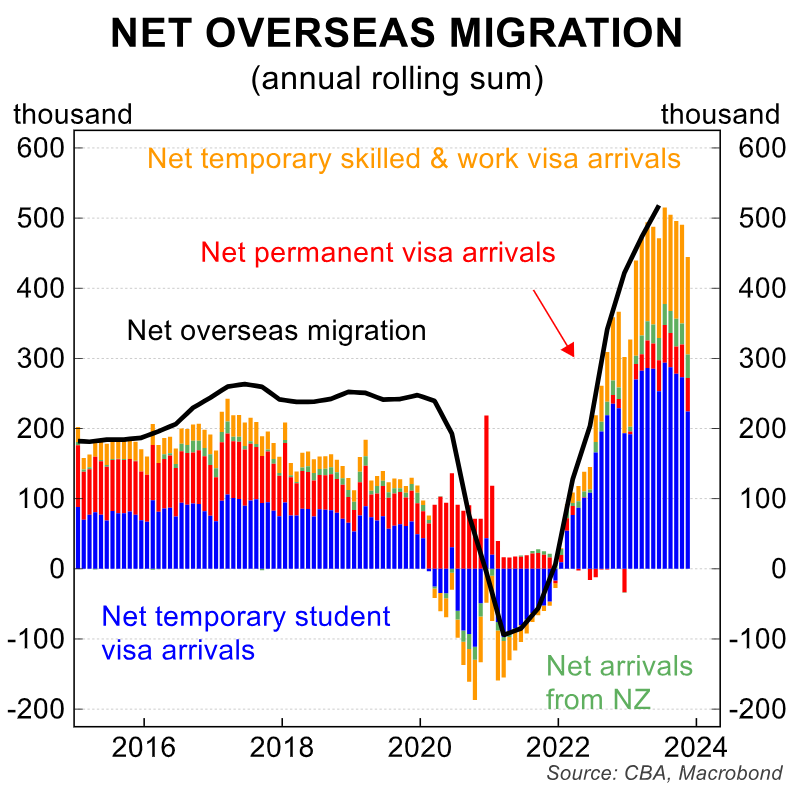

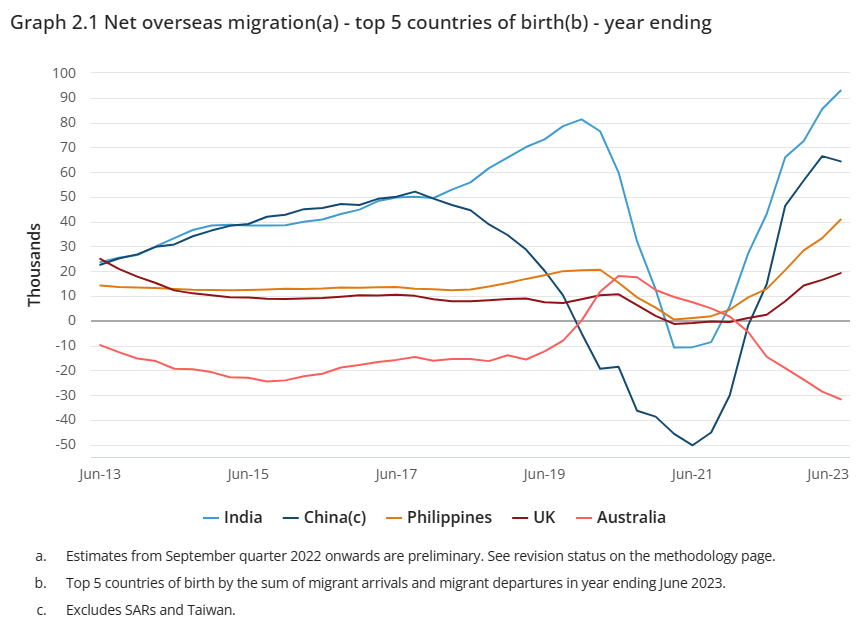

Indian students are one of the driving forces behind Australia’s current record net overseas migration.

