By Gareth Aird and Stephen Wu from CBA Economics

Key Points:

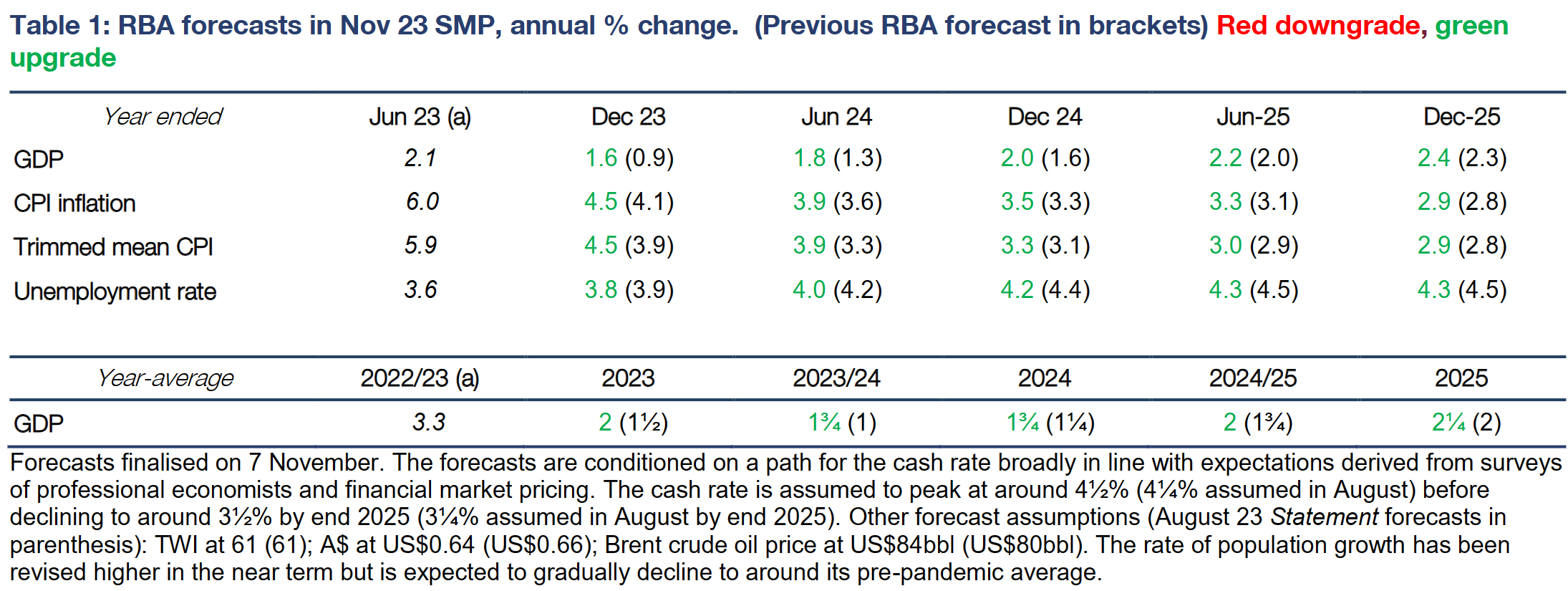

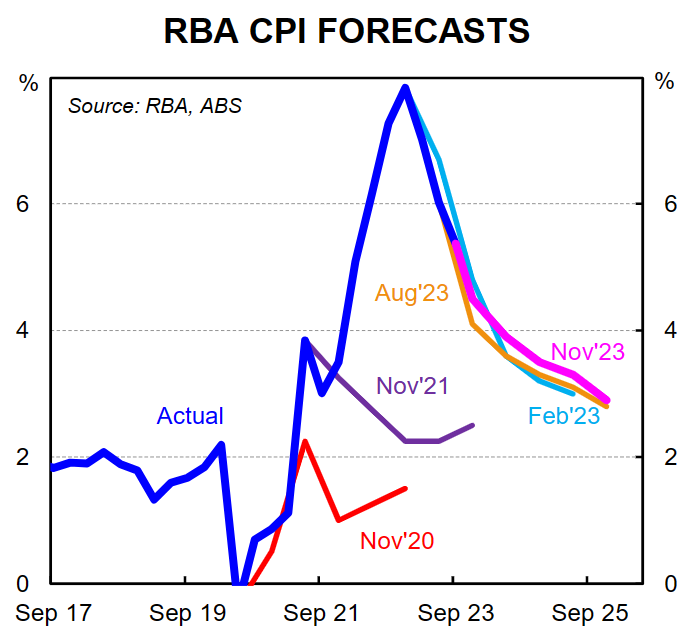

- The RBA has upwardly revised their inflation forecasts, but retained the view that inflation will return to the target band by end-25.

