By Stephen Saunders

Kohler’s Quarterly Essay highlights rank political failure to reduce housing unaffordability. His solutions underestimate Treasury’s reckless population and environmental overshoots.

Kohler, a financial journalist and ABC TV personality, gets much right in his Black Inc Quarterly Essay, The Great Divide: Australia’s housing mess and how to fix it. Yet he misreads the post-COVID mess. His fixes are ineffectual.

He discerns “dysfunctional” attitudes to land speculation in the original 1788 land rush, the gold rush after 1851. Melbourne real estate took “sixty years” to regain peak 1889 prices.

In his Figure 3, Australia’s “real” house-price index motored quietly over 1860-1950. But doubled after 2000.

Kohler bought his first Melbourne home in 1980 for $40,000, a couple multiples of earnings. Me too. I paid $40,000 in Melbourne in 1978. Dumb luck.

Houses now are “speculative investment assets”. House-prices are “almost everything”.

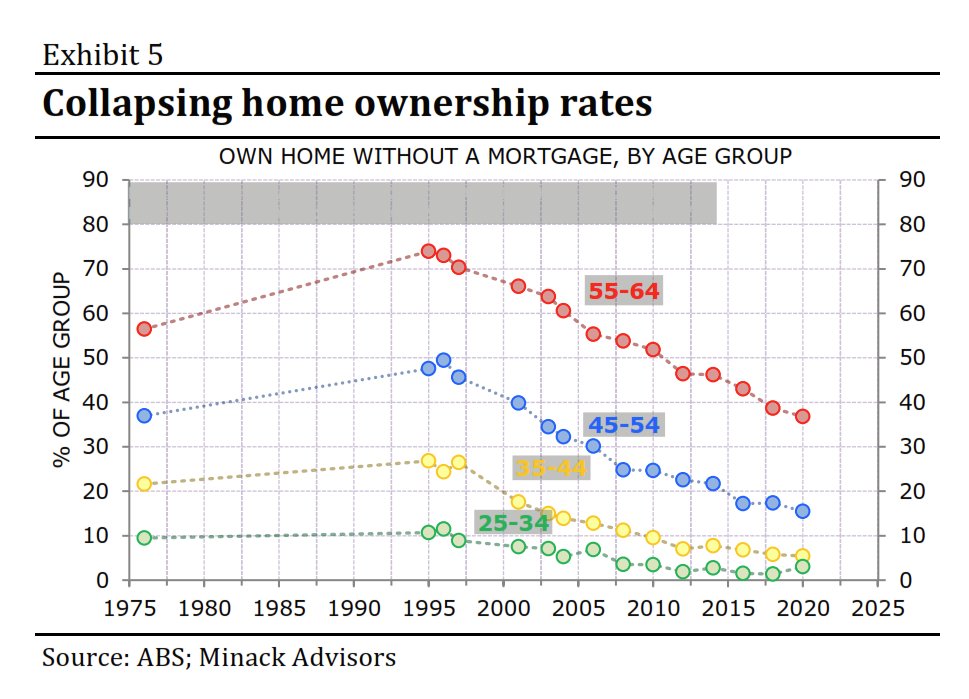

In Kohler’s number-crunching, it’s nigh impossible for an “average millennial family…to buy a home for the national median price”. As recently as 2000 this was “doable”.

Stepping in as a big home-lender is “Bank of Mum and Dad”.

