Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) senior fellow, Kevin You, has undertaken an analysis of Australia’s competitiveness using data from the respected International Institute for Management Development (IMD) World Competitiveness index.

You found that Australia fell from the most resilient economy in the world in 2004 to 20th today.

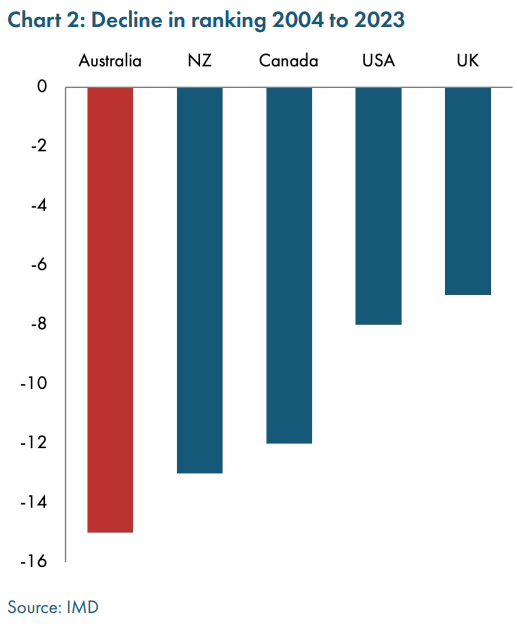

Australia’s ranking also plummeted 15 places on economic competitiveness – the largest decline among comparable nations, including the US, UK, Canada, and NZ.

Below are key extracts from the report.

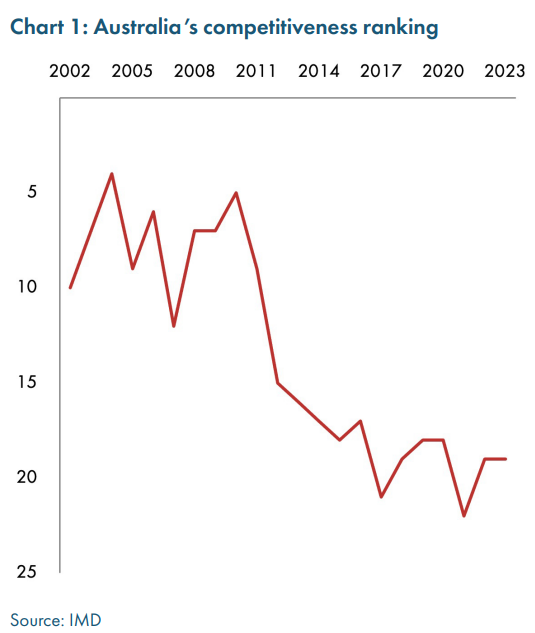

“In the 2000s, Australia consistently ranked as one of the most competitive economies in the world. But in recent years, Australia’s economic competitiveness has fallen behind”.

“In 2023, Australia ranked 19th, just behind the Czech Republic and Saudi Arabia—and far behind regional trading partners such as Singapore, Taiwan, and the United States (US)”.

“Australia has seen a significant drop in its World Competitiveness Ranking since the 2000s. In 2004, Australia was ranked the 4th most competitive economy in the world, behind only the US, Singapore and Canada”.

“Australia is now ranked 19th overall. Over the last 20 years, the rankings of several other advanced economies have also worsened. But Australia’s decline from 4th to 19th has been more severe than the decline of comparable nations”.

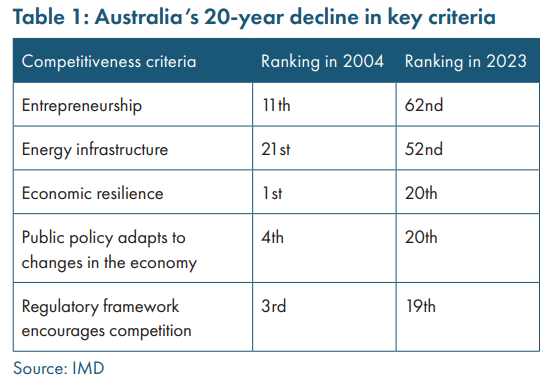

“Among a selection of key criteria, which are critical to economic competitiveness and dynamism, Australia’s standing in the world has undergone a significant twenty-year decline”.

