Australian Treasury Secretary, Dr Steven Kennedy, gave a speech this week to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia where he gave a comparison of the results from the 2002 Intergenerational Report (IGR) and the 2023 IGR, released in August.

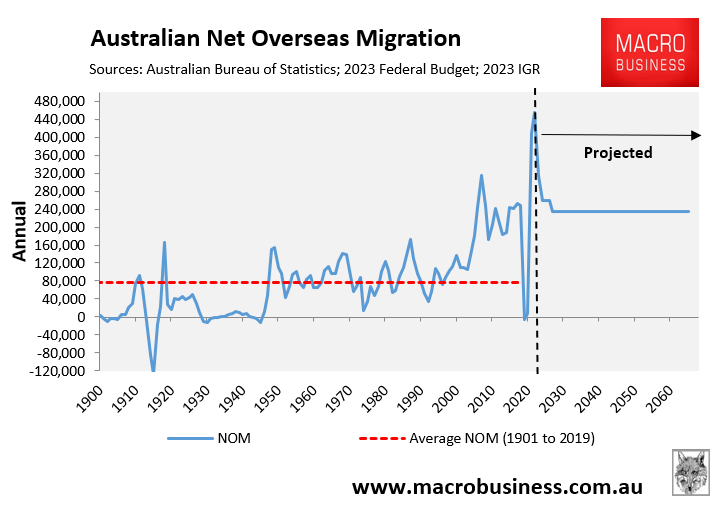

Kennedy noted that Australia’s population is significantly larger and younger than forecast in the 2002 IGR courtesy of the ramp-up in net overseas migration that has occurred over the past 20 years:

“Australia’s population is larger and younger than was projected in the 2002 IGR. The 2002 IGR projected population to reach 25.3 million in 2042, but this was surpassed in 2018–19”.

“Higher migration has been the primary driver of the larger and younger population compared to the 2002 IGR”.

“The 2002 IGR assumed net overseas migration of 90,000 persons per year. Instead net overseas migration, between June 2002 and June 2022, averaged around 200,000 persons per year”.

“The main reason for this increase was successive increases in the permanent Migration Program from around 108,000 persons in 2002‑03 to 190,000 by 2012‑13”.

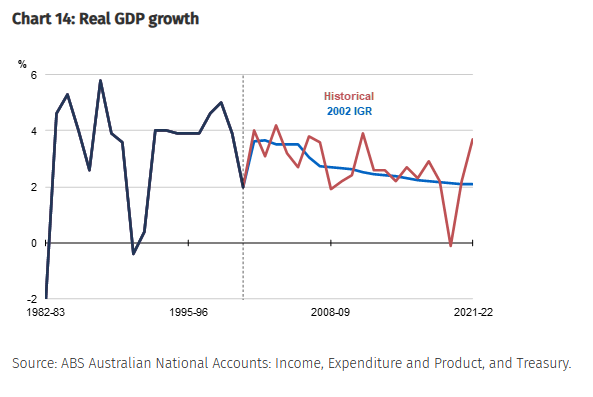

Kennedy also claims that actual economic outcomes have been broadly similar to those projected in the 2002 IGR:

“Despite the significantly different outcomes in productivity, population and participation, the aggregate position of the economy and the shares of tax and expenditure at the end of the period have ended up close to the 2002 projections”.

“Real GDP grew by a total of around 70% between 2002 and 2022, compared to 69% projected”.

“A remarkable outcome given that:

- “Productivity was much lower than expected, averaging 1.2% per year compared to 1.8% projected”

- “The population was much higher (around three million or 12%) than projected, driven by net overseas migration around double what was assumed”

- “Participation was much higher, at 66% in 2021–22, compared to around 60% projected”.

“Finally, nominal GDP was stronger than expected, in part reflecting the mining boom’s boost to the terms of trade which is now well above the long-term average”.