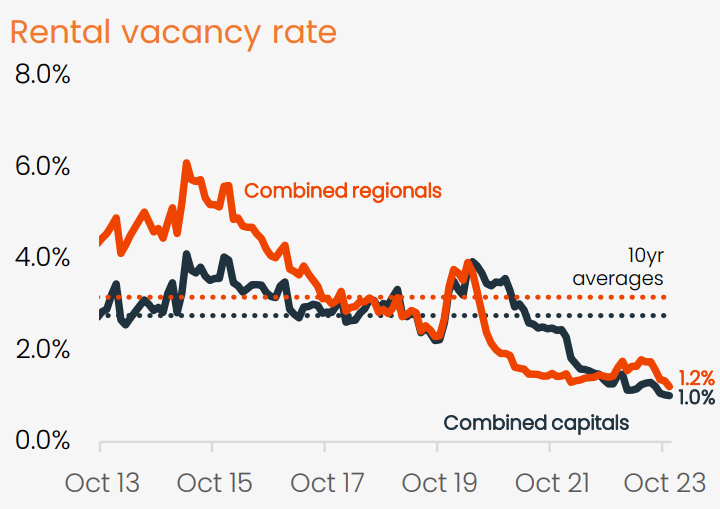

BMD entrenches “housing inequality”. Ouch, for poorer Australians. Over the last decade, rental vacancy rates have hit historic lows.

Source: CoreLogic

Our world-level housing unaffordability is a “stunning failure” made by worse by leaders, says Kohler.

Supply side analysis

Three chapters cover supply-side housing problems.

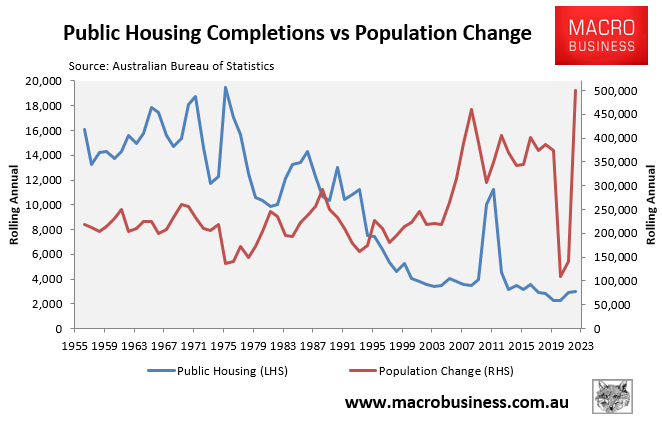

First comes “Public Housing”. Would you believe, PM John Curtin price-controlled “house and land purchases” in 1942. But war, I note, had virtually halted immigration.

The 1945 Commonwealth State Agreement began our “first and only serious” national housing policy. But 1945, I note, also introduced populate or perish.

By 1949, Bob Menzies wanted “little capitalists” to own their homes. Post war through to 1966, came our “largest ever” increase in home ownership.

By 1978, under Malcolm Fraser, public housing was more like “welfare for the neediest”.

Fast forward to 2022 and Albanese’s “Housing Accord”. For Kohler, it’s not fit for purpose.

His next problem is “Australia’s Crowded Sprawl”. Code for failed “decentralisation”.

Kohler blames this failure on the post-1945 success of commuter cars, against failure of regional (and commuter) rail.

But wait. Ever since 1945, Sydney and Melbourne have swallowed roughly 40% of Australia’s growing population.

Under today’s massive immigration, this will continue. Migrants primarily go to Sydney, Melbourne, other cities. Makes sense.

Kohler’s third problem is “State and Local Governments”.

“Federal government and banks encourage demand for [real estate]”, he writes, “state and local governments restrict supply.”

“In 2018, researchers at the RBA figured out that zoning restrictions raised the average price of detached houses by 73% in Sydney, 69% in Melbourne.”

This fanciful claim doesn’t pass the pub (or research) test. Co-author Peter Tulip has since shown his true colours. As a pugnacious “think” tank hawk for mega migration.

Agreed, there’s room for more medium density closer to city centres. Sure, it’s not easy for individual builders to win planning variations.