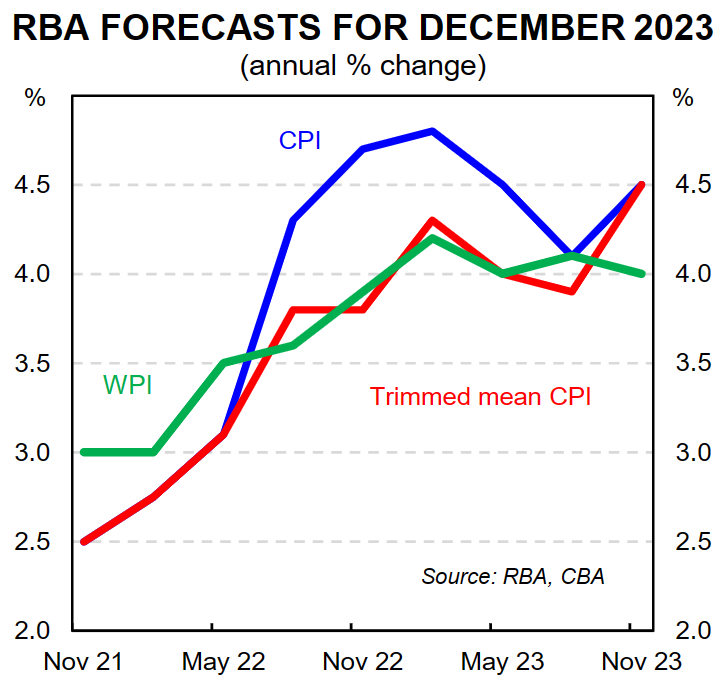

- The RBA expects annual inflation to be 4.5% in Q4 23 and 3.5% in Q4 24.

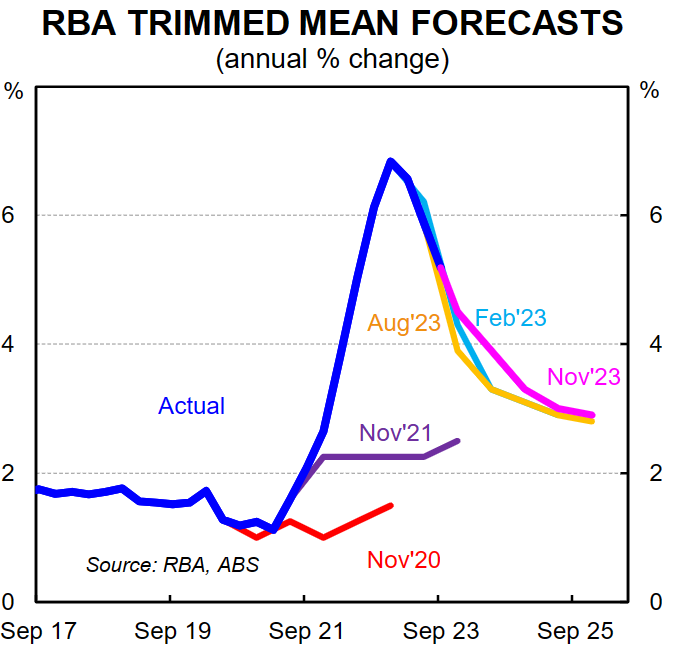

- The annual rate of underlying inflation is forecast to be 4.5% in Q4 23 and 3.3% in Q4 24.

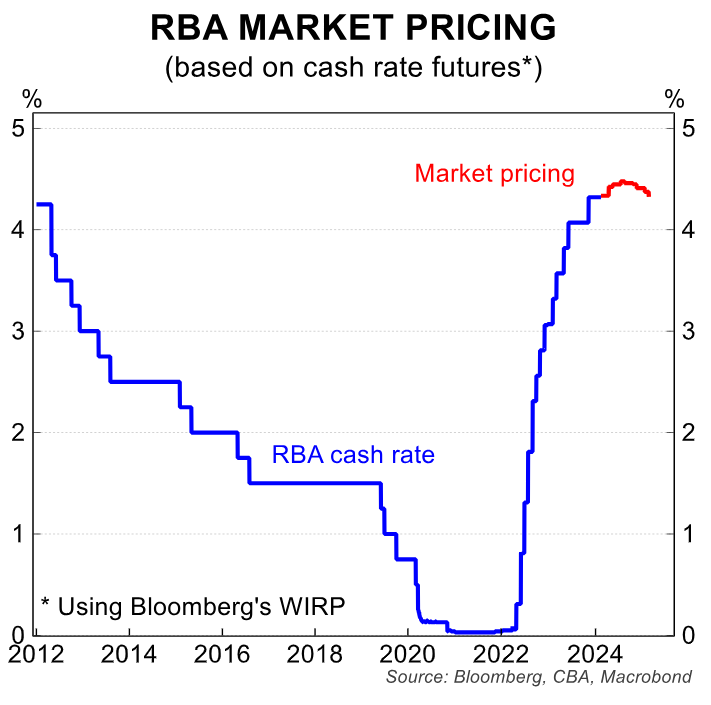

- The RBA’s forecasts assume a peak in the cash rate of around 4½% before gradually declining to 3½% by end-2025 (the cash rate target is currently 4.35%).