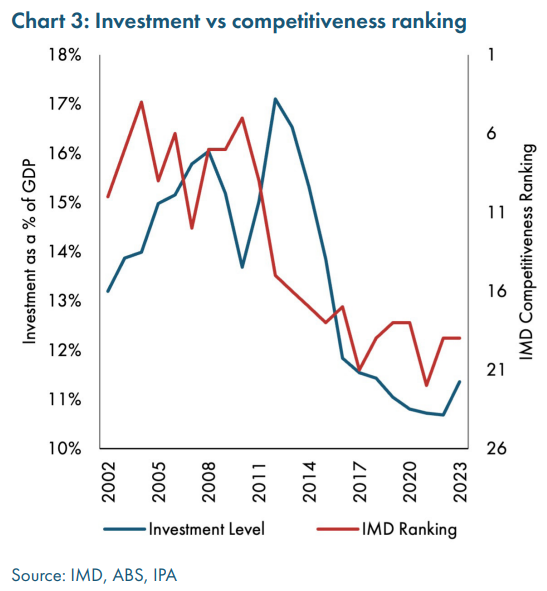

“Australia’s continuing decline in overall competitiveness is a key reason why business investment has been floundering in recent years”.

“Since 2017, private investment in Australia has been stuck below 12% of GDP, hovering just above its historic low of 10.15% in the September quarter of 1992”.

“The change in Australia’s level of private business investment has tracked consistently with its declining competitiveness ranking over the same period”.

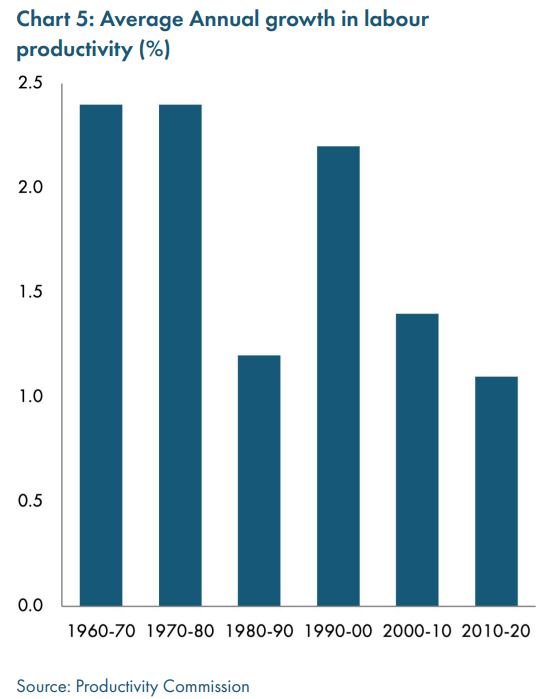

“These low rankings are consistent with a recent study by the Productivity Commission, which found labour productivity in Australia having decreased by 4.6% between April 2022 and March 2023”.

“To put this into context, annual labour productivity growth in the two decades between 1960 and 1980 was positive 2.4% per annum. In the 1990s, it averaged positive 2.2% per annum”.

“Between 2010 and 2020, labour productivity averaged positive 1.1% per annum”.

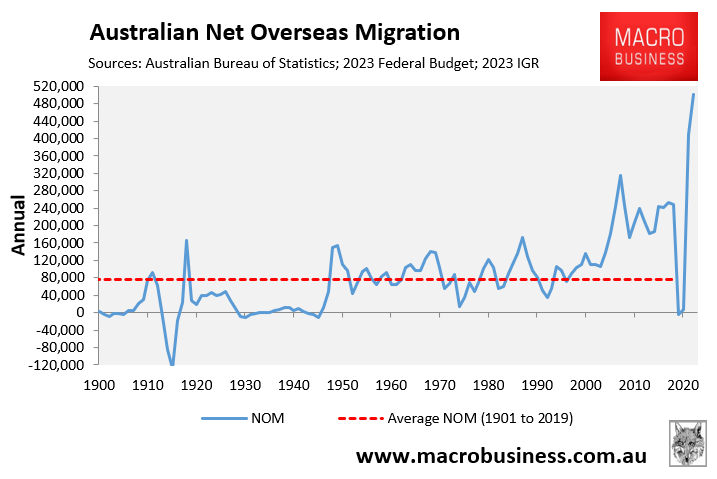

Hilariously, the decline in Australia’s competitiveness has coincided with the massive ramp-up in net overseas migration (NOM) beginning in 2005:

Vested interests argue that a strong migration program boosts productivity because migrants are supposedly better educated, earn more and are more highly skilled than local workers.