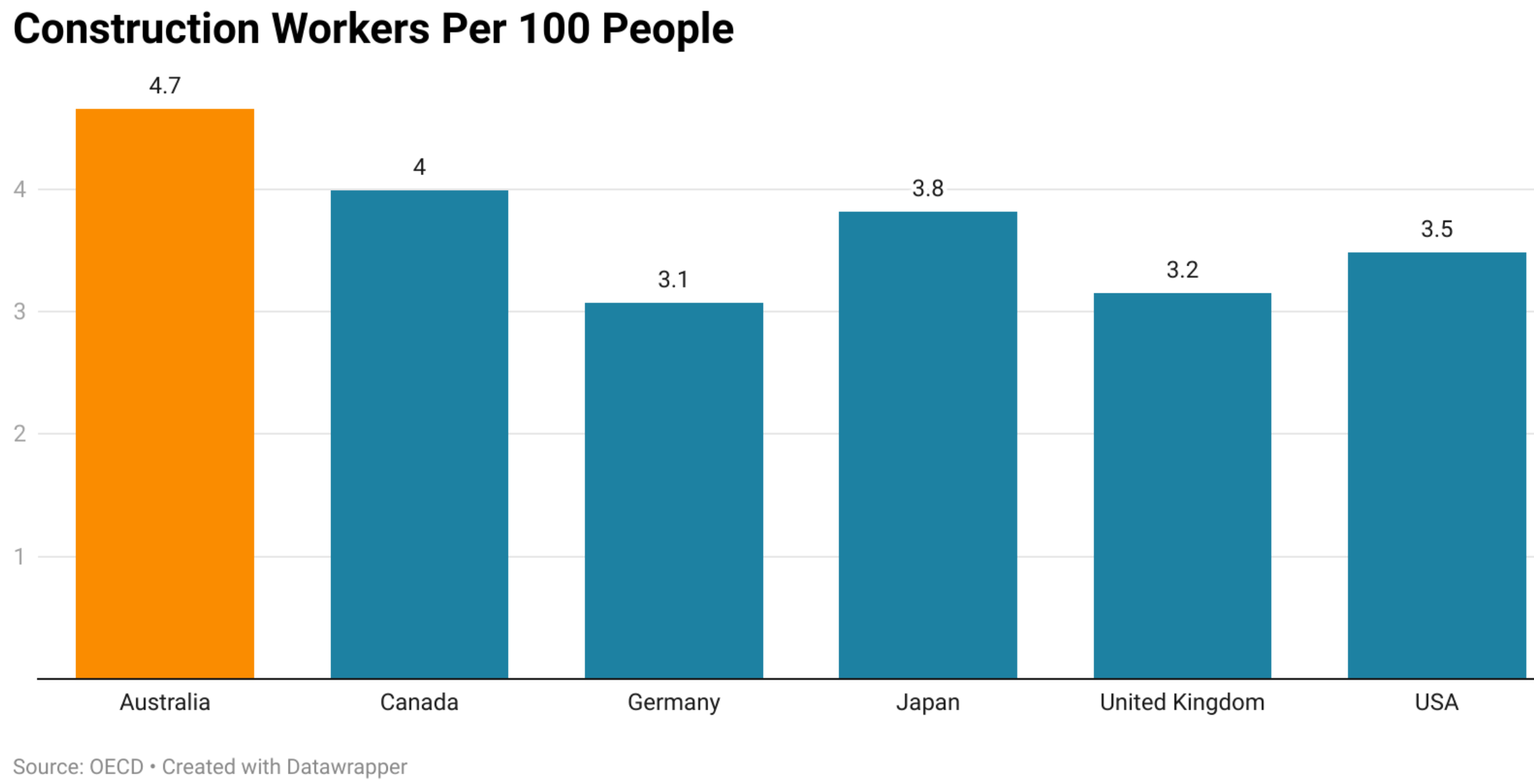

But, by OECD standards, Australia is already a champion home-builder.

Chart by Tarric Brooker

Unfortunately, also a champion land banker. In concluding pages, Kohler acknowledges this developer “cartel” as a big problem. “Involving” the toothless ACCC won’t help.

Demand side analysis

In 1994 Bob Hawke let slip the implicit pact to sequester immigration policy for politicians not voters. But 2000 is Kohler’s ground zero for the “explosion” of housing demand.