After the former Coalition Government abolished the cap on international student work hours and prolonged the length of time VET graduates could stay in Australia after they finished their studies, the number of Indian students arriving for work and residency exploded.

The Albanese government then increased the permanent migrant intake to record levels (increasing the likelihood of students obtaining permanent residency), extended post-study work rights for international university graduates (rescinded this month), and signed migration treaties with India, which promises five-year student visas and eight-year post-study work visas.

These policy changes have been a ‘red rag to a bull’ for non-genuine Indian students, shady education agents, and scam ‘ghost colleges’, which have proliferated.

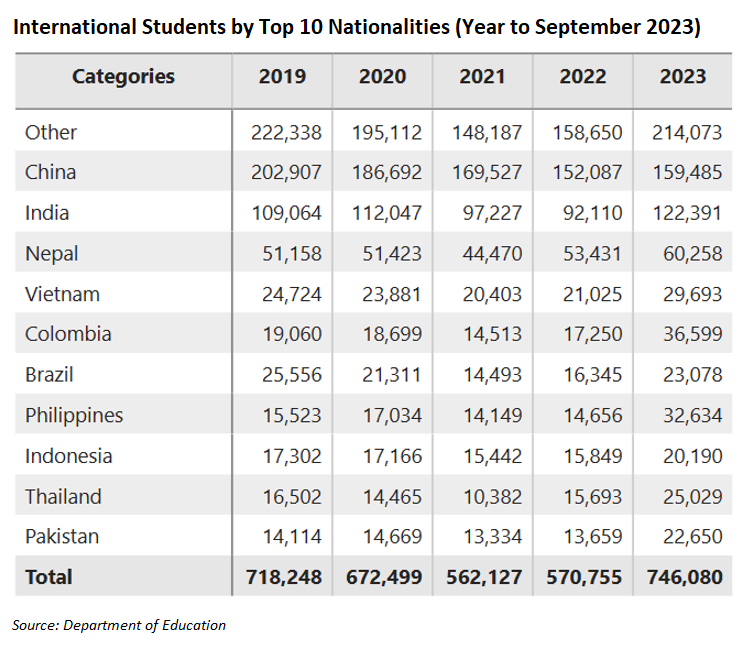

Australia now has its largest-ever intakes of Indian students in universities and vocational programs, as well as on post-study work visas.

This sparked concern among universities, with at least seven institutions this year prohibiting students from several large Indian states.

Phil Honeywood, CEO of the International Education Association of Australia, warned this year that Australia’s international education system has degraded into a “Ponzi scheme” for recruiting non-genuine students through migration channels (here and here).

This echoed the claims of Labor’s federal member for Bruce, Julian Hill, who stated that Australia’s international education industry had devolved into a “Ponzi scheme” by enticing international students with easy employment rights and permanent residency.

With this recent history in mind, it is disturbing to read that outgoing university lobby chief, Catriona Jackson, is urging Australia’s higher education sector to target students from Africa.

“We’ve built up a really good education system that serves our domestic population but also a really big international cohort, so we just need to absolutely stay right on the front of the wave, otherwise we will be dumped”, she said.

“I think we absolutely need to be looking at Africa because that’s where the explosion of working-age people is”.

“So it’s our job as countries who have one big asset here, a really strong education system, to make sure we’re providing that in the best possible way”, she said.

According to a recent Navitas survey on study intentions, students from India and Africa choose a location based on their capacity to gain work rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency:

South Asia and Africa students care about working and migration, not education quality.

In contrast, students from these two countries care least about educational quality.

Instead of further lowering standards to attract African students, policymakers should focus on attracting a smaller pool of excellent (genuine) students by raising financial barriers to entry, increasing entrance requirements (particularly for English language proficiency), and removing the clear link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

These reforms would improve student quality, increase export income per student, elevate wages and working conditions in lower skilled jobs, and reduce enrolment levels to manageable and sustainable levels, hence increasing quality and learning environments for local students and relieving population pressures.

To put it another way, international education should prioritise quality above quantity.

Otherwise, Australia will experience a recurrence of what happened last decade, which saw widespread youth unemployment, wage theft, exploitation, and overcrowding in housing and infrastructure.