In August, Australia’s National Cabinet signed off on a target to build 1.2 million homes over five years to alleviate the nation’s housing shortage.

This target will require 240,000 homes to be built each year for five straight years.

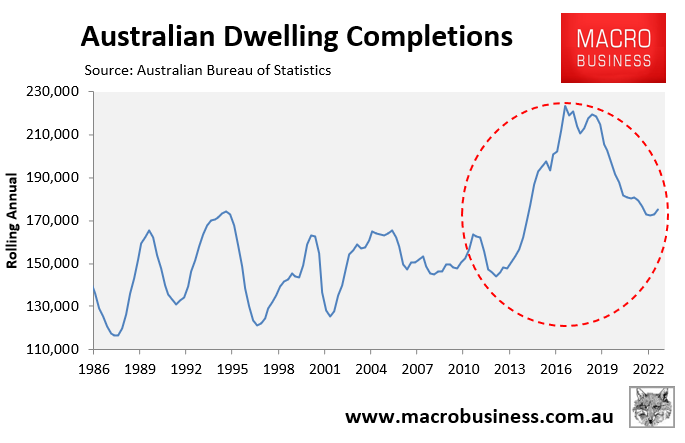

Nobody actually expects this target to be met, given Australia’s record for new home construction was around 223,000 in 2017:

This record result was achieved with considerably lower interest rates, cheaper materials prices, and fewer labour force constraints.

This construction was also concentrated in low-quality high-rise apartments, which ended up being riddled with flammable cladding and defects, which will cost billions of dollars to rectify.

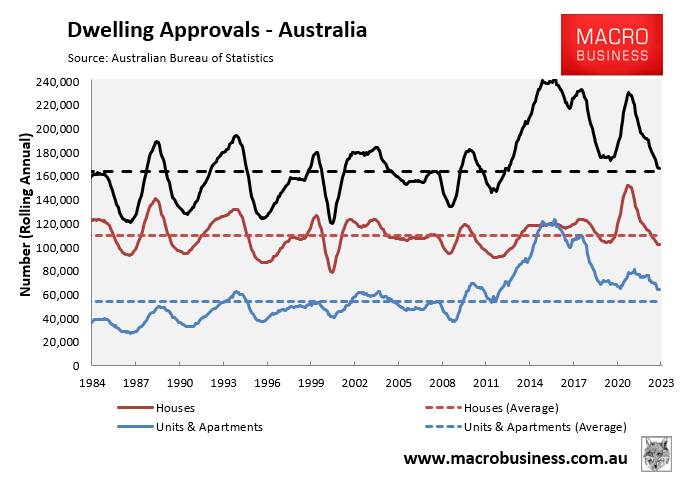

Indeed, forward-looking indicators of housing construction are poor.

The ABS’ dwelling approvals data shows that only 164,200 homes were approved for construction in the year to October – the lowest level in a decade:

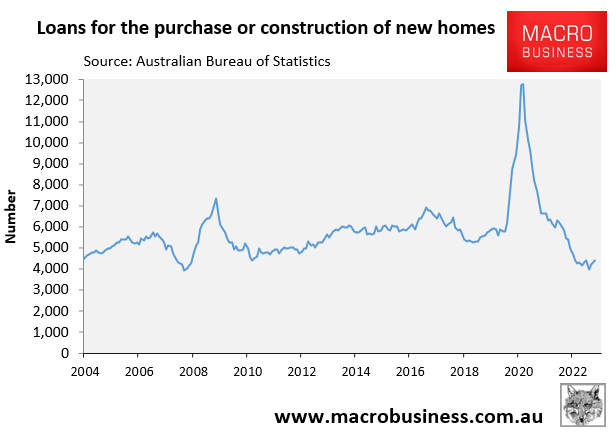

Loans for the purchase and construction of a new home are also tracking at historical lows, according to the ABS:

Nevertheless, former Victorian Premier Dan Andrews committed to an even larger housing construction target.

In one of his final acts as premier, Andrews issued a major housing statement setting a goal of 800,000 new homes – 80,000 per year, or 220 per day over the next ten years – and 2.24 million new homes by 2051.

This eclipsed Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s target of 1.2 million new homes over the next five years.

