The AFR published an article last week arguing that profligate spending by younger Australians is “driving up inflation”, forcing the RBA to lift rates higher:

Retired academic Michael Valos and his adult children’s differing financial aspirations are widening a generational divide that is making it tougher for the Reserve Bank of Australia to beat inflation.

“The younger generation is living more in the moment,” says Valos. “Their attitude is: ‘Stuff it, let’s spend it now’. This is a generation that expects to go to restaurants, that expects to travel,” he says.

The irony is their combined spending continues to drive up inflation, which makes the Boomers more secure from rising saving rates and their children less able to afford a property because of increased funding costs.

The data does not support this contention. If anything, it shows that the spending habits of baby boomers are driving up inflation.

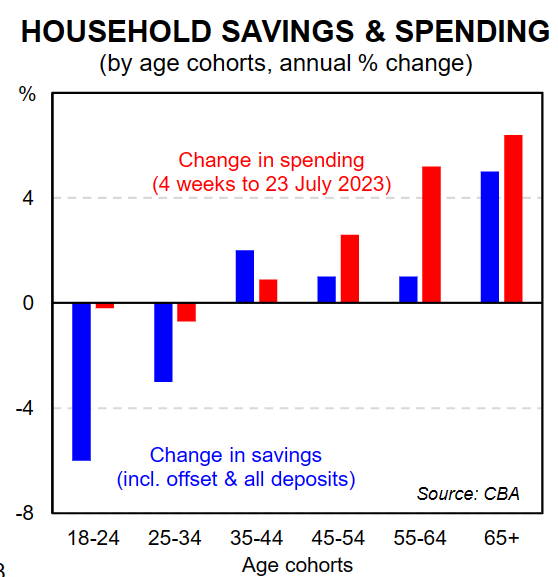

The below CBA chart shows the annual change in savings and expenditure across age cohorts in Australia:

As you can see, the savings of younger Australians have decreased, as has their consumption.

By contrast, both savings and expenditures among senior Australians increased over the year. This effect has been most pronounced among households aged 65 and older (i.e. the baby boomer generation).

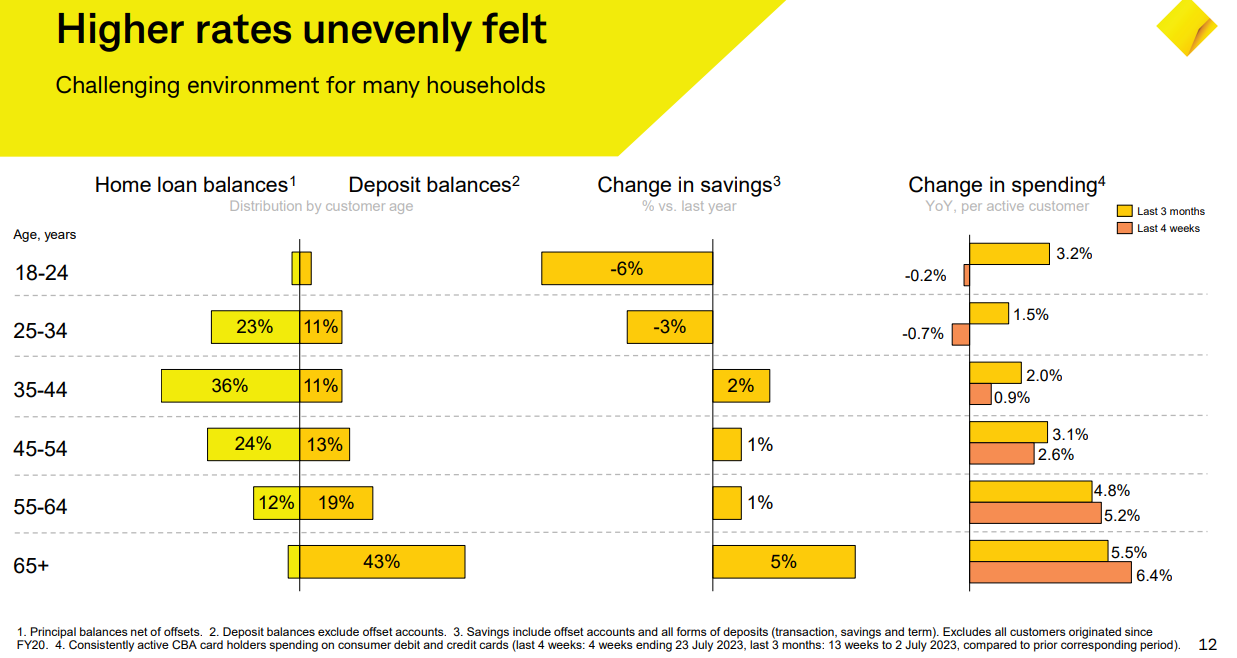

The adverse effects on younger Australians and the beneficial effects on older Australians resulting from the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) official cash rate increases were illustrated in the CBA’s latest investor pack:

Households aged 65 and above have modest mortgage debt and constitute 43% of the overall CBA savings.

