Last week’s Commbank IQ data on spending was an eye-opener and would no doubt be causing headaches within the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

On Wednesday night, RBA governor Michele Bullock told the Australian Business Economists dinner that Australia’s inflation is “increasingly homegrown and demand driven”, and “an indication that aggregate demand is sufficiently greater than aggregate supply”.

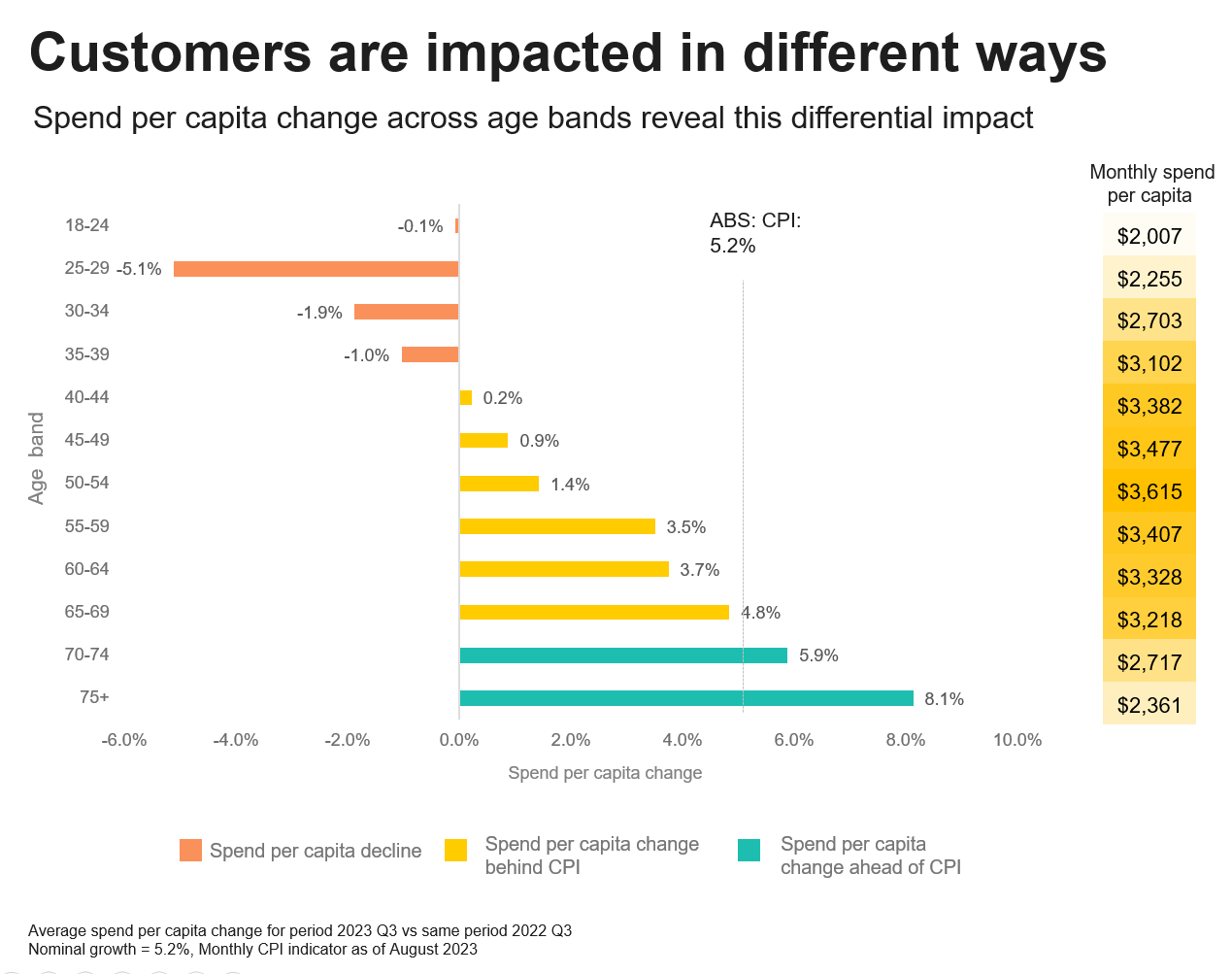

This prognosis followed shortly after Commbank IQ released data on spending by age cohorts, which showed that older Australians are spending freely, while younger Australians are cutting back hard on consumption:

As shown by the green bars above, older Australians aged 70 or above increased their spending by more than the rate of inflation in the year to September 2023, whereas younger Australians under the age of 40 cut their spending in absolute terms (orange bars), while everyone else increased their spending by less than inflation (yellow bars).

Amazingly, Australians aged between 65 and 74 also spent more in September than Australians aged 30-34.