John Howard leads out Kohler’s blame game. Halving capital-gains tax, in 1999. On top of Hawke’s (1987) reinstatement of negative gearing. Labor in 2016 (and 2019) failed to wind back gearing.

Second factor is Howard’s 2000 decision to restart first-home buyer grants. These lumber on, despite “incontrovertible evidence” they don’t work.

Third comes, falling RBA cash rates over 2001-2003. Pushing investors from “shares to property”.

Kohler lambastes the 2-3% inflation target. It’s zombie RBA policy, conceived thirty years ago, when interest rates were much higher.

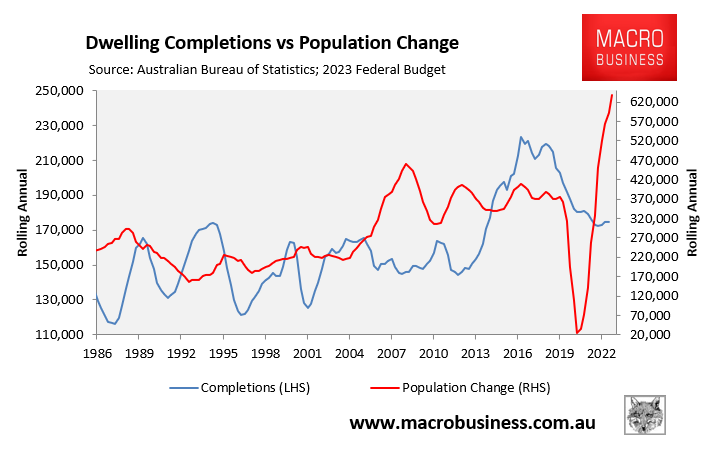

Final Kohler factor: “Between 2003 and 2009, net migration tripled, but Australia’s new open door was not matched by supply of new houses”.

Then check Figure 11. In 2023, Albanese pushed population-increase way past half a million. Just as dwelling completions slumped.

Kohler underplays our post-COVID immigration deluge.

It’s worse than Big Australia, as passed through six PMs since Howard. It’s Huge Australia.

