The baby boomer generation has won the intergenerational lottery.

Successive Australian governments have stacked policy in favour of older residents at the expense of the young.

We have provided older Australians with substantial tax benefits. Older Aussies can earn significant incomes that are mostly tax-free, whereas younger Aussies earning the same amount are required to pay up.

The baby boomer generation fortuitously entered the housing market when homes were still reasonably priced, giving them the highest home ownership rate in the nation.

They then capitalised on rampant price inflation, which priced-out their children and grandchildren.

A significant number of baby boomers also acquired one or two investment properties.

Most decent jobs did not require a university degree 40 to 50 years ago. But most boomers who did attend university received free education.

By contrast, tuition costs for younger Australians have become a substantial financial barrier early in life.

Intergenerational inequality has worsened since the pandemic:

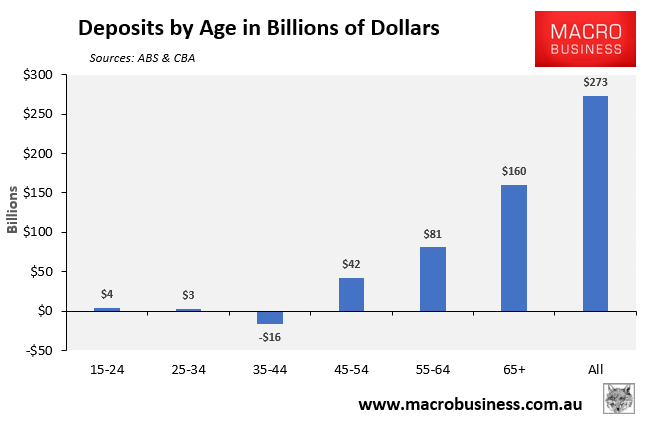

Australia’s national accounts from the ABS showed that households saved an astonishing $273 billion over the COVID-19 pandemic, courtesy of the various government stimulus packages and reduced consumer spending during lockdowns.

However, as shown below, the overwhelming majority of these savings ($160 billion) went to Australians aged 65 and above, followed by Australians aged 55 to 64 ($81 billion):

By contrast, younger Australians aged 45 and under saw their savings decline, with those aged in the key home buying and child-rearing demographic of 35 to 44 hit hardest.

Roy Morgan’s Wealth Report 2023 showed that Australia’s wealth increased by 7.0% from March 2020 (pre-COVID) to March 2023.

The majority of this increase in wealth was attributable to a 43.2% increase in the value of owner-occupied properties, from $4.16 trillion to $5.95 trillion.

The overwhelming majority (95.4%) of Australia’s net worth is currently held by half of the population, who are primarily homeowners.

By contrast, the net wealth of the lower half of the population, predominantly renters, was a mere 4.6%.