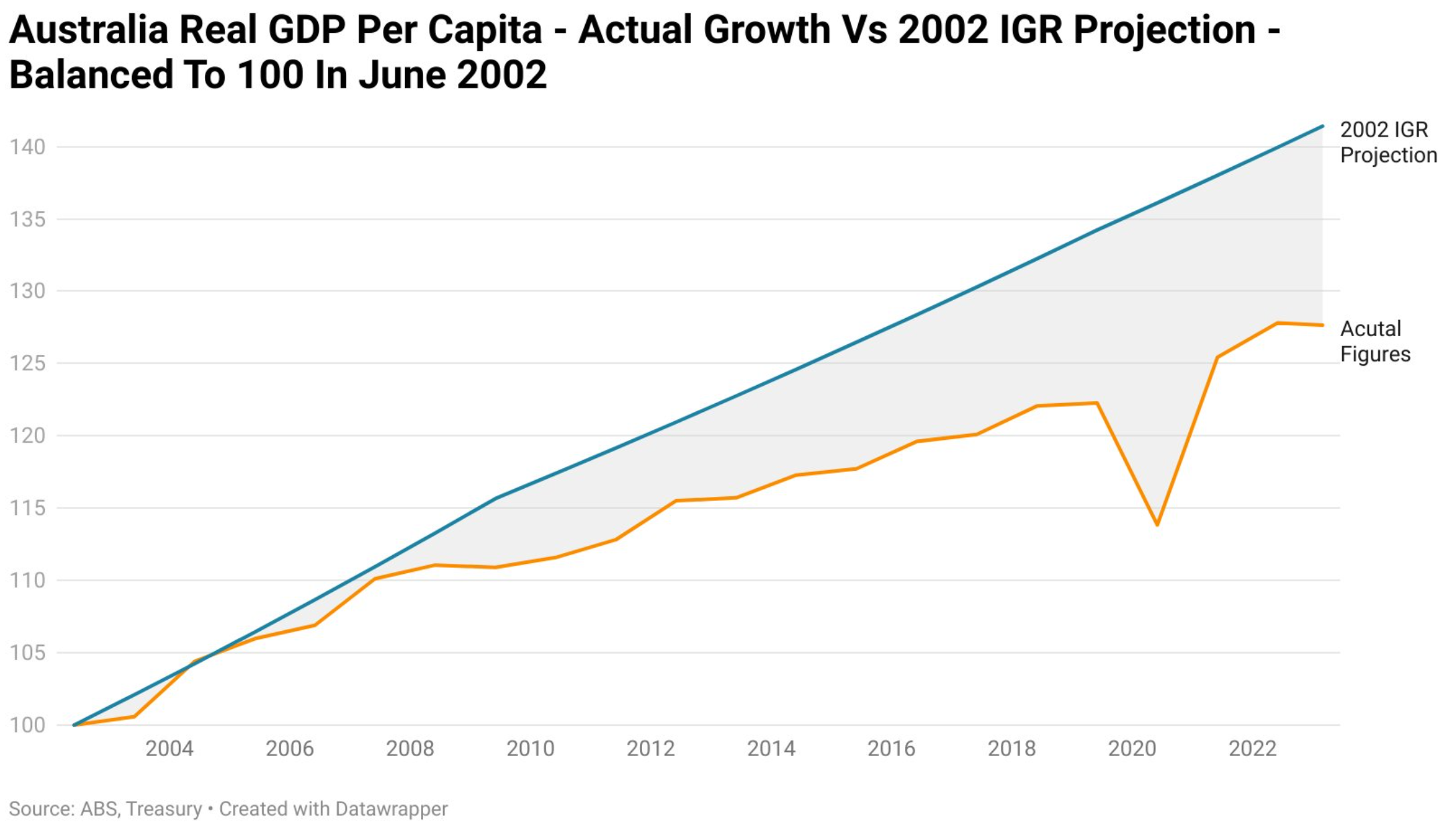

Conveniently, Kennedy has chosen to present the GDP data in aggregate terms. Because if he had presented it in per capita terms, it would have shown how Australia’s actual performance has badly lagged the 2002 IGR:

Source: Tarric Brooker

As noted by independent economist Tarric Brooker recently, that’s “a pretty striking shortfall considering we had a mining and LNG boom buff out the numbers”.

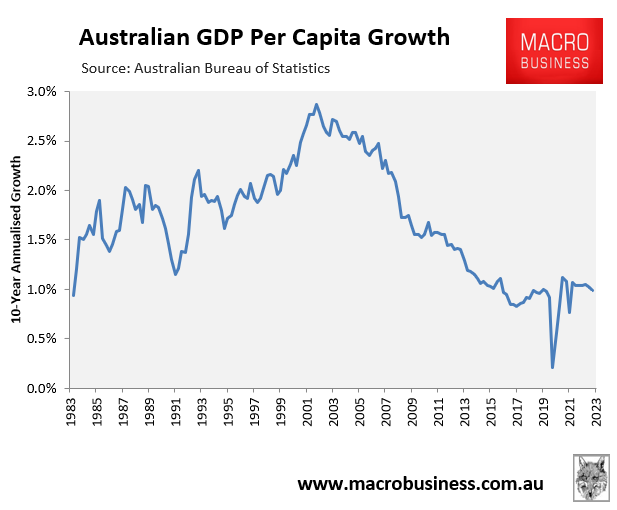

This stronger population growth kept the aggregate size of the economy growing at a respectable rate, while per capita growth plunged:

Australia’s per capita GDP grew strongly at the start of the century as the mining boom took off. But after that, growth has evaporated.

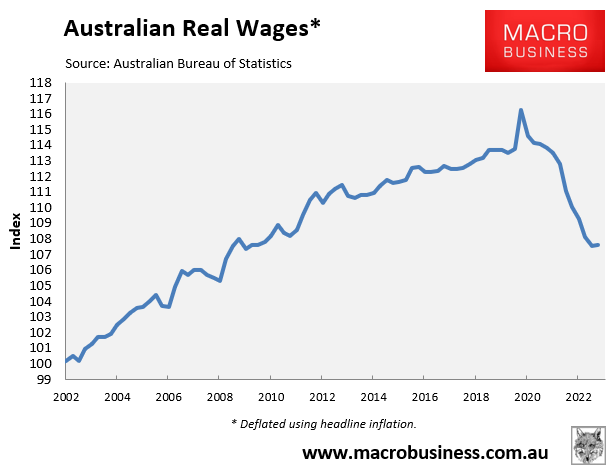

It is the same story for Australian real wages, which have recorded minimal growth this century:

The situation is unlikely to change given the federal government has chosen mass immigration-driven population expansion as the economy’s main driver:

The 2023 IGR projects that Australia’s population will expand by 14 million people in only 40 years – equivalent to adding a combined Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide to the current population.

While this enormous population increase will grow the economy’s GDP, everybody’s slice of the economic pie will stagnate as broader living standards are crushed under the endless population deluge hitting infrastructure, housing and the natural environment.

It is a recipe for a lost century for Australians.

As usual, the Treasury prefers to hide the reality from Australians.