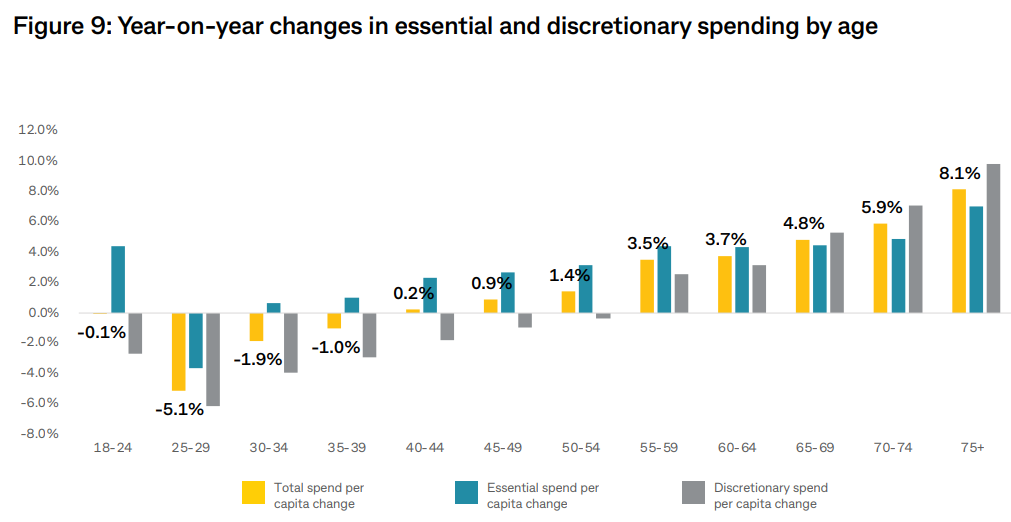

To add further insult to injury, older Australians are spending most on discretionary items, whereas younger Australians are cutting back hard on both discretionary and essential spending:

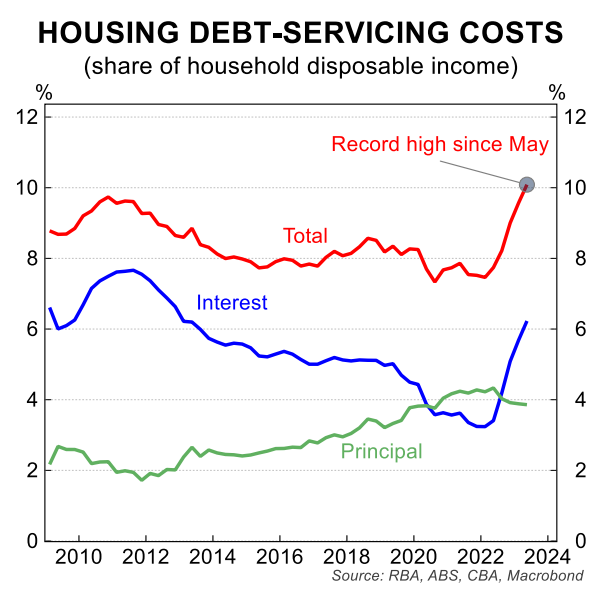

The above data is worrying from a monetary policy perspective, given older Australians are largely immune from the RBA’s aggressive monetary tightening, which only directly impacts around one-third of Australians with mortgages.

In fact, many older Australians are benefiting from higher interest rates on deposits. Older Australians on the aged pension are also insulated from high inflation, since their benefits are automatically indexed to CPI.

This has left the RBA in a position where it is smashing one-third of Australians with mortgages in an attempt to slow demand and inflation, while older Australians are busy stimulating demand via their profligate spending.

In turn, the RBA will be forced to respond with even higher interest rates, which will further harm younger Australians.

The data is clear: curbing inflation hinges, in part, on lowering the spending of baby boomers, not smashing younger Australians, who have already cut back hard.

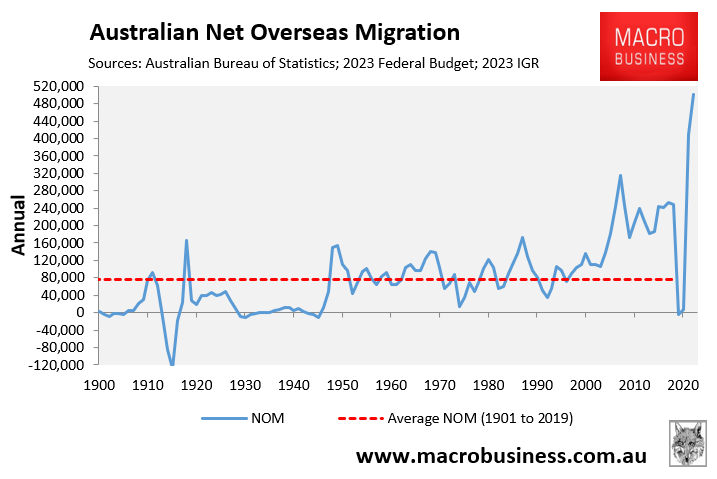

It also requires the federal government to stop importing consumers via record levels of net overseas migration.