- The RBA has upwardly revised their 2023 GDP forecast to 1.6%/yr in Q4 23 (from 0.9%/yr previously). Stronger than expected investment and services exports have been partially offset by a weaker outlook for the consumer.

- The RBA has lowered their profile for the unemployment rate. The RBA expects the unemployment rate to be 3.8% in Q4 23 (from 3.9% previously) and 4.2% in Q4 24 (from 4.4% previously).

- The RBA has made a slight downward revision to their profile for wages growth across the forecast horizon. Upward revisions to inflation forecasts and minor downward revisions to wages growth imply weaker real wages growth.

- Our base case sees the RBA hold the cash rate at 4.35% until Q3 24, when we look for an easing cycle to commence.

RBA’s updated forecasts suggest the next ‘live’ meeting is February 2024:

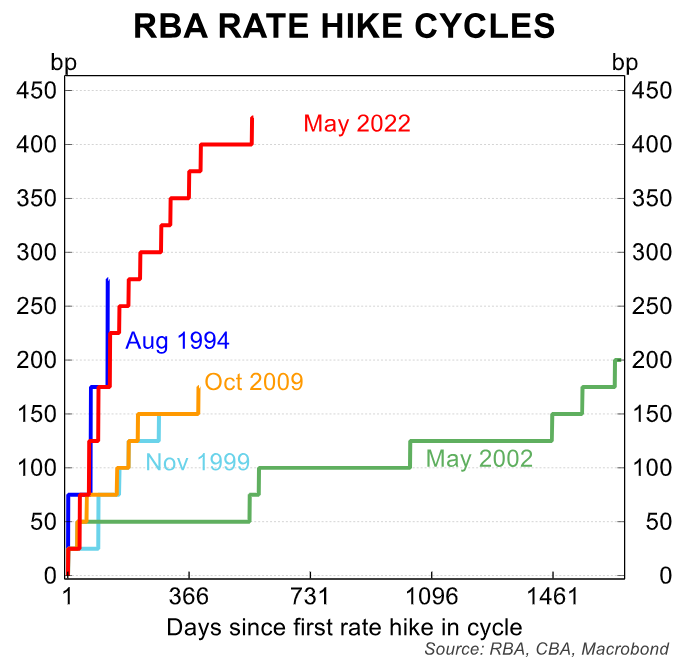

The RBA’s November Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) comes in the wake of the 25bp rate hike at the November Board meeting, which took the cash rate to 4.35%.

The increase in the cash rate was the first change in policy for five months (recall the RBA increased the cash rate by 25bp to 4.10% in June).

Both money markets and the forecasting community expected a rate increase on Cup Day given the upside surprise in the Q3 23 CPI (particularly the strength of the trimmed mean CPI).

The Governor’s Statement accompanying the November Board decision noted that, “the Board judged an increase in interest rates was warranted today to be more assured that inflation would return to target in a reasonable timeframe”.

The increase in the cash rate in November allowed the RBA to retain their forecast for inflation to be at the top of the target range of 2-3% by the end of 2025.

Indeed, the Governor noted that in her statement on Tuesday. But there was a lack of detail on the RBA’s assessment on the near-term trajectory for inflation.

The November SMP provides this detail as it tables the key semi-annual point forecasts to the RBA’s inflation profile to end-2025.

The November SMP also provides updated point forecasts for GDP, wages growth and the unemployment rate.

The near term point forecasts are very important given the RBA has a tightening bias. The point forecasts provide markers in which we can assess if the economic data is printing stronger, weaker, or in line with the RBA’s expectations.

By extension there are implications for the near term monetary policy outlook depending on how the data evolves.

The current forward guidance states, “whether further tightening of monetary policy is required to ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe will depend upon the data and the evolving assessment of risks.”

This is a slightly watered down version of the forward guidance from the October Statement. But the overall message is little changed.

The Board would prefer not to raise rates again in this cycle. But they are very much data dependent.

This means the Board is willing to raise the cash rate again if the economic data, particularly around inflation, comes in stronger than their updated forecasts.