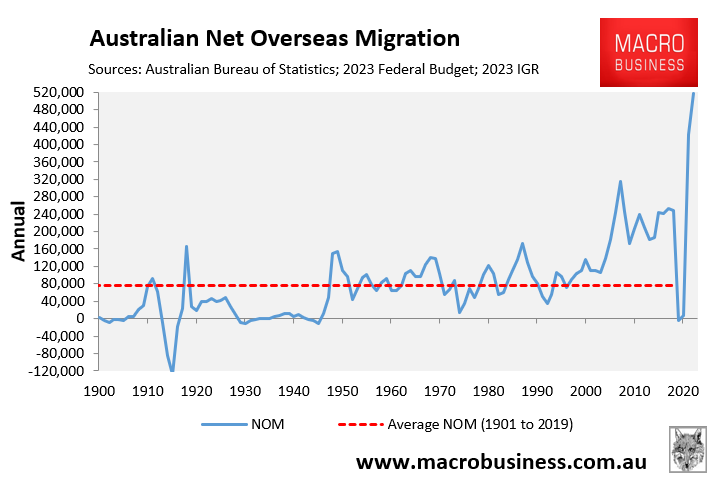

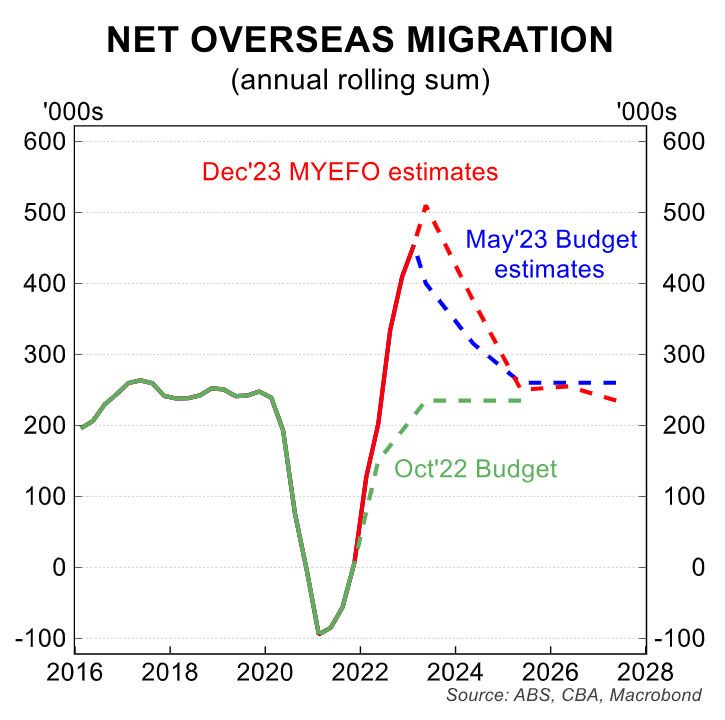

Stats confirm this. Under COVID “governance”, 2020-21 net migration was negative 85,000.

Under Morrison in 2021-22, it boomeranged a quarter million, to plus 171,000. Under Albanese, in 2022-23 it officially hit 518,000 in 2022-23. That’s a new record, by a gaping margin:

It has accidentally-on-purpose pulverised the October 2022 Budget estimate, by a quarter million, and by 450,000 over the forward estimates.

Treasury’s May 2023 Budget estimate for 2023-24 of 315,000 was another big lie. Now it’s suddenly “revised” to 375,000, but even that may be overrun.

In Albanese Australia, in order to halve migration, first you must double it.

The Kohler solutions

As Kohler notes, 65% of dwellings are still owner-occupied, 35% rented. As if two-thirds of us favour “restricting the supply of houses”.

Nonetheless, government should aim to return house prices to “three to four times average incomes”. That’s laudable.

The only way to do that, he reckons, is to keep house prices static for 15-20 years as incomes catch up.

You’d want to “limit negative gearing to newly built houses” and cut “capital gains discount to 25%”. Okay.

Then cap migration at “two-and-a-half times the number of housing approvals”.

Here, 2.5 denotes average household size. It’s hard to see a compelling remedy in tying immigration to housing approvals.

That metric – this essay generally – discounts environmental and infrastructure costs of urban population growth.

It also ignores the fact that not all dwelling approvals are completed. Nor that a significant share of new homes built are merely replacing homes that have been demolished.

As does Treasury policy. “Huge Australia” followed our driest year ever, then bushfires and floods, then the pandemic.

For a fragile continent, here’s a better metric: Migration being by far our main population builder, gradually pare it to 0.3% of population.

That would be roughly 80,000 – the historical average.

