Australian importers and overseas tourists may be wondering what they have done to deserve a relentlessly falling Australian dollar this year.

In truth, the currency has been beaten down for more than ten years:

Why? We can deduce the answer by comparing the futures of our two big and powerful allies and trade partners, the United States and China.

After the 2002 Chinese accession to the WTO, AUD closely mirrored the ups and downs of China’s catch-up growth.

Chinese growth was driven by taking factories from developed countries. However, its investment in modern infrastructure relied heavily on Australian commodities. As a result, the Australian dollar rose dramatically against other developed markets.

This led to the crazy AUD peak at $1.11 in 2012. A point of extreme hubris known colloquially as the “Australian moment”. A “moment” was right.

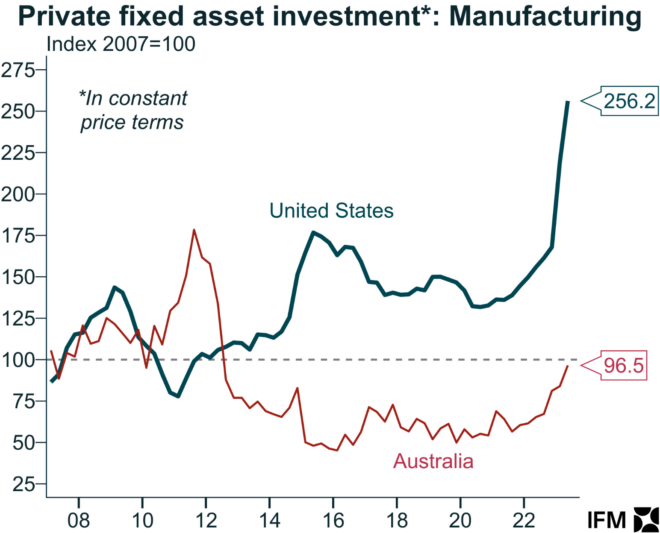

Since 2012, the underlying trends of China’s rise began to reverse. Its competitiveness waned and DMs began to rebuild lost industries:

This, in turn, increased growth and, eventually, other DM currency values through increasing productivity and labour share of revenue.

On the other hand, Australia prioritised population growth through immigration over restoring its production base.

This put pressure on per capita national income and salaries. It reduced to a crawl growth in per capita output because of capital shallowing. Australian machines, infrastructure and other hard capital were spread among an ever-expanding population producing less with more.

Why use an automated carwash when you can use twenty underpaid workers to wipe it down?

These policies are currency negative. They keep inflation and interest rates lower than elsewhere and suppress labour’s share of income.

So, is the AUD low enough? Very likely not.

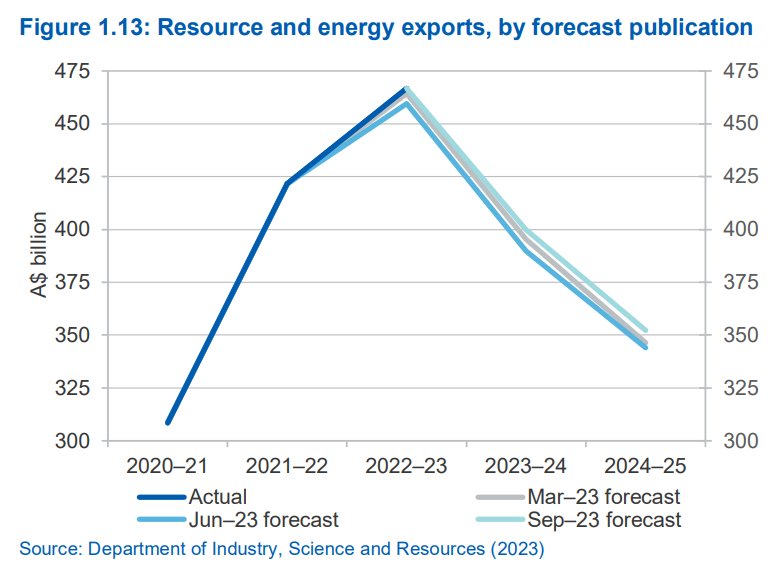

The massive shift in global power has not yet concluded. Chinese growth has entered a structural decline in growth, most especially in its commodity-centric construction sector. As the four “Ds” – demographics, deglobalisation, deleveraging and dictatorship – stall China’s rise, Aussie commodities will fall much further yet.

The Office of the Chief Economist, which is responsible for commodities forecasting for the Australian government, is not holding back:

On the other side of the geopolitical coin, momentum is building for a new wave of growth in US manufacturing. Its IT companies have taken the lead in AI, ensuring a continued infusion of capital into high-end, value-added industries.

These two factors continue to press against the Australian dollar. And, if worse comes to worst, markets may be pricing in a confrontation between the two, with slowing Chinese development leading to increased aggression and the United States’ robust industrial capacity repelling the threat.

In effect, forex markets are encouraging Australia to diversify its industrial base as the relative risk of competing superpowers shifts.

However, Canberra refuses to accept “yes” for an answer and instead keeps using quantitative peopling to prevent any recovery in production.

Property-addicted politicians may need an AUD in the 40s before they get the message.