The conflict in the Middle East has caused oil prices to surge. This could lead to a cost-push inflation spiral: higher inflation –> higher wage demands –> higher inflation. Or, it could lead to demand destruction as higher fuel costs squeeze household budgets. For investors, working out which factor will dominate is important.

Post-pandemic, inflation primarily started when extra demand from supply chain restocking met problems with supply chains. Then, the Ukraine war hit. Sanctions on Russia saw energy prices boom. We are now in an extended period of wage rises, particularly in the US. As inflation fades away, is there potential for another spike in oil due to problems in the Middle East? We will look at this from three angles: geopolitical, demand, and supply.

1. Geopolitics

I won’t comment on the ethics of the Israel/Palestinian conflict. I will note it is an interminable conflict. And this time, there are dimensions we haven’t seen.

This is a proxy war

More so than in recent decades. Israel has always had strong US backing, but perhaps the Palestinians didn’t have quite so much regional support.

On one side, we have Israel and its various liberal state supporters, particularly the US. On the other side, Palestinians are backed in some measure by Iran, a client state to both Russia and China. These tendrils reach into the liberal-democratic versus autocratic Cold War 2.0 that has developed over the last few years.

What does this mean? It means that Iran gave the Hamas attack the green light. The goal: derail an Israel/US/Saudi Arabia deal. Saudi Arabia was going to officially recognize Israel and establish diplomatic ties in return for greater strategic links and a strategic guarantee. On the ground, the former PLO running the West Bank was to be promoted as the legitimate leadership of the Palestinians, directed at Iran as an encirclement by US allies.

Hamas scuttled this entire plan by attacking Southern Israel and enraging the Arab “man on the street”, making it impossible for Saudi Arabia to continue. The deal has more or less collapsed, and so Iran has effectively met its geopolitical objectives in allowing Hamas to proceed.

Iran’s goals have already been achieved

This is horrible news for those living in the region. But it does mean Iran has no reason to press the conflict further: it has already achieved its goals. This does assume a certain level of rationality on Iran’s part.

However, there is a possibility of more localized expansion, with Iran’s proxy Hezbollah in Lebanon a potential issue for escalation. So far, however, they have been restrained. You wouldn’t describe their rocket attacks into Northern Israel as more than virtue-signalling support.

Israel has no interest in expanding the conflict. China and Russia might like to see the US bogged down, but it’s hard to see that Israel would need US “boots on the ground”. Russia could benefit from a two-front war for the US, but it could also destabilize Syria and draw them in. China is more interested in getting the cheapest possible oil from whoever will provide it.

Is an oil embargo likely?

Could an oil embargo be a way for the various dictatorships and totalitarian states to vent their anger on the streets? Possibly, an Iran-led oil embargo could be implemented. But, it is uncertain whether Saudi Arabia would participate, given its various machinations to reform alliances across the Middle East.

The Saudis have oodles of spare capacity, which is why oil prices rose before the conflict. They have taken oil off the market, making it unlikely that an embargo would be agreed upon. Nonetheless, a risk premium has been built into the oil price.

Why hasn’t the oil price moved more?

The Russian and Iranian oil are both subject to sanctions, preventing them from being bought by European countries.

Before the war started, oil was already projected to go above $100 due to tight supply-demand dynamics in Q4. The war has merely short-circuited the consolidation period after the price jump.

It isn’t clear exactly why the price hasn’t moved more. Some is troubled global growth. The oil shortage argument may be weaker than thought.

2. Cost Push Inflation

Central banks ignore the direct effect, include the indirect impact.

The distinction must be made between headline and core inflation. Central banks focus on core inflation, which excludes food and oil.

Energy is not part of core inflation because it is so volatile. But oil is a major input for plastics, polyester, and many other goods. This is on top of the direct effect of higher transportation costs. Both lead to higher inflation.

As oil prices rise, central banks may feel more pressure to act. The Ukraine war put a rocket under inflation in the US. So, the US central bank will be more sensitive to a potential rerun. In Australia, the central bank might be more likely to look through the oil shock as there is less wage pressure.

Greedflation might be back…

When oil prices go up, transport companies often raise prices beyond the cost of oil. This could be seen as ‘greed inflation’, companies raising prices to expand margins. As a central banker, this would be concerning.

