The past 18 months under the Albanese government have been a financial nightmare for Australian households, which culminated in Australia breaking three global records for declining living standards.

The first of these records pertains to the disposable income of Australian households, a concept that is arguably the most accurate indicator of material living standards.

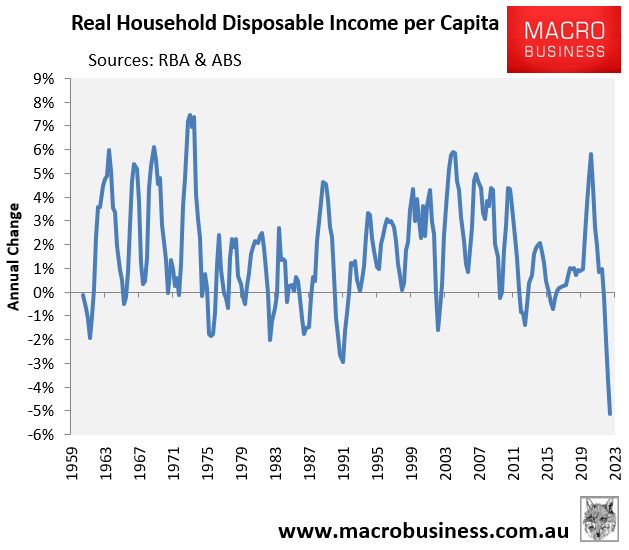

According to the most recent national accounts published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), real household disposable income plummeted by 5.1% during the 2022-23 financial year, which was the largest annual decline in recorded history:

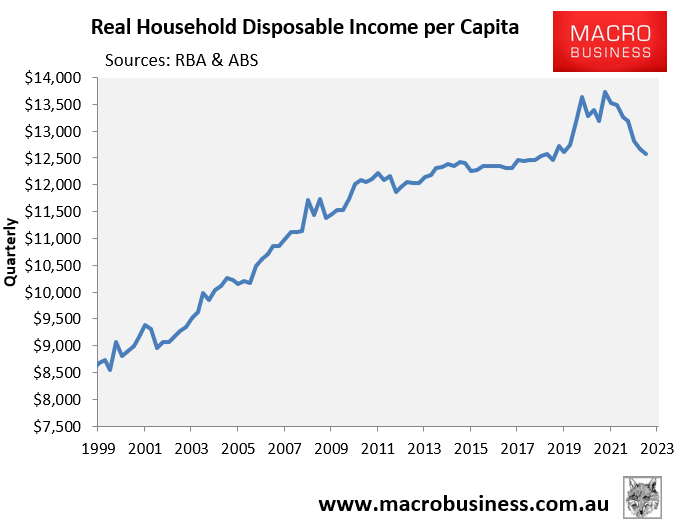

As a consequence, Australian households forfeited all the income gains generated by the stimulus measures deployed during the Covid-19 pandemic:

The real per capita disposable income of Australian households declined to levels last recorded in early 2019, which were only marginally higher than in 2010.

Thus, Australian households have experienced negligible income growth over the past thirteen years.

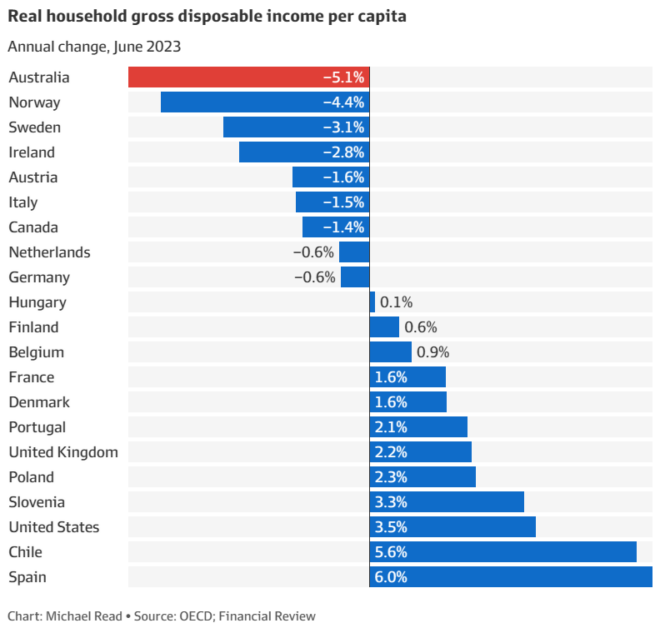

Using OECD data, Michael Read from the AFR analysed how the decline in Australia’s real per capita household disposable income compares internationally:

Last financial year, Australian households experienced the largest decline in income globally, according to Read.