Conversely, households between the ages of 25 and 54 have the highest mortgage debt and the lowest savings.

Households aged 65 and older also increased their spending the most during the previous four weeks (+6.4%) and the final three months (+5.5%) compared to the previous year.

By contrast, spending by households aged 18 to 34 fell in comparison to the same four-week period last year.

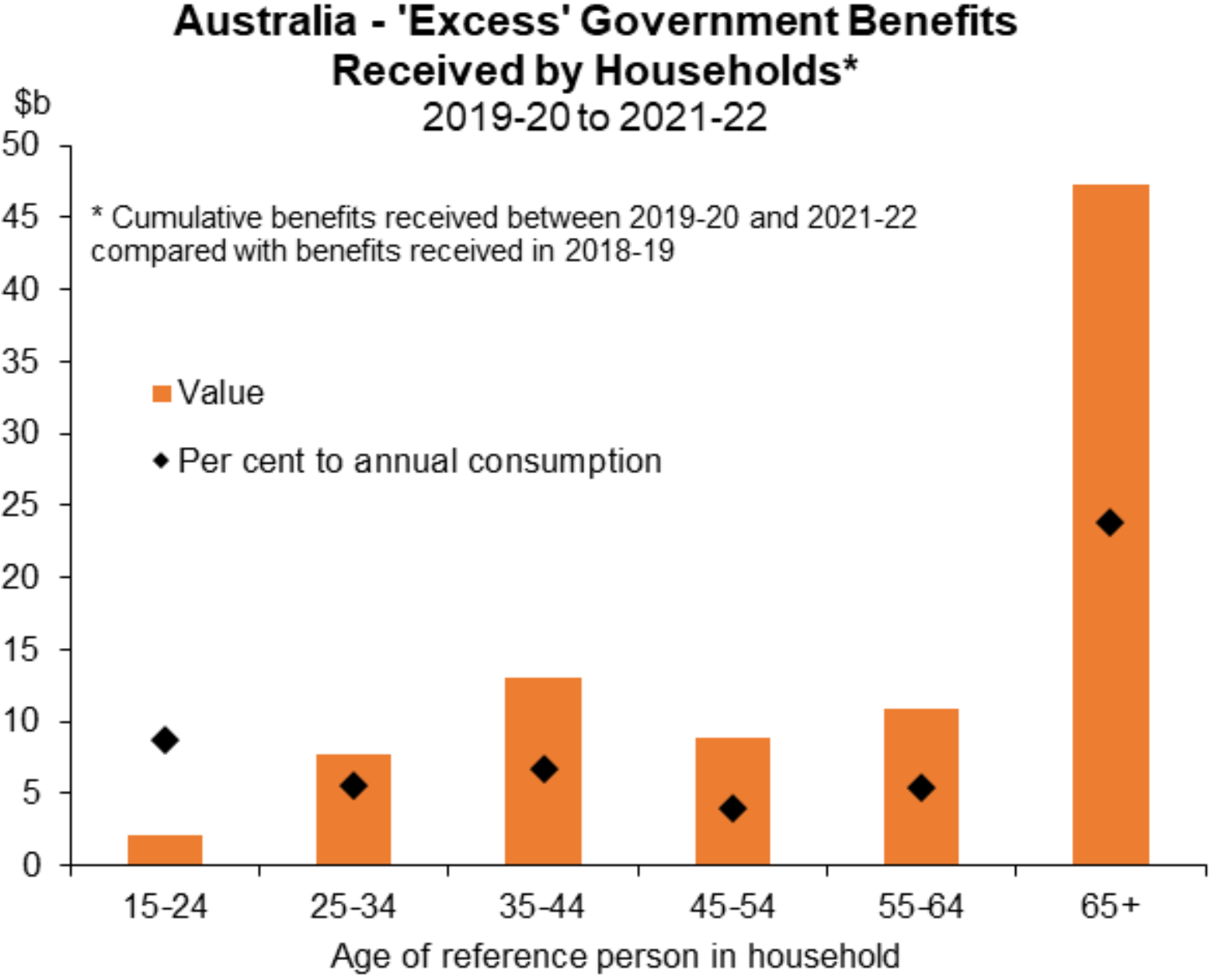

The inequity between generations is also present with regards to government subsidies and handouts.

An analysis of all subsidies provided by all levels of government, as measured by the ABS national accounts, was conducted by Macquarie Group’s Justin Fabo:

Source: Justin fabo (Macquarie Group)

As you can see, the lion’s share of ‘excess’ subisdies have gone to Australians aged 65 and over.

“Of the $85-90 billion in ‘excess’ government benefits paid to Aussie households over the 3 years to 2021-22, more than half went to households where the head was 65+ years old”, noted Fabo.

“Relative to what these households spend each year, it was huge”.

An element of this rise in subsidies for senior Australians relates to the expansion in eligibility for Commonwealth Seniors and healthcare cards following the 2022 election.