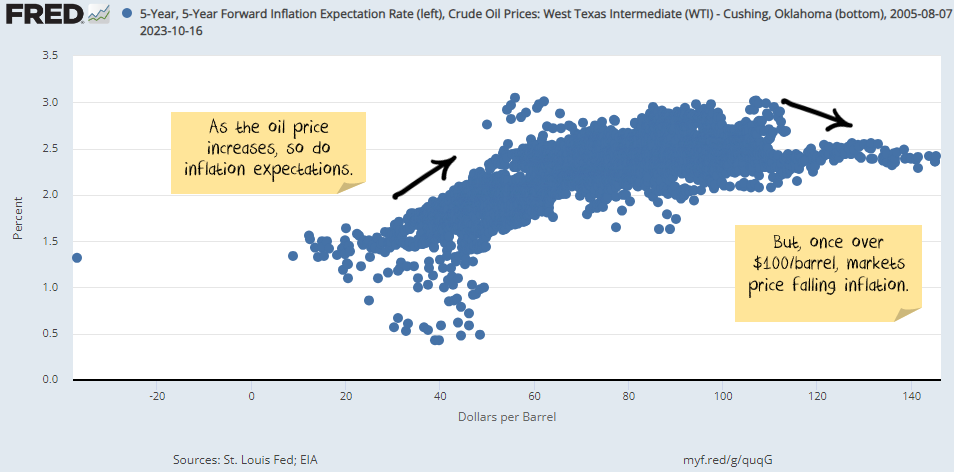

Markets tend to look at oil prices > $105 as destroying demand.

The five-year forward pricing can be used to deconstruct the market’s expectation for inflation over the next 10 years. Central banks often use this to gauge whether the market is pricing in problems. Once oil prices reach $105, it looks like markets start to factor in lower inflation. Implying the potential destruction of demand.

Are consumer savings running out?

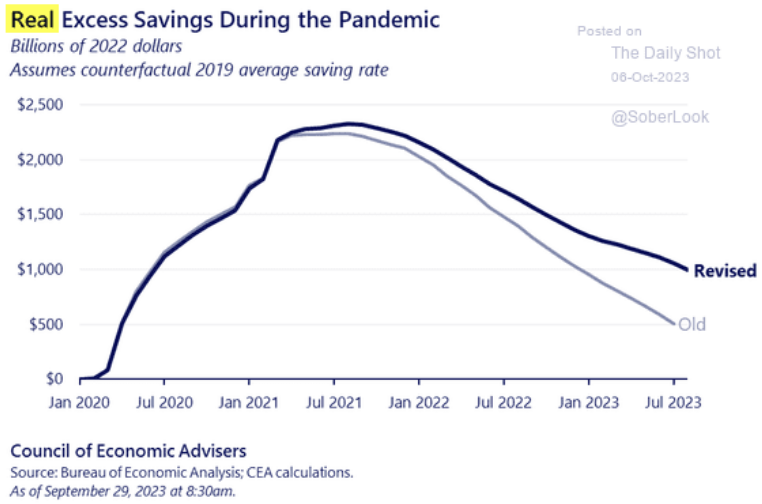

Increased consumer savings during the pandemic may have also contributed to stronger economic growth. Recent revisions show that US consumers built up an extra $2.5 trillion in excess savings since January 2020:

This has been slowly running down, resulting in stronger growth.

But, if you stratify the numbers by income, poorer people have already exhausted their savings.

What about electric vehicles?