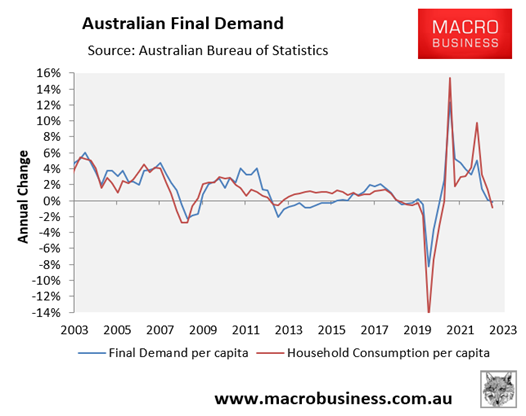

This decline in disposable household income contributed to a 0.2% decline in real per capita household expenditure in 2022-23, which in turn has cratered the nation’s economic growth:

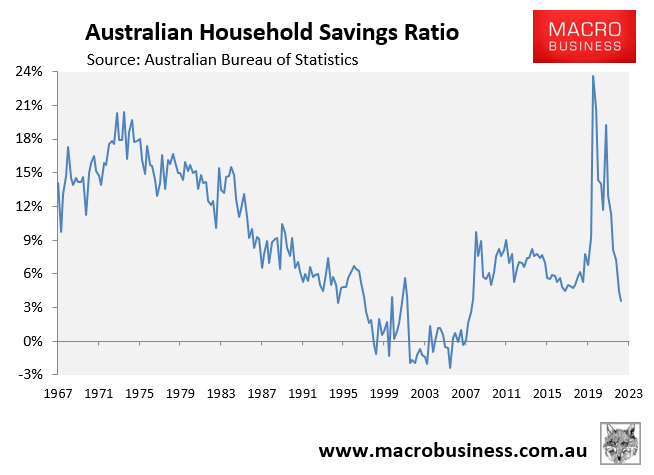

Had the household savings rate not declined to its lowest point since the June quarter of 2008, which helped bolster spending in the face of falling incomes, the outcome would have been more severe:

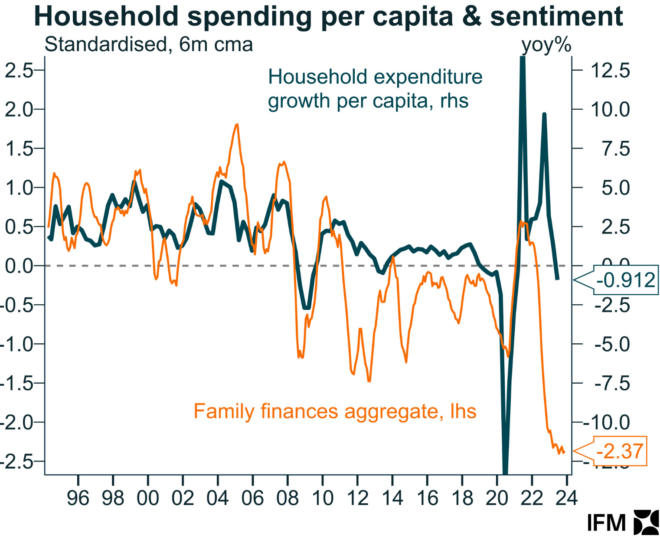

The following chart, compiled by Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors, illustrates the relationship between per capita household expenditure and the family finances subcomponent of the most recent consumer sentiment survey by Westpac:

Source: Alex Joiner (IMF Investors)

Family finances are clearly in the doldrums, which foreshadows additional per capita household expenditure declines in the coming period and the continuation of Australia’s per capita recession.

The worst rental in the world?

This brings us to the second broken record by Australia that signifies falling living standards.