The reality is that migrants work and earn less on average than locals, have higher unemployment rates, and are also older on average. That’s why you typically see them driving Ubers and performing other low-skilled jobs.

Moreover, when infrastructure, housing and business investment fails to keep pace with population growth and becomes more expensive through dis-economies of scale, then productivity stalls – as it has in Australia this century.

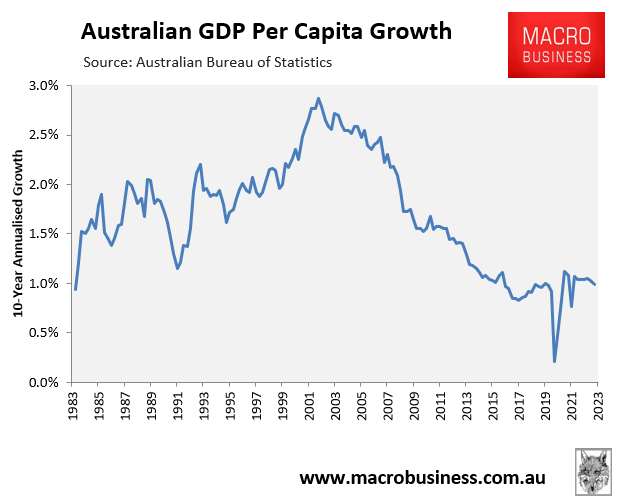

If immigration was such a boon for productivity, then why did Australia’s per capita GDP collapse after the immigration floodgates were opened in 2005 despite the biggest ever mining investment boom?

The empirical evidence is clear.

There are many negative externalities arising from high immigration that are rarely considered by vested interests, policy makers or economists.

These include:

Environmental impacts, as laid out in the 2021 State of the Environment (SoE) Report: “most population-driven pressures are considered to be high or very high impact, and increasing… Population growth contributes to all the pressures described in this report”:

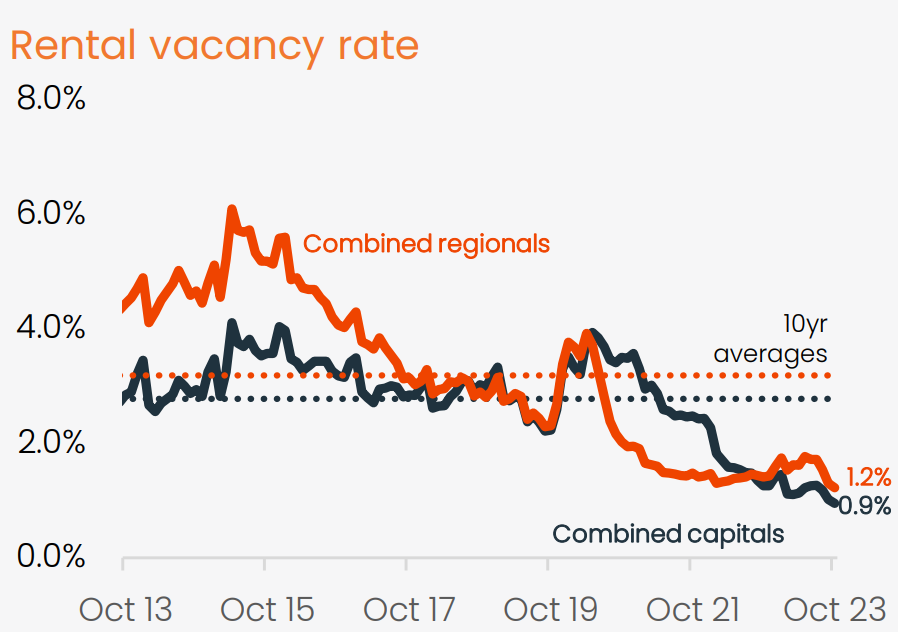

Housing impacts, including the rental crisis and having to live in smaller and more expensive homes:

Source: CoreLogic

Having to build expensive, energy-guzzling desalination plants because we have insufficient water supplies for the expanding population.

More congestion and higher user costs because infrastructure never keeps up and becomes more expensive when cities have to retrofit to sustain larger populations.

Less access to open spaces and heat island effects as trees and gardens are chewed up for housing.

The list goes on.

Nobody denies that a moderate level of MOM is beneficial.

However, for nearly 20 years Australia has run an immigration program that is way beyond an optimal level, causing widespread housing and infrastructure shortages, alongside lower productivity and living standards.