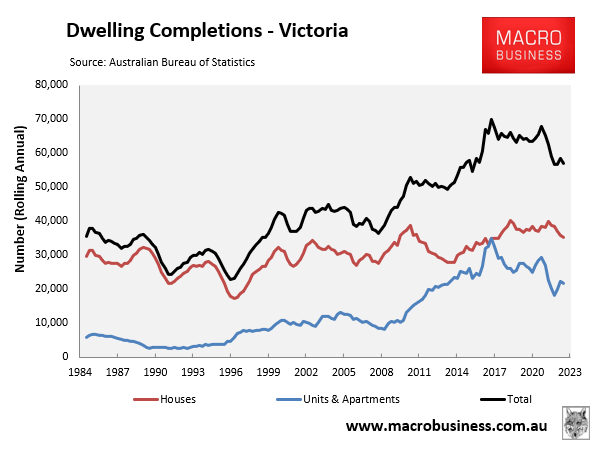

As shown in the next chart, Victoria built only 57,000 homes in 2022-23, and has never built even 70,000 homes in a single 12 month period:

Therefore, the notion of building 80,000 homes a year for 10 years straight is delusional.

It is even more unrealistic when the state government is sinking all of its construction resources into its Big Build projects, which is hoovering up available workers and materials.

According to Builders Collective of Australia president Phil Dwyer, the residential construction industry is in poor shape and large-scale construction projects are more appealing to tradies:

“It’s had a big impact and that, of course, has impacted on the program of building all these houses that the government has targeted. We’ve got no hope in the world of building or meeting those targets”, he said.

“It drives up the cost of labour but more importantly, we don’t have enough tradies within the building industry to be able to build these homes”.

Housing Industry Association Victorian executive director Keith Ryan warned that members were struggling to recruit workers because of the competing sources of employment – a situation that will worsen in 2024.

“The only thing that makes it less of an issue than it could be is the fact that we’ve got a big slowdown in new-home starts coming through”, he said.

Meanwhile, the Property Council’s Victorian executive director, Cath Evans, said the sector was experiencing a pronounced shortage of construction workers, which was driving up housing costs.

“This shortage is having a noticeable inflationary impact on the cost of delivering residential projects, which has a flow-on effect on the affordability of housing for Victorians”, she said.

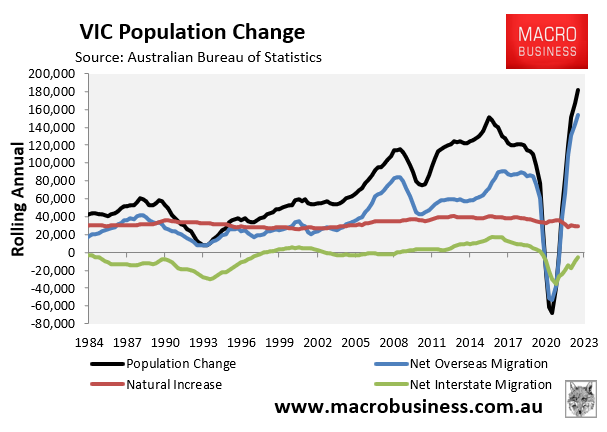

The primary problem is that Victoria’s population has grown like a science experiment courtesy of the federal government’s mass immigration policy:

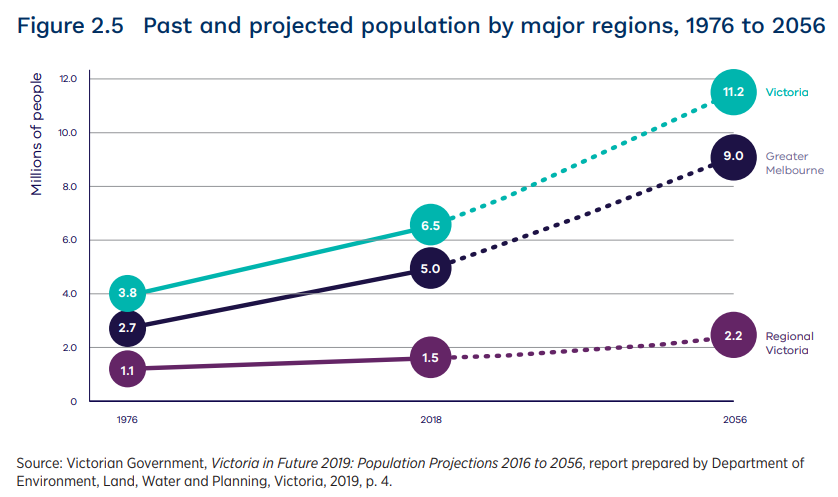

Victoria’s population is also forecast to swell to 11.2 million people by 2056, with Melbourne’s population projected to hit 9.0 million people:

This massive increase in population will require huge sums of infrastructure and housing if the state is to avoid becoming crush-loaded and its residents homeless.

The obvious solution is to run a moderate immigration program commensurate with Victoria’s (and Australia’s) capacity to build new homes and infrastructure, as well as safeguard the natural environment (including water supplies).

Otherwise, the nation faces never-ending shortages of everything, along with lower living standards.