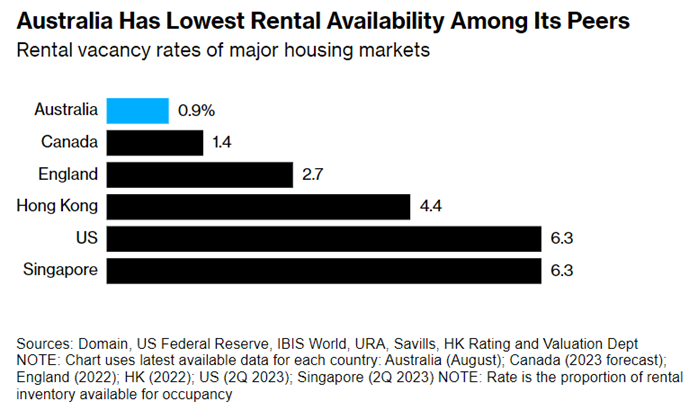

According to a report published by Bloomberg, Australia has the lowest rental vacancy rate out of the surveyed nations, at only 0.9%:

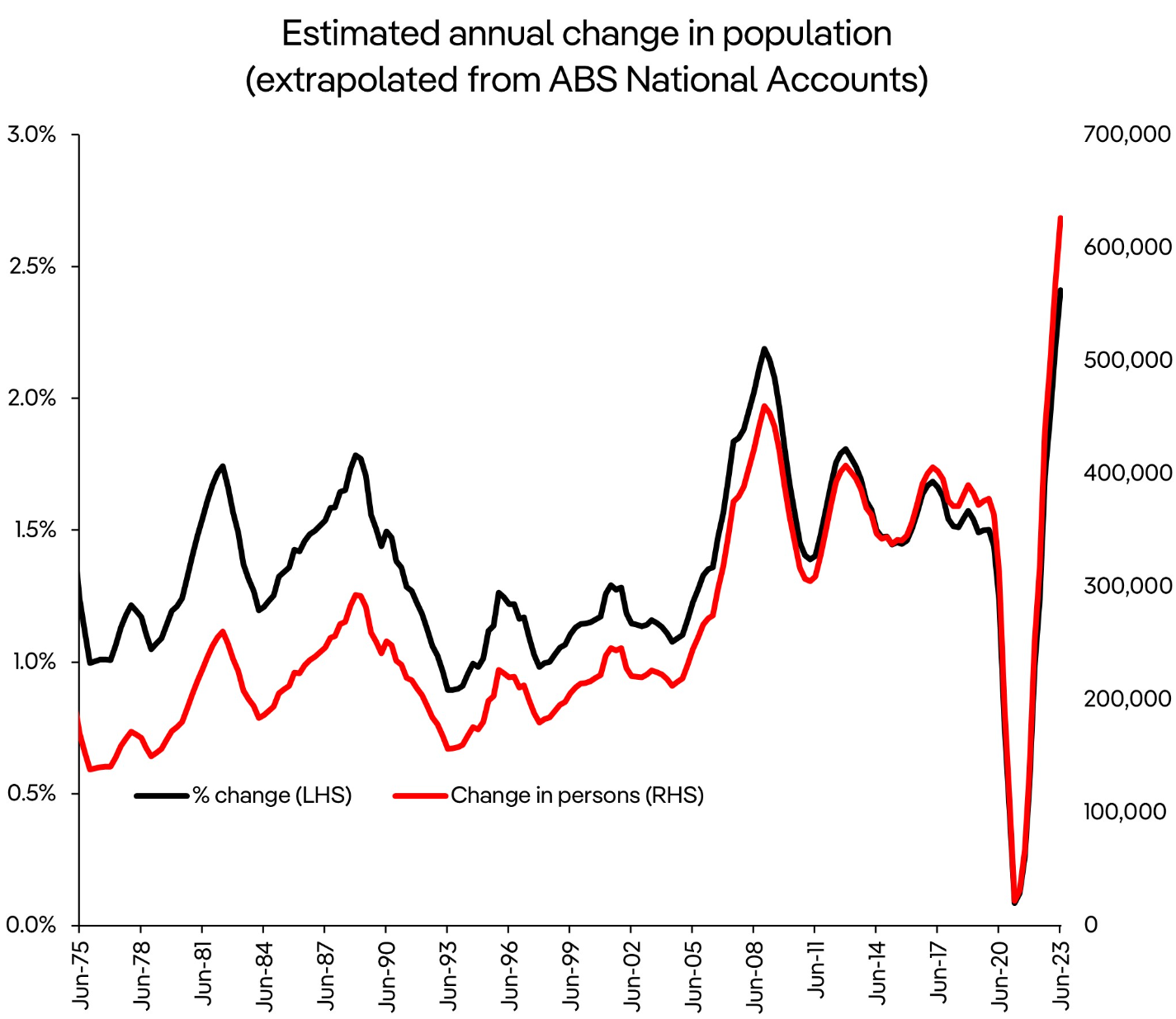

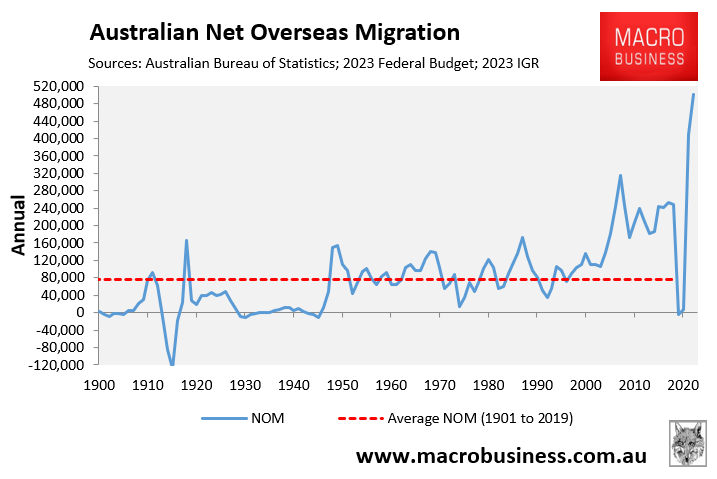

Australia’s rental vacancy rate has declined in the wake of unprecedented net overseas migration and population growth, with the country’s population increasing by over 600,000 people in the most recent financial year, according to the June quarter national accounts:

Source: Cameron Kusher (PropTrack)

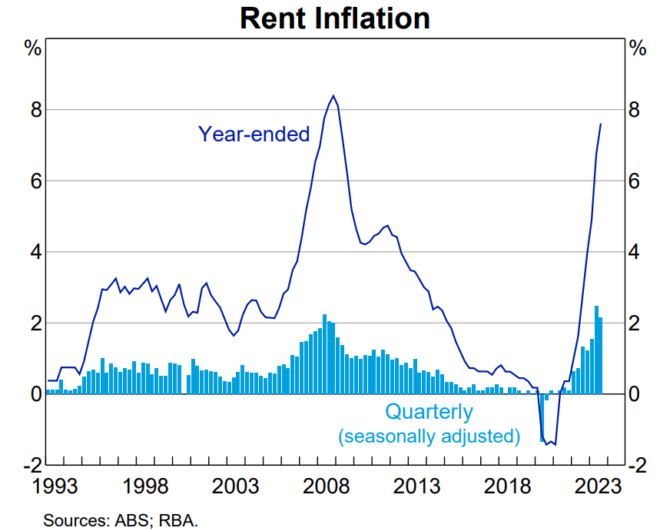

This population explosion, coupled with tight rental supply, has caused rental inflation in Australia to soar, in turn contributing to an increase in CPI inflation as a whole:

“High rent inflation has been broadly based, consistent with tight rental market conditions across the country. Housing supply has not kept pace”, the RBA noted in its latest Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP).

“Advertised rents have increased 30 per cent since prior to the pandemic, much more than the increase in CPI rents so far”.

“Together with historically low vacancy rates, and little sign that tight rental market conditions will ease in the near term, this is expected to keep rent inflation elevated for some time”, the RBA SoMP warned.

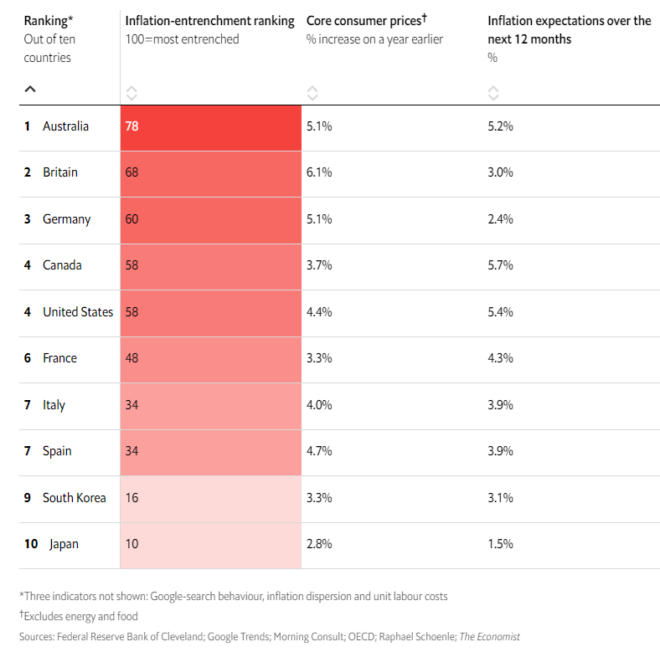

Inflation is “entrenched” in Australia:

Australia was also this month ranked number one for entrenched inflation by The Economist magazine, in part due to its robust rental growth:

The Economist’s “entrenched” inflation measure is based on an assessment of actual inflation and inflation expectations, with Australia ranking poorly on both fronts.

Further suffering awaits Australian households:

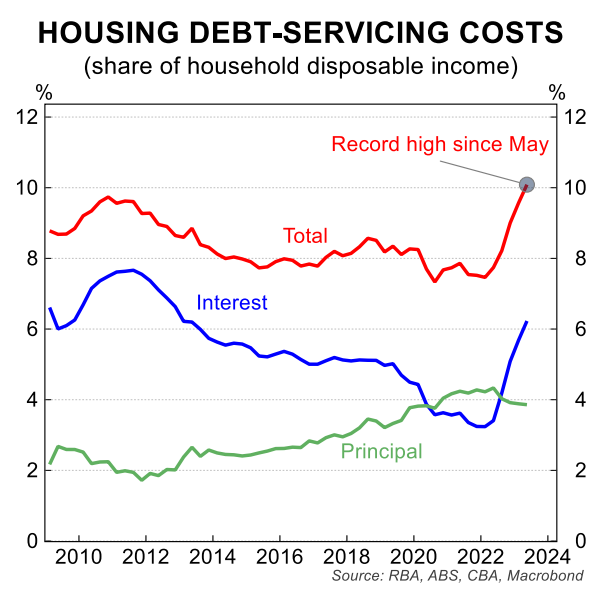

In light of the fact that housing debt servicing costs had already reached all-time highs prior to the RBA’s interest rate increase this month, the outlook for Australian households remains bleak.

The debt repayment burden will increase further as a result of the RBA’s latest 0.25% rate hike and the continued expiration of cheap pandemic fixed-rate mortgages.

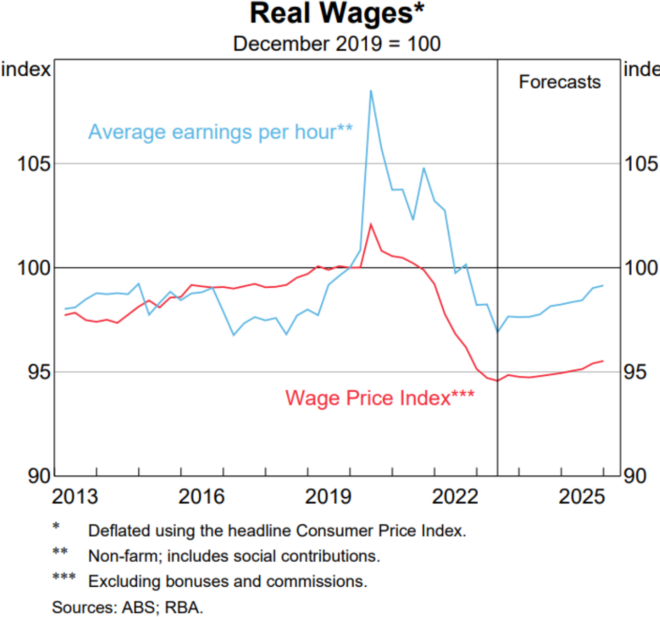

Meanwhile, the RBA SoMP projects that real wages in Australia will continue to remain below pre-pandemic levels for years:

Australians are confronted with an extended period of declining living standards brought about by: a severe per capita recession; falling real wages, incomes and productivity; escalating mortgage repayments and rents; and overburdened infrastructure and services.

Never before have we seen a federal government wreck living standards so fast, driven by unprecedented levels of net overseas migration that is crush-loading everything in sight, pushing up living costs and inflation, and forcing the RBA to respond with higher interest rates.

If the Albanese government genuinely wanted to address the housing crisis and inflation, it would reduce net overseas migration to a level that is below the nation’s capacity to provide housing and infrastructure, rather than running immigration at record levels.