The near term forecasts are very important for markets:

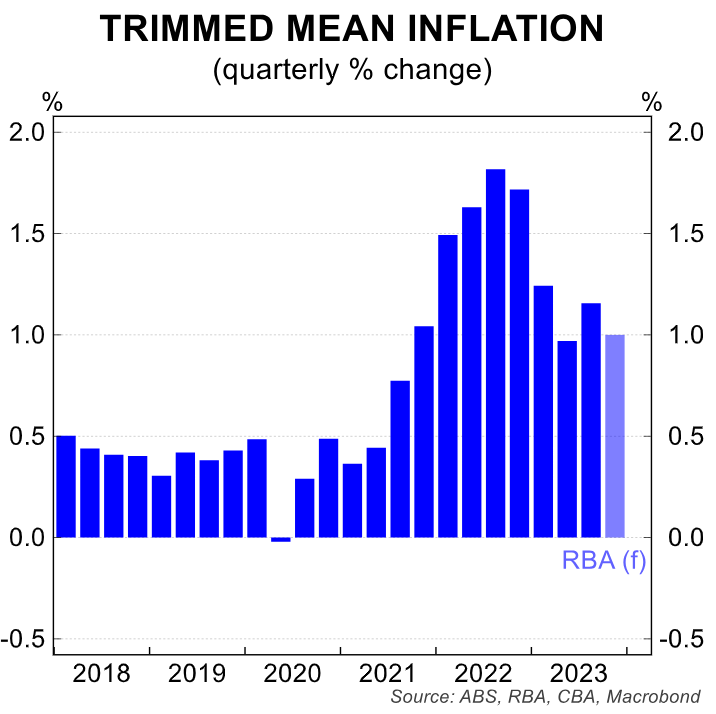

The RBA’s forecast for headline CPI to be 4.5%/yr in Q4 23 means that the RBA expects a 1.0%/qtr outcome in the December quarter.

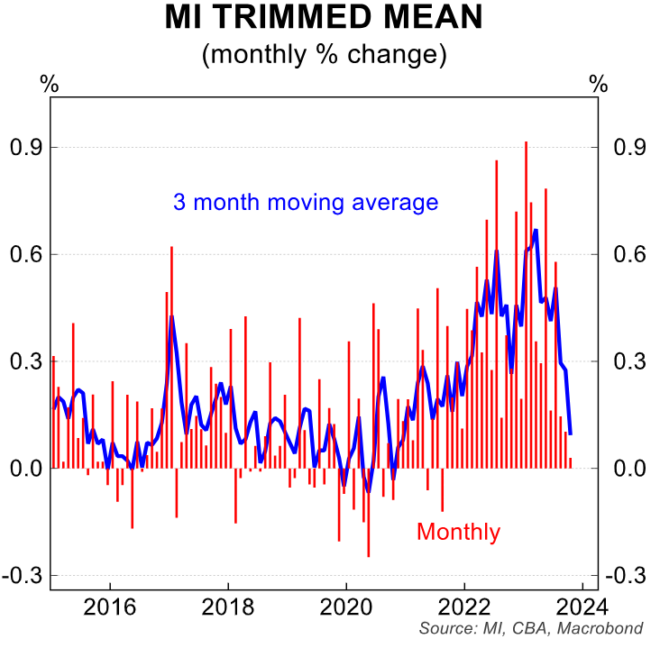

For trimmed mean inflation,the more important measure for monetary policy, the RBA has forecast 4.5%/yr in Q423. This means they expect a 1.0%/qtr outcome.

A quarterly outcome on the trimmed mean of 1.0%/qtr in Q4 23 would represent a slight easing on the 1.2%/qtr increase in Q3 23.

