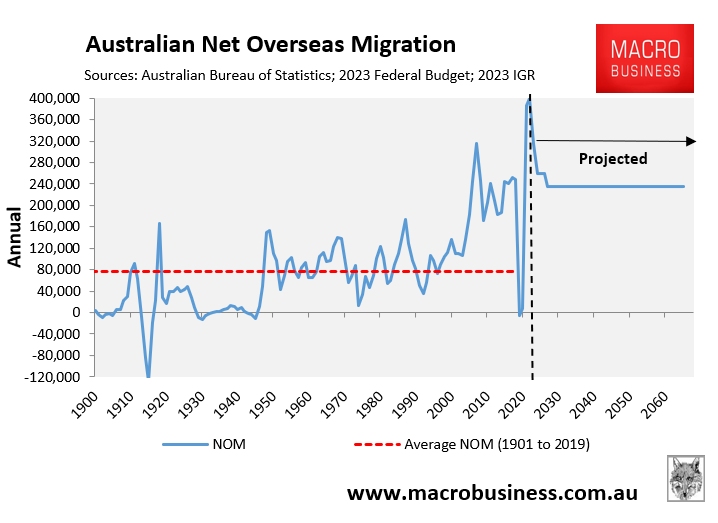

Australia’s net overseas migration (NOM) averaged 96,000 people per year from 1992 to 2002, whereas population growth was 216,000 people per year.

Australia’s NOM averaged 190,000 in the 20 years through 2022, and population growth averaged 328,000 people each year. This time period included the pandemic-related negative NOM:

Australia’s population has expanded by 7.4 million people (39%) this century, the nation’s biggest population rise on record.

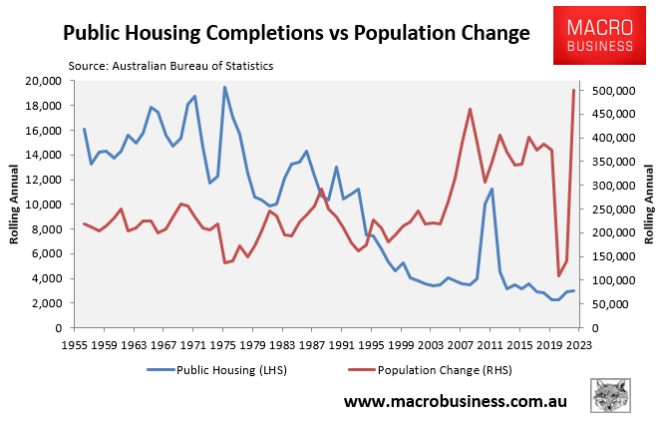

This rapid population growth, along with decreased investment, has exacerbated the public housing shortfall to crisis proportions:

Australia supplied approximately one public home for every 12 to 30 new Australians between 1955 and 1993.

In the decades that followed, the ratio of public housing to new Australians declined to a low of one home for every 168 new Australians in 2022.

From here, the housing situation will only worsen.

The latest federal budget forecast that Australia’s population would grow by 2.18 million people (equal to the population of Perth) over the next five years, owing to 1.5 million net overseas migrant arrivals (similar to the population of Adelaide).

According to the recently released Intergenerational Report (IGR), Australia’s population will reach 40.5 million by 2062-63, propelled by a long-term NOM of 235,000 a year.

This means Australia’s population will increase by 14.2 million over the next 40 years, comparable to adding a combined Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide to Australia’s existing population of 26.3 million.

How will Australia’s housing supply ever keep up with demand if the population is expected to expand by 355,000 people each year for the next 40 years?

Over the last two decades, Australia has not built enough dwellings. Although the rate of home construction increased to record levels last decade, it was unable to keep up with the enormous increase in immigration-driven population growth that began in the mid-2000s:

What makes anyone think we’ll get better results in the next 40 years?

Furthermore, do Australians wish to live in high-rise apartment buildings? Because, with a population of 40.5 million and Sydney and Melbourne each having nine million people, this will become the norm.

The same charges can be levelled about Australia’s infrastructure, which has been massively overburdened by the 7.4 million population increase this century.

How will Australia make up for its cumulative infrastructure deficits in roads, public transportation, hospitals, and schools, let alone provide adequate infrastructure for an additional 14.2 million people? It’s a hopeless task.

It’s all about immigration:

The housing shortage in Australia is a direct outcome of nearly 20 years of excessive immigration, which the IGR predicts will continue for at least another 40 years.

If the Albanese Government truly desired to address the country’s housing deficit, it would operate an immigration program that was significantly lower than overall increase in the housing stock, not the other way around.

It’s time to stop blaming a ‘lack of supply’ and start addressing the immigration elephant at the centre of Australia’s housing shortage.