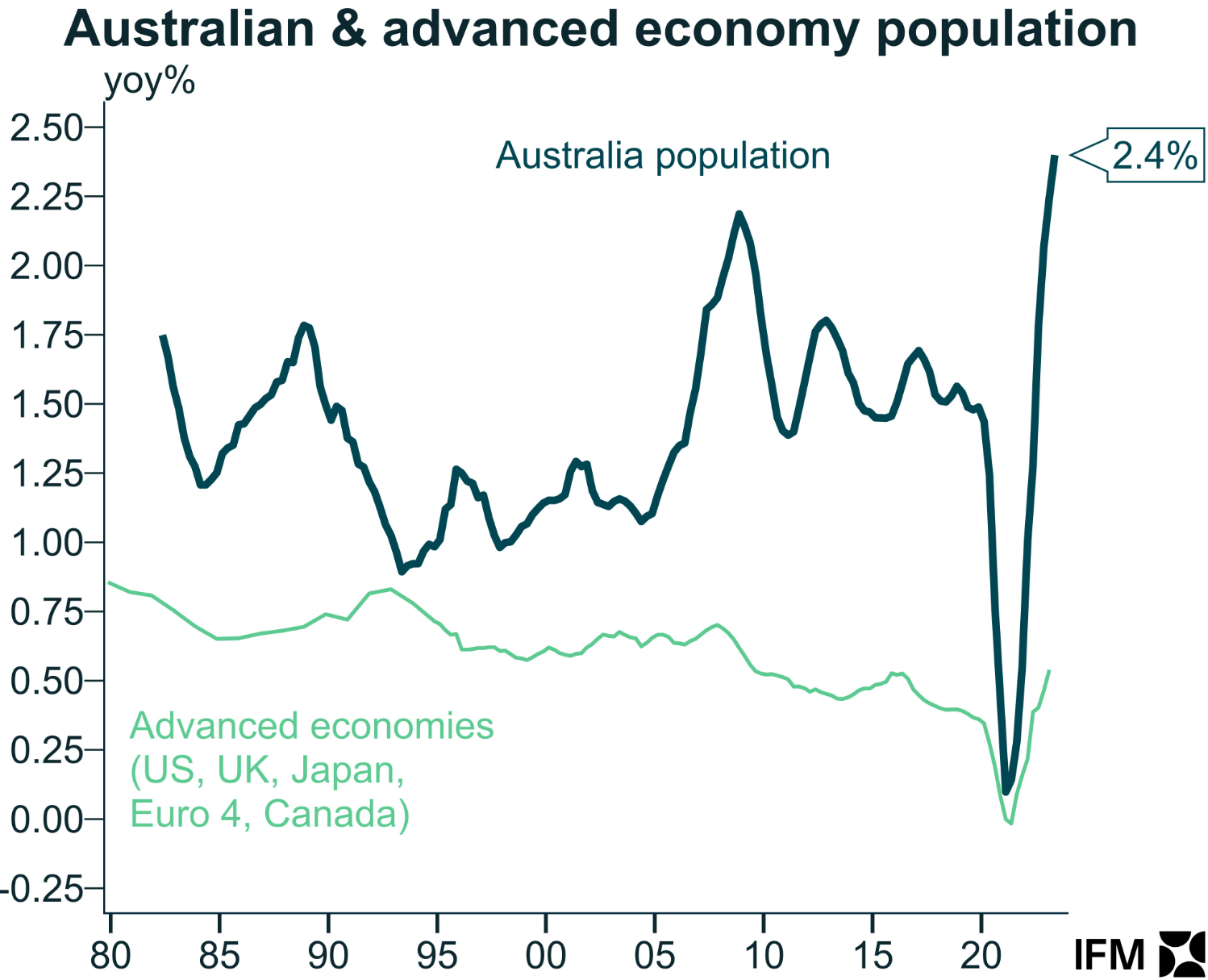

By contrast, Albanese-style immigration is 1.5-2% of population. Madness. Among major nations, “liberal” Trudeau Canada is the only comparable onslaught.

For the OECD bloc, population growth is less than 0.5%.

Most wealthy nations ignore Australia’s “economic miracle”. In effect, our recipe is for widening inequality, lowering living standards, increasing housing distress.

Kohler’s final pages revert to zoning issues, urging a “more permissive and faster planning system”. Also, he wants “trains, fast ones, lots of them, radiating from the CBDs”.

It’s too little too late.

He characterises Sydney and Melbourne as “young” cities. They’re already five million plus. Big, even by US-EU standards. Once you set aside mega-cities.