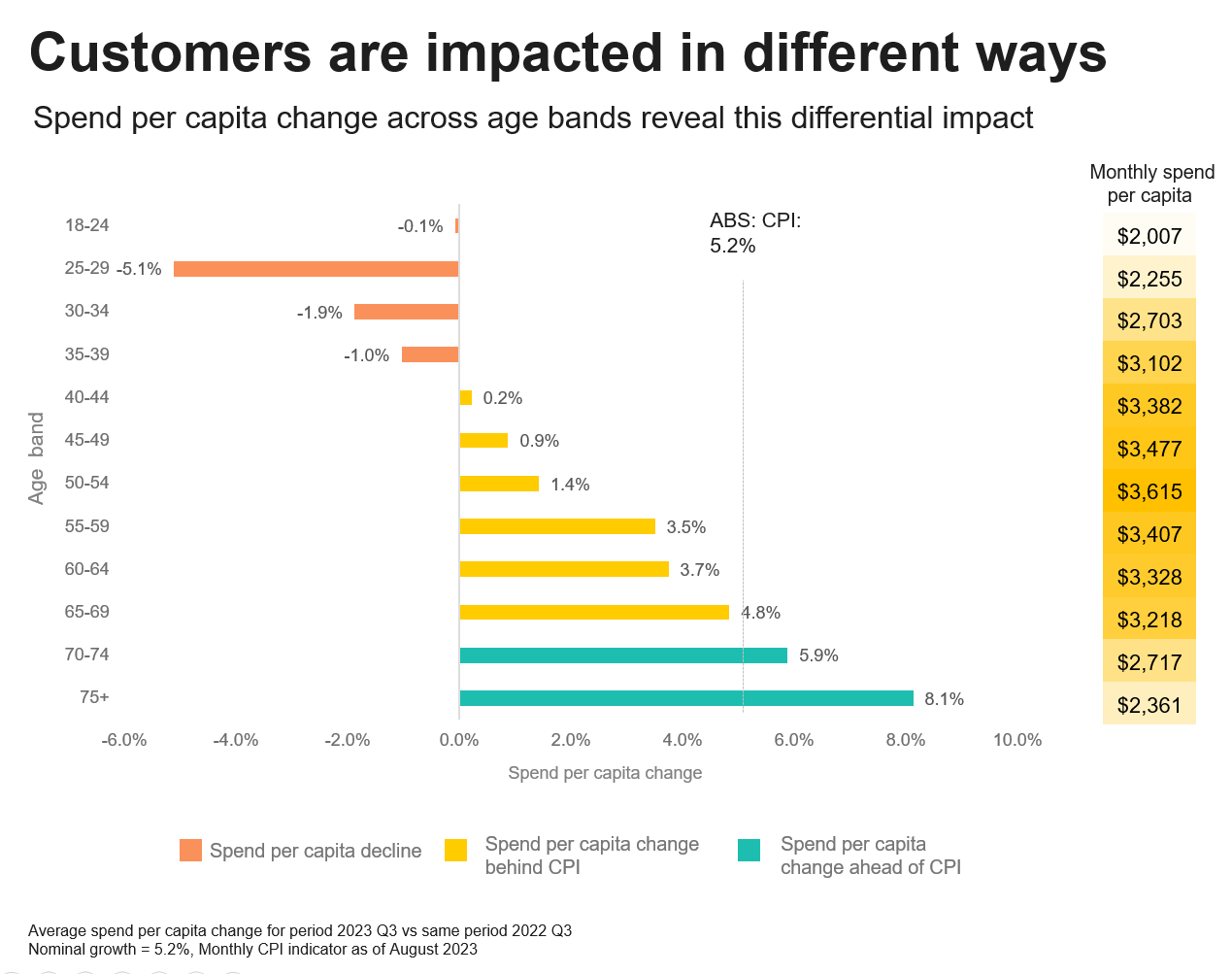

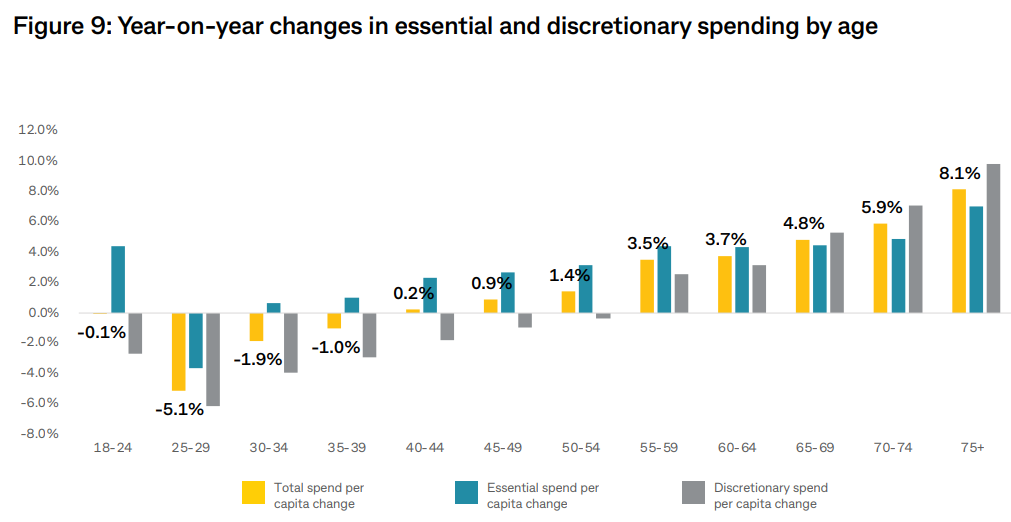

This week, CBA released data on spending habits by age cohort, which showed a huge increase in spending by older Australians, while spending by younger Australians has shrunk:

Younger Australians are cutting back especially hard on discretionary spending, whereas older Australians are spending like drunken sailors:

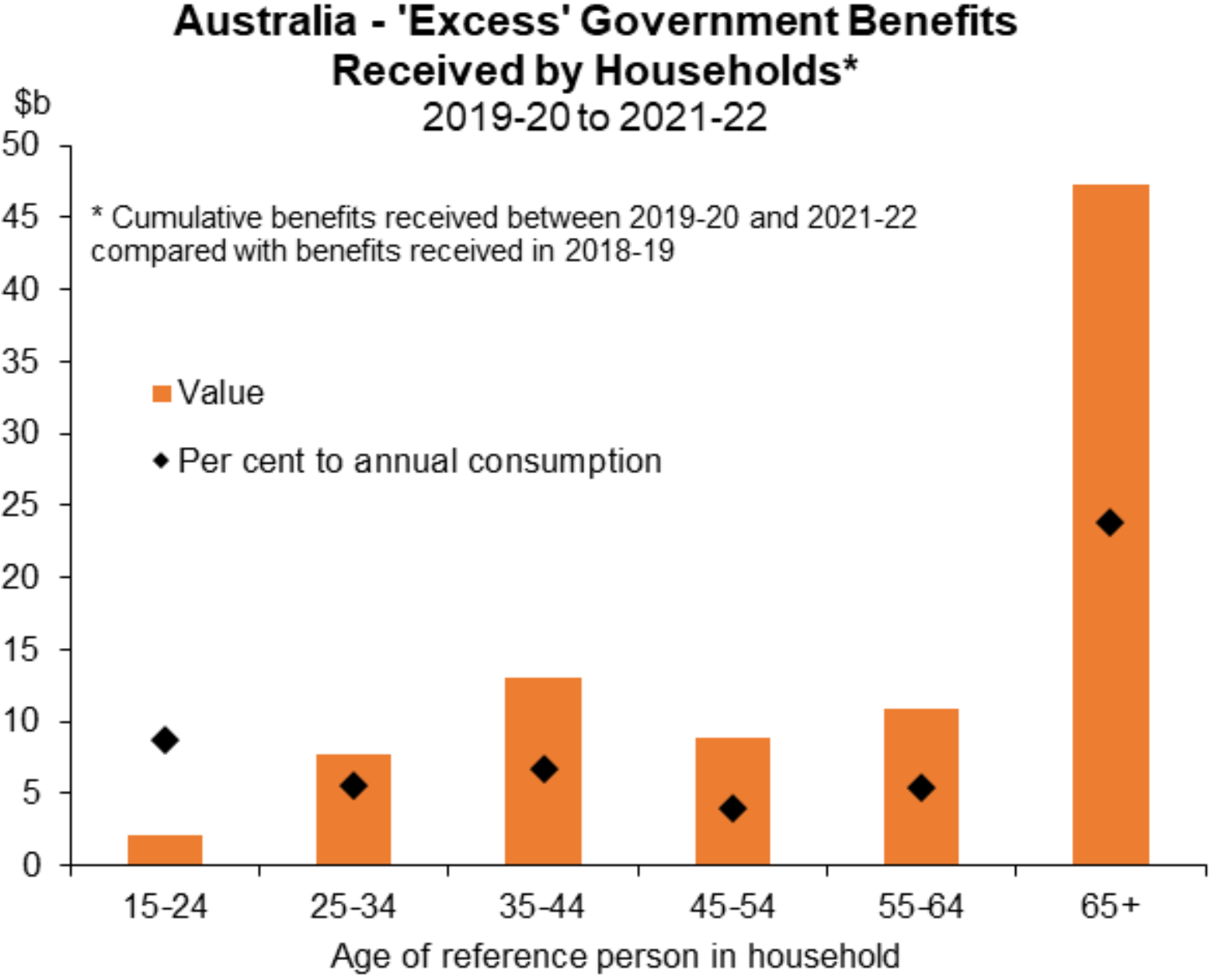

The inequity between generations is also present with respect to government subsidies and handouts.

Macquarie Goup’s Justin Fabo conducted an analysis of all subsidies provided by governments to different age cohorts using data from the ABS national accounts:

Source: Justin fabo (Macquarie Group)

As shown above, the majority of ‘excess’ subsidies went to Australians aged 65 and over.

