Recidivist China apologist, James Curran, is ecstatic about Albo China grovelling:

The prime minister’s arrival in Shanghai followed the script. His formula for managing relations has been long pre-packaged. Australia will “co-operate with China where we can” and “disagree where we must”, he said on arrival.

But the government’s flatline of “stabilisation” – a calibrated, necessary strategy for the moment – will inevitably come under strain. The Chinese side heralds the visit as a “new chapter” in relations, the Australians stick to manicured talking points about maturity. This pull between Chinese grandeur and Australian pragmatism will likely colour much of the visit.

This is NOT pragmatism. It is a following script only if one ignores the last ten years of Chinese aggression under Xi Jinping.

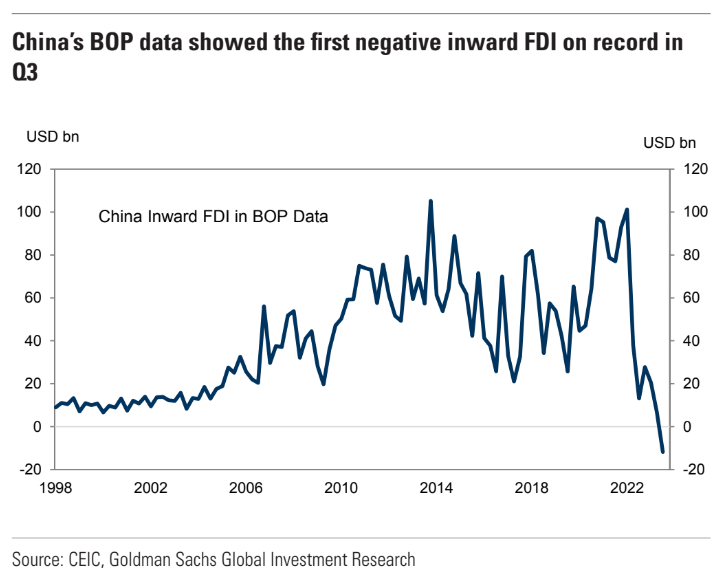

Other developed economies are not “following the script”; they are hedging their risk:

This is because the CCP has made it plain that it wants to occupy Taiwan, the COVID risk hangover, and Beijing’s record of interfering in domestic politics of developed economies, not least Australia.

All of these factors have led to a structural shift in the understanding of Chinese risk.

To ignore this takes a special kind of arrogance. The type of arrogance displayed by Paul Keating in the background of the ALP, Kevin Rudd in the foreground of policy thinking, and Albo in the vanguard.

The former doesn’t take much explanation. Keating is married to a residual Asian engagement that has long outlived its usefulness.

Kevin Rudd exercises a very unhealthy influence over ALP-China relations. From his perch in Washington, he has set about a vainglorious outcome of controlling both superpowers via his “managed strategic competition” thesis:

‘For policy makers in Beijing and Washington, as well as in other capitals, the 2020s will be the decade of living dangerously. Beneath the surface, the stakes have never been higher or the contest sharper, whatever diplomats and politicians may say publicly. Should these two giants find a way to coexist without betraying their core interests—through what I call managed strategic competition—the world will be better off. Should they fail, down the other path lies the possibility of a war that could rewrite the futures of both countries and the world in a way we can barely imagine.’

The problem with this notion is that neither Kevin Rudd nor Australia has enough influence to deliver it. Bejing and Washington will do what they do.

Sure, we can put our two bobs worth in. The iron ore trade is the real point of influence with China, so we can make it plain that it will be stopped during war.

And we can go to Washington. As the southern anchor of the US liberal empire in Asia, we have some influence.

But to bank everything on “managed competition” is as foolhardy as it is academic. Ultimately, Beijing will do what is best for the CCP vis-a-vis domestic politics. Ditto Washington.

Thus, the calculation of what is pragmatic is very different to what it used to be.

China has not liberalised as Australia hoped.

America is no longer willing to bear the costs of Chinas rise.

The corrallory is that increasing Chinese influence in Asia, or dominance of it – war over Taiwan or not – presents Australia with existential questions about the viability of its liberal democracy.

That is the only pragmatic consideration for anybody with the faintest notion of the Australian national interest.

The responses should be straightforward:

- diversity trade at pace and push out Chinese influence at home;

- build strategic capability that supports US power abroad.

Albo is doing the latter but not the former, which is a problem.