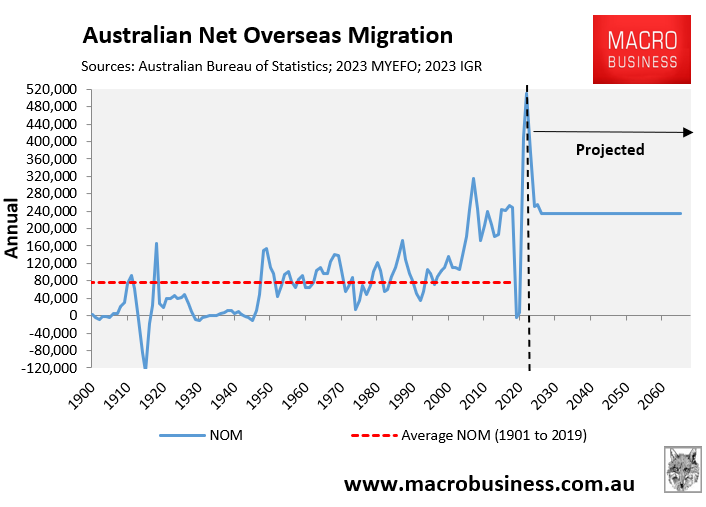

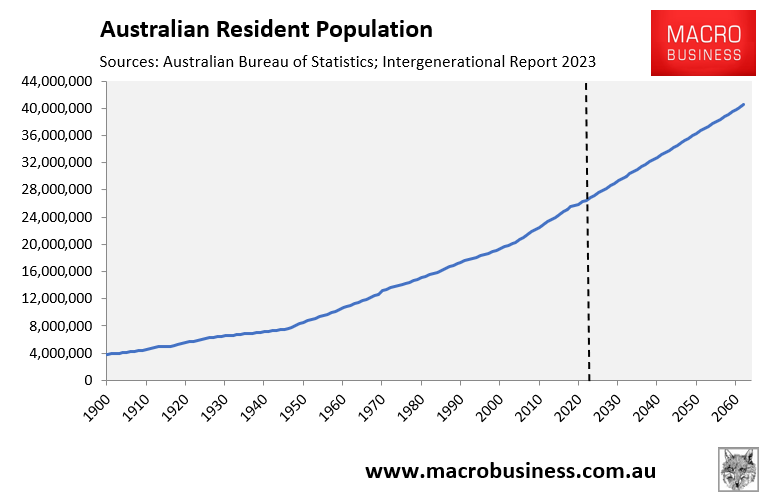

Yet, in Treasury’s draconian “intergenerational” plan, annual net migration is 235,000 forever:

That means, Australia’s population ballooning to 40 million, over the next 40 years. Sydney and Melbourne are staring at eight million apiece, around mid-century.

For average inhabitants, especially improvident souls neglecting to BYO BMD, these are already underserviced and overstretched cities.

Catching up on urban planning and infrastructure is just pious persiflage. More so, under Huge Australia.

Shameless transit schemozzles, like Melbourne’s Suburban Rail Loop or Sydney’s Rozelle Interchange, will continue to be Situation Normal.

Only in Australia, would the Albanese-Barr 1.7km Canberra Light Rail extension gobble up eight years. The first 12km took three. A fluke.

“Unaffordable housing has a political cause and a political solution,” concludes Kohler, “but victims don’t have enough political clout to make it happen.”

They also have zero clout on mega migration. Hence, Kohler’s final page is disconcerting.

“Serious government intervention” is required to make housing affordable “compared to incomes”. Copy that.

Rather than augmenting the “room full” of inquiries, “we just need a task force drawn from the Treasury and the housing department”.

Alan – you’re kidding.

Our Treasury itself gives the gift of housing crisis, also a population crisis. Exacerbated, by their May 2023 Budget and the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

On housing, retaining deluxe investor-incentives for cashed-up locals and migrants. For voters, the derisory Accord promise of a million (now 1.2 million) homes over five years.

On population, a massive 715,000 (already a big undercount) net-migration over 2022-24. No informed rationale, no voter consent. As politicians cosplay over 140 detainees.

On environment, sops of “better protection”. Alongside trendy gestures of “renewable energy superpower” and “net zero industries”.

21st century Treasury dictates housing unaffordability. No mere Treasurer will unpick that.

Recently, I pitched five circuit-breakers for Huge Australia which might, in turn, give housing affordability a slim chance.

These were: “stakeholder” insurgency, escalating “natural” disasters, an exceptional leader, civil unrest, and international pressure. But we’d need another Curtin.

Over 25 years, cynical politicians have embedded housing unaffordability. Their “democracy of donors” would like another 25.