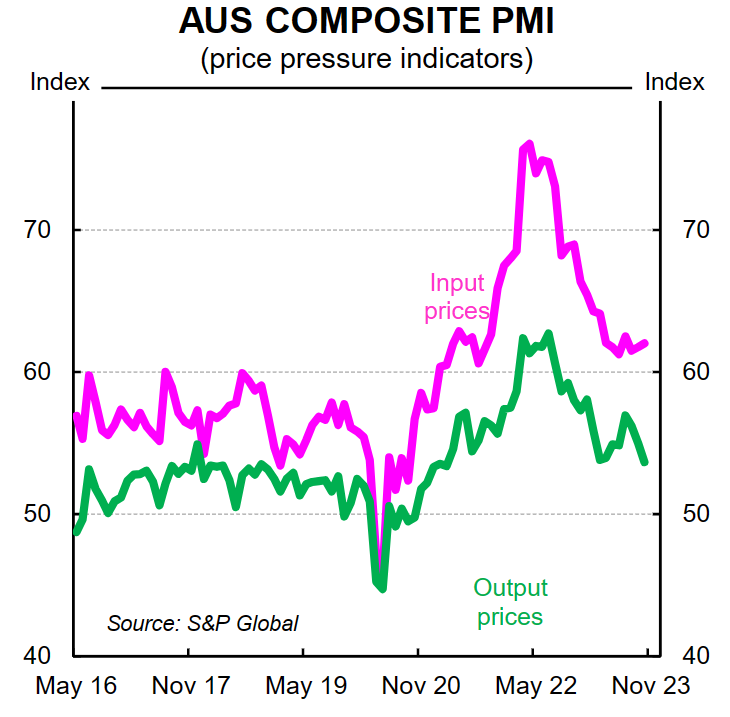

But it looks a reasonable forecast based on some already released prices data for October (Melbourne Institute’s monthly inflation gauge and output prices from the PMIs were both encouraging prints–see below charts).

The RBA has forecast wages growth, as measured by the WPI, to be 4.0% in Q4 23 (downwardly revised from previous 4.1%/yr). We estimate they expect a~1.3%/qtr increase in Q3 23 and a ~0.9% lift in Q4 23.

The Q3 23 WPI is published next week (15/11). Our internal data points to a 1.2%/qtr increase, which is a touch below the RBA’s expectation.

On that basis, we think it unlikely that we will see a material upside surprise relative to the RBA’s forecast (a material upside surprise relative to the RBA’s forecast is 1.5%/qtr or above –this looks quite unlikely).

The SMP noted that the large lift in the minimum and award wage had not resulted in larger than usual spillovers on the wages of other workers.

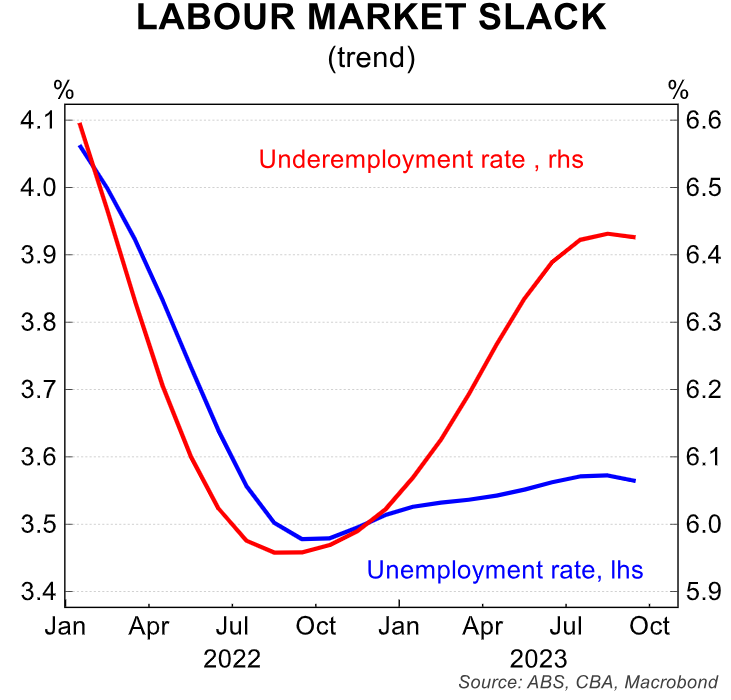

On the unemployment rate the RBA has forecast it to average 3.8% over Q423. The unemployment rate dipped by 0.1ppt in September 2023to 3.6%.

So, the RBA is expecting a gradual upward trend in the unemployment rate to establish itself from here. We agree with that assessment.