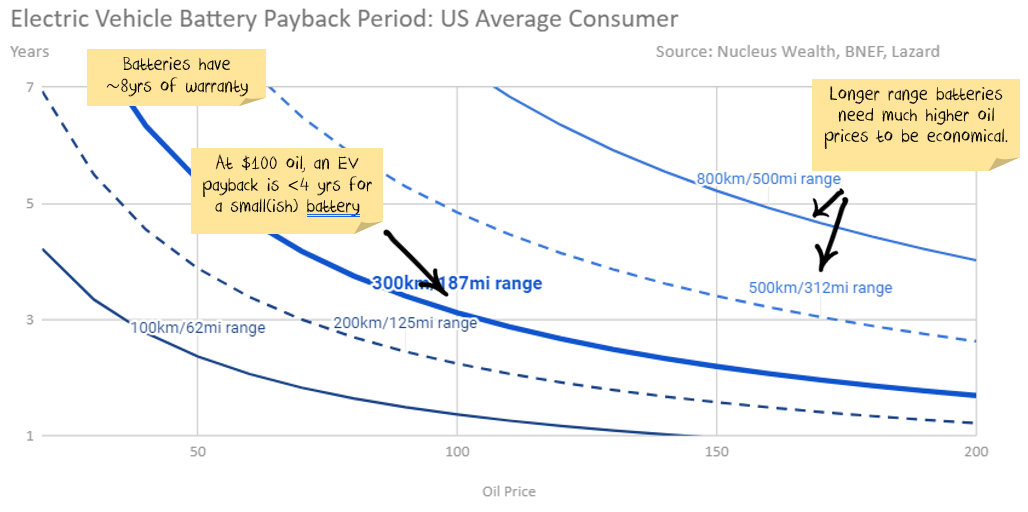

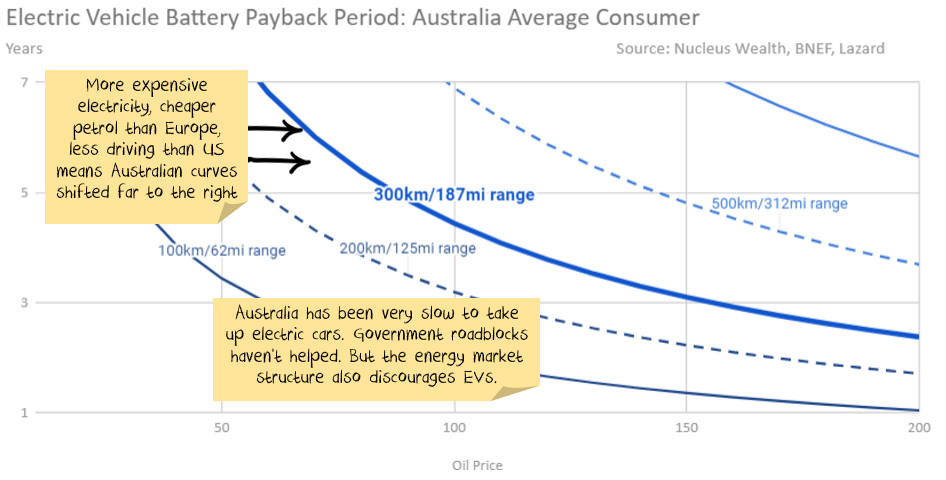

The higher the oil prices rise, the more economical it becomes to switch to electric vehicles. This reduces oil demand permanently. Electric vehicle costs are falling. But battery costs are not low enough (yet!) to justify switching on an economic basis for an average consumer in most countries.

Every $10 oil price change adds or subtracts 0.5 years to the payback at current oil prices. But it is not linear. And it varies by country.

It is mostly about range anxiety.

Payback is my preferred way to look at electric vehicles:

- How much extra for the battery

- How much do you save each year

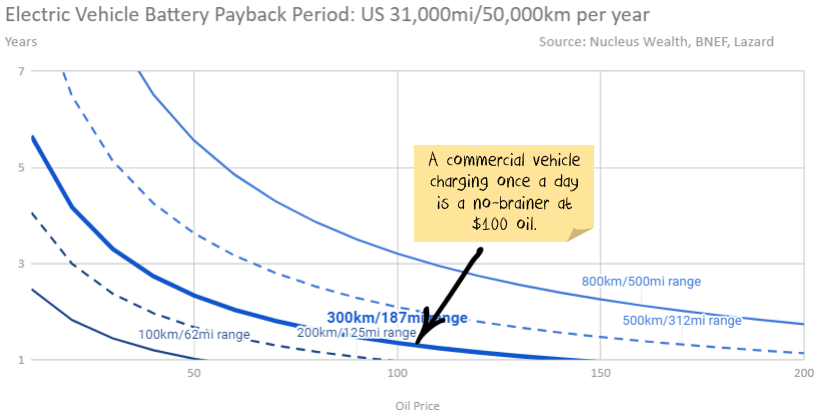

For commercial vehicles, payback is already good enough. In the US, travelling 150-200km daily, the payback is less than two years if you are happy with a 300km range battery. If you can charge throughout the day and use a 150km range battery, you can halve the payback period:

However, consumers have more random travel demands. And so more range anxiety. But drive less. With an 800km/500mi battery range, the average US consumer would need the oil price to be more than $200 to make the payback period reasonable:

In Europe, fuel and electricity are more expensive, but the distance travelled is much lower. In Australia, payback is much worse. Australians drive less than the US, and electricity costs are higher.

Net effect – oil prices aren’t high enough

Higher oil prices will lead to more consumers switching to electric. But the economics aren’t particularly attractive. And probably won’t be until 2030.

Battery costs have halved over the last six years. They will need to do that again. A price war in Chinese production is helping. Solid-state batteries will help, but they are also five years away from mass production.

Driverless vehicles? As commercial vehicles, they already make economic sense to be electric. The rollout is happening, but even the most optimistic assumptions have mass adoption five years away.

3. Investment impact

Initially, yields fell sharply on a safe haven trade into bonds when Hamas attacked. Bonds are an interesting question now. If we see:

- Oil embargo, oil price spikes: the market will start factoring in a negative shock to growth. Bonds look attractive, and equities fall. This is a lower probability outcome.

- Limited escalation, oil price remains steady: then inflation expectations will increase. Negative for growth. Bonds and equities both likely fall.

- Gradual de-escalation, oil price fades: inflation expectations also fade. Bonds look attractive; equities will depend on how quickly broader demand is falling. There are both positive and negative possibilities for equities.

Bigger picture, developed markets are significantly more financialized than in the past. Meaning that if stocks fall enough, they would also deliver a blow to consumers. Even if not, equities based on both price and earnings will need to be discounted.

Markets are now back to average valuations. The bigger question is company earnings. But more on that another time.

Damien Klassen is Chief Investment Officer at the Macrobusiness Fund, which is powered by Nucleus Wealth.

Follow @DamienKlassen on Twitter or Linked In

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Limited, Australian Financial Services Licensee 515796. And Nucleus Wealth is a Corporate Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Ltd.