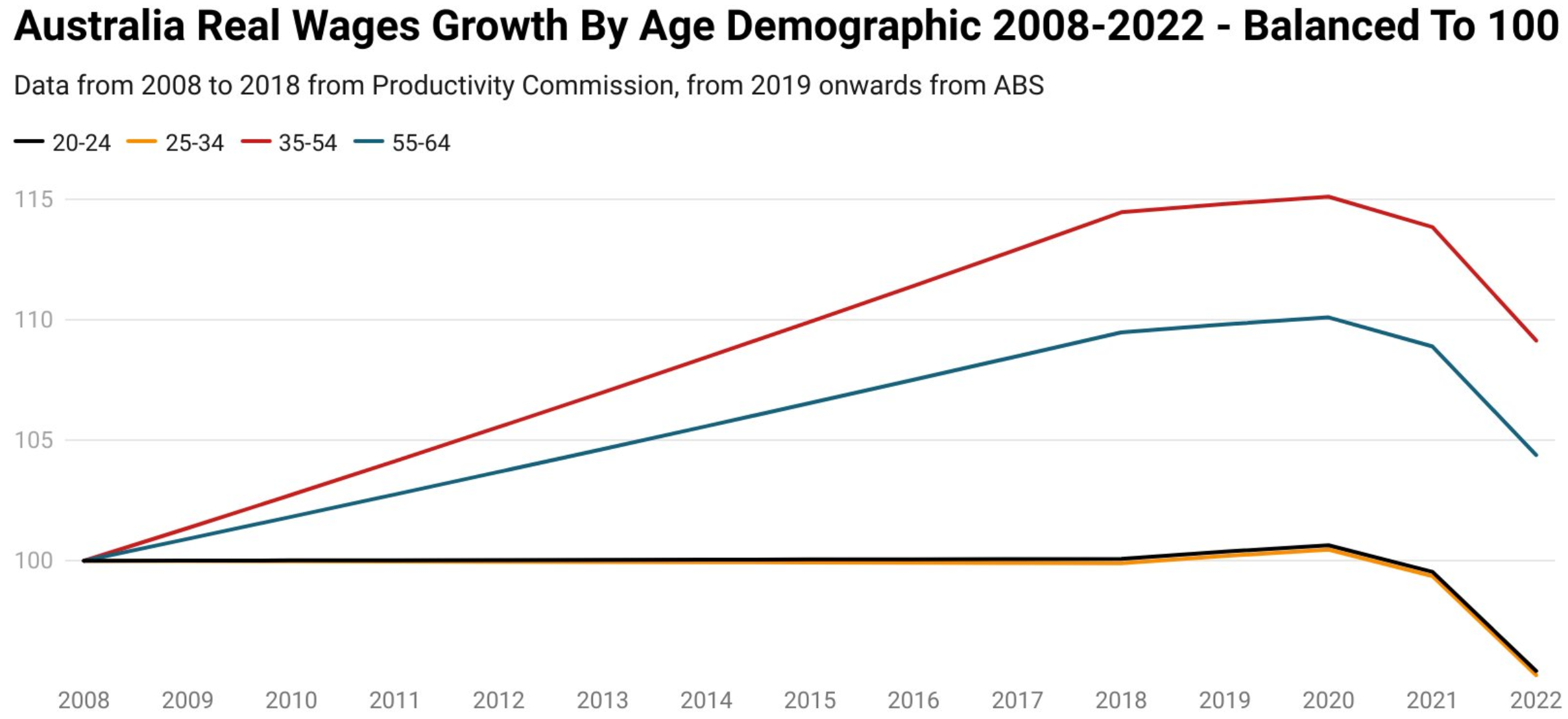

Finally, the real wages of younger Australians have fallen over the past 15 years, unlike older Australians:

Source: Tarric Brooker

There are three Australia’s right now.

Rapid interest rate increases by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) have a direct impact on roughly one-third of mortgage-holding households, particularly Generation X and Millennials with young children.

Their mortgage payments have increased by more than 50% while their disposable income has been eroded at the fastest rate on record due to inflation and rising cost-of-living.

Another one-third of renting households (mostly young) are being hit hard by rapid rental inflation, in addition to plummeting real wages, which is reducing their discretionary spending.

The remaining circa one-third of Australians are dominated by baby boomers and are travelling nicely.

Most baby boomers own their homes outright and are unaffected by the rapid rise in mortgage rates and rents.

Baby boomers also hold a large share of the nation’s investment homes (many without a mortgage), so are profiting from soaring rents.

Unlike worker’s incomes, Australians on the aged pension have their payments tied to inflation, ensuring that their spending power remains stable as prices rise.

The final insult comes from the fact that the profligate spending of older Australians is working against the RBA’s efforts to slow the economy and is being met with higher interest rates, which is punishing younger Australians with mortgages.

To the baby boomers go the spoils.