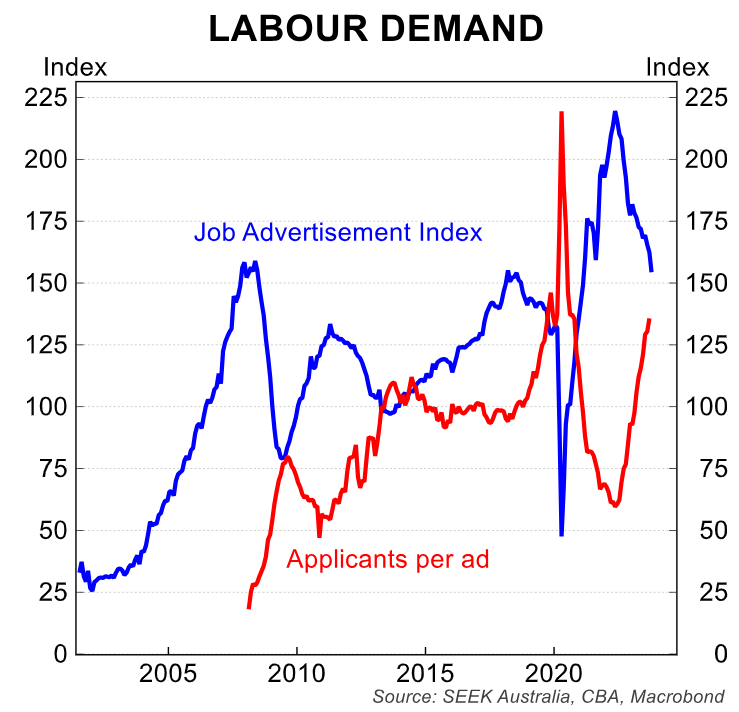

Here we note that other measures of the labour market have loosened more meaningfully. Job advertisements are in a firm downward trend. And the underemployment rate has risen by more than the lift in the unemployment rate.

There are now more workers that are seeking additional hours to cover higher rent or higher mortgage repayments as well as the general increase in the cost of living.

The RBA forecasts GDP growth of 1.6%/yr in Q4 23. This implies a lift in GDP over ~0.4%/qtr in both Q3 23 and Q4 24.

This is below population growth, which implies the per capita recession continues over 2023.

The RBA’s near-term GDP profile is very similar to ours – we forecast GDP growth of 0.4%/qtr in Q3 23 and 0.3%/qtr in Q4 23.

The bigger picture:

The RBA’s forecasts for the economy and inflation over 2024 and 2025 are less relevant for the near term policy outlook (see Table 1 below for the key numbers).

In many respects the RBA want their medium-term forecasts to come to fruition. As such, their policy settings at this juncture are designed to try and achieve these outcomes.

But the RBA will only know if their medium-term forecasts are on track based on how the near-term data prints relative to their expectations.

The RBA’s forecasts over 2024 and 2025 are consistent with the ‘narrow path’ narrative.

The economy is forecast to grow below trend. By extension, the unemployment rate gradually rises. Wages growth stays consistent with the inflation target and inflation falls back to within target over the forecast period.

Most economists have a similar base case to the RBA (us included). It is the obvious central scenario when monetary policy sits in restrictive territory.

The conjecture across the forecasting community is around how fast the economy will slow, how quickly inflation will return to target and the speed and magnitude of the expected lift in the unemployment rate (we expect the jobless rate to rise a little more swiftly than the RBA over 2024).

The key for markets is the path of monetary policy. Here we note that the RBA’s forecasts assume a peak in the cash rate of around 4½% before gradually declining to 3½% by end-2025 (the cash rate target is currently 4.35%).

Our economic forecasts inform our call on the cash rate over the medium term. Our base case sees the RBA on hold until September 2024, when we have pencilled in the start an easing cycle.

We have 75bp of rate cuts in late 2024 and a further 75pb of easing in H125, which would take the cash rate to 2.85% (this assumes no further increases in the cash rate).

Monetary policy works with a lag in both directions. And we think that with inflation receding a little more quickly than the RBA expects and unemployment rising more quickly the Board will want to take the cash rate down from Q3 24 to keep the economy ‘on an even keel’.

We also don’t know the Board’s reaction function to ease policy. Our working assumption is that the annual rate of inflation does not need to return to target before the RBA cuts the cash rate.

Rather, we think a six-month annualised pace of inflation that is close to target would be sufficient for the Board to ease policy, given inflation is a lagging indicator.

RBA’s assessment of balance of risks

Three months ago, the RBA viewed the outlook for inflation as little changed from its assessment in May. That is, that inflation was moving in the right direction and the recent flow of data was consistent with inflation returning to target in a reasonable timeframe.

The RBA had judged the balance of risks to their inflation forecasts as balanced. While there were upside risks to the inflation outlook, it was also possible that inflation could come down more quickly than in their central scenario.

In its most recent assessment, the RBA retains the view that there are both upside and downside risks to the inflation outlook. But, on balance, the upside risks to inflation have increased.

The RBA has partially accounted for an increase in upside risks to the inflation outlook by upwardly revising their near-term inflation forecasts.

The conflict in the Middle East and changing weather patterns add to the possibility of inflation staying high for longer.

Despite the upward revisions to the inflation profile, the RBA has downgraded their forecasts for wages growth. Timely indicators, from private sector surveys as well as from the RBA’s business liaison program, suggest that the annual pace of wages growth only picked up a little in the September quarter.

The 5.75% increase in the minimum and award wage and increases in public sector wage policies is being offset by moderating wages growth in other jobs and for non-award workers as the labour market loosens.

Our CBA wages tracker also indicates that wages growth will not be as strong as the RBA had previously expected.