For instance, an additional 50,000 seniors were granted access to $6.80 prescription medications and additional discounts through the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card, which included self-funded retirees.

The income test threshold for individuals applying for the card was raised from $57,761 to approximately $90,000. Similarly, the threshold for couples was increased from $92,416 to $144,000.

The healthcare card is now eligible for discounts on electricity, petrol, public transportation, and free doctor visits, among other benefits, in New South Wales.

Pensioners also received an additional tourism discount in New South Wales during the pandemic, and their public transport fares remain fixed.

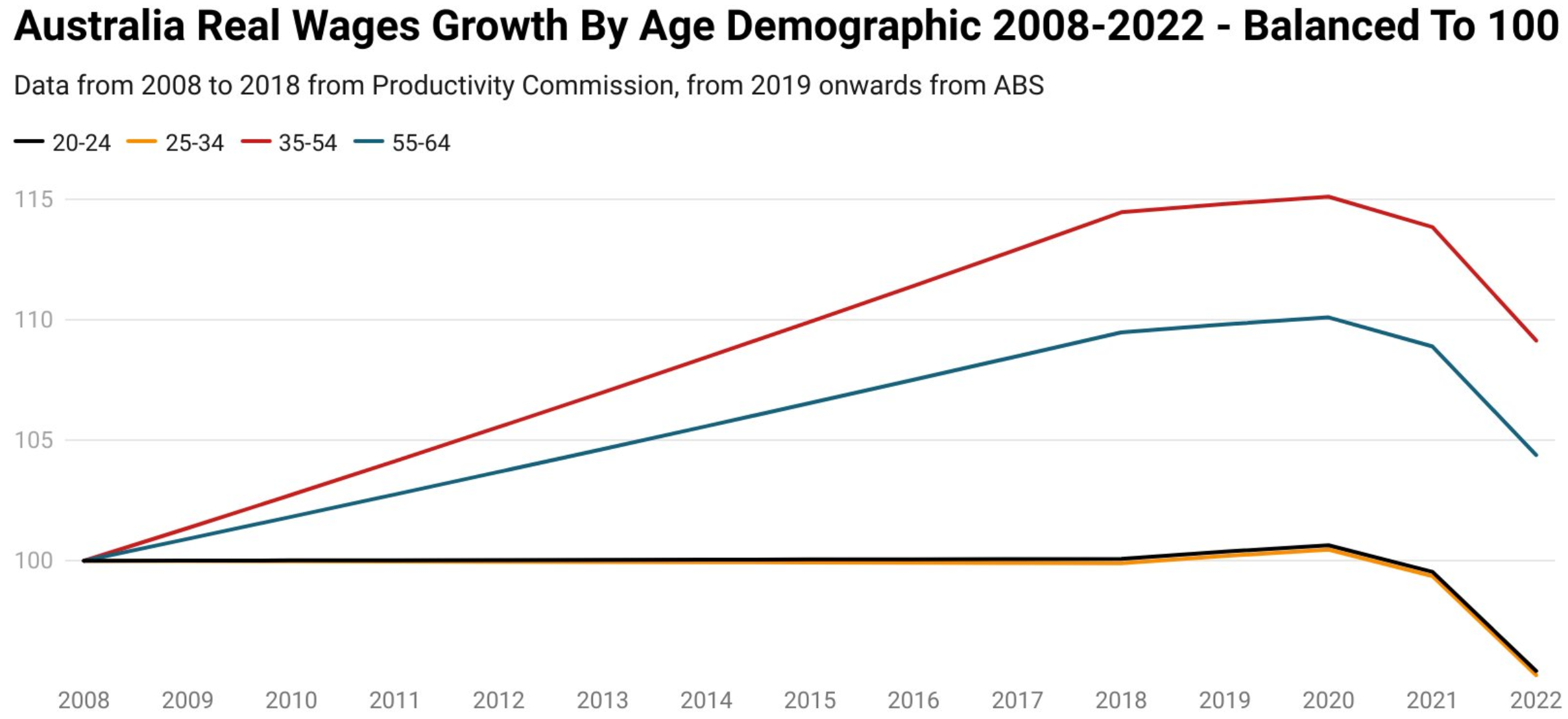

Finally, it is worth noting that the real wages of younger Australians have fallen over the past 15 years, unlike older Australians:

Source: Tarric Brooker

The RBA’s rapid interest rate hikes directly impact around one-third of mortgage-holding households, especially Generation X and Millennials with children.

Another one-third of (mainly young) renting households are being smashed by the fastest rental inflation on record, as well as declining real wages, which is reducing their discretionary incomes and spending.

By contrast, the older generations (led by baby boomers) mostly own their homes outright and are largely unaffected by soaring mortgage rates or rents.

The data is clear: baby boomer’s are driving the nation’s consumption.

Combined with rapid immigration, their spending has pressured the RBA to retaliate with higher interest rates to slow the economy, which negatively impacts younger Australians.

The AFR is dead wrong: controlling inflation hinges, in part, on curbing the profligate spending of baby boomers.