The RBA appears more sanguine about the risks of a wage-price spiral emerging.

Evidence is growing that wages growth expectations are drifting lower as labour demand and supply imbalances have improved.

Overall, the RBA does still see the risks to the domestic outlook as ‘broadly balanced’. They caveat that this rests on the assumption that inflation expectations remain well anchored.

More generally, the RBA judges that the risks for the global economy are tilted to the downside. There is the potential for a further tightening in financial conditions to occur, particularly if inflation proves more persistent than currently anticipated.

Downside risks are also notable in China where weak economic growth, the potential for property sector stress to spill over to other parts of the Chinese economy, and uncertainty around policymakers’ response are adding to heightened uncertainty.

Risks to our call:

There are a lot of moving parts to the economic landscape at present, which adds to uncertainty around the economic outlook and the path of monetary policy.

In the near-term the balance of risks sits with a higher terminal cash rate than 4.35%. Another upside surprise in the Q4 23 CPI could see the RBA pull the rate hike trigger again.

Looking further out, the risks become more evenly balanced.

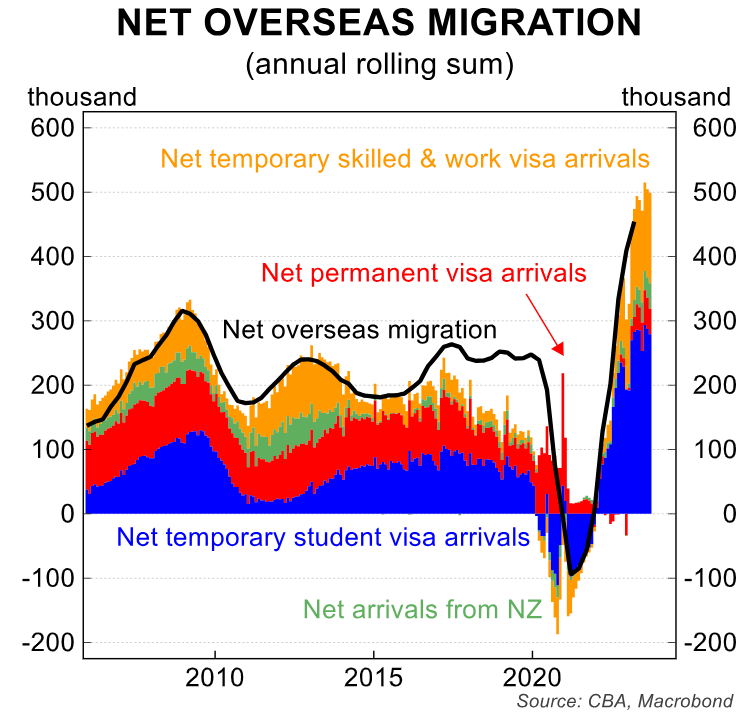

If population growth remains elevated or consumption strengthens due to rising home prices, it could make the RBA’s job of returning inflation to target more difficult.

In such a scenario, the cash rate may sit at its peak in the cycle for longer than we currently anticipate.

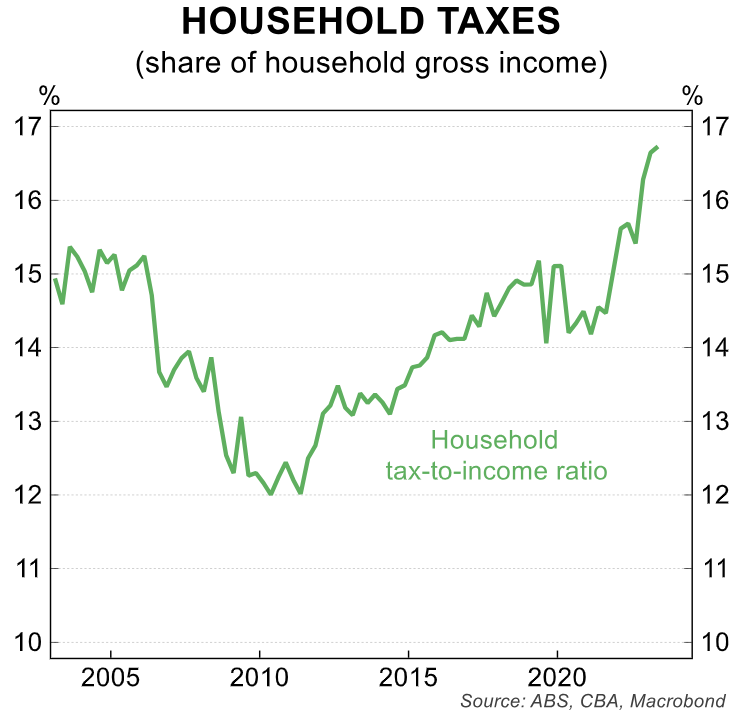

Fiscal policy is also a key source of uncertainty. Any loosening in fiscal policy at either the state or federal level would put upward pressure on demand and by extension inflation (note that the already legislated 2024 income tax cuts will provide some stimulus to the economy over 2024/25. But the tax cuts are simply reducing bracket creep given the personal tax-to-income ratio has surged over the past decade –see below chart).

Geopolitical uncertainty is also an upside risk to the inflation and rates outlook.

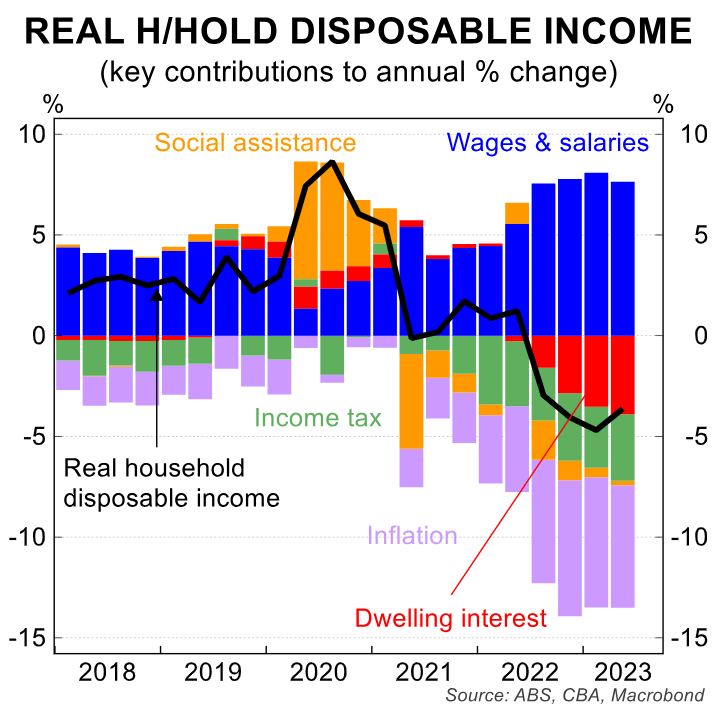

Working the other way is the risk that the lagged impact of interest rate increases weighs more heavily on the consumer in 2024.

There is still a lot of organic tightening to come via the ongoing expiry of ultra-low fixed rate loans. And the 25bp Cup day rate hike won’t flow through to higher mortgage repayments for variable-rate borrowers until February next year.

It may be the case that consumer behaviour through next year more closely marries up with how the household sector is feeling.

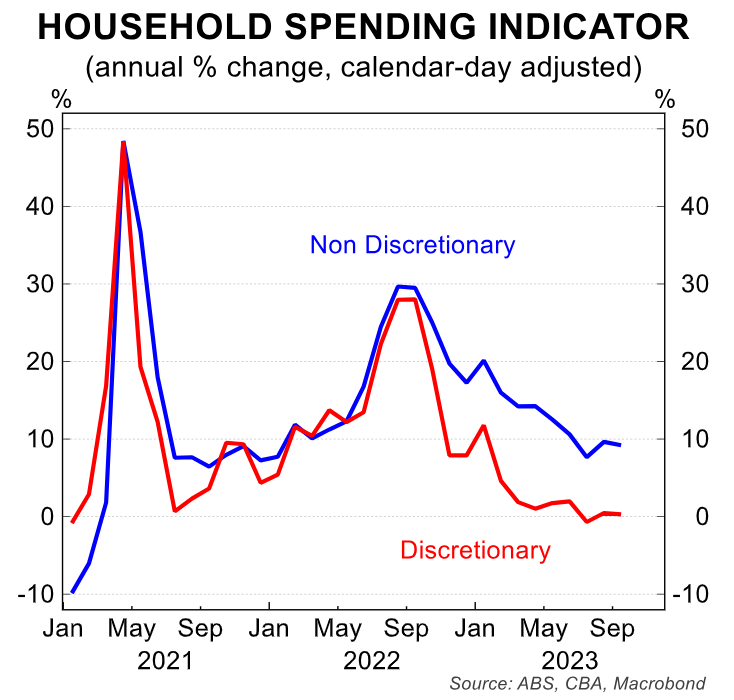

To date, the usual relationship between consumer sentiment and behaviour has not been aligned (see below chart).

But there is a risk the typical relationship reasserts itself next year and spending slows more quickly.

The CommBank Household Spending Insights (HSI) index will be an important source of information on consumer spending activity (the October CommBank HSI will be released on Monday 10/11).