Gareth Aird, head of Australian economics at CBA, has published a terrific analysis of the latest batch of key economic data, which shows the economy has lost momentum.

The RBA’s aggressive rate hikes are now biting, and Aird believes that Australia’s unemployment rate will rise materially in 2024 amid the slowing economy.

Accordingly, the RBA has very likely finished with interest rate hikes and is more likely to cut rates in the second half of 2024.

Key Points:

- Economic growth stalled in the September quarter and the labour market has clearly turned.

- The economy is contracting significantly on a per-capita basis, which means economic growth is running well below trend.

- We expect the labour market to loosen more materially from here as the consumer continues to soften.

- Pressure on wages growth will ease as the jobless rate lifts and inflation further moderates.

- Against this backdrop we think that it would take a ‘material’ upside surprise in the Q4 23 CPI for the RBA to raise the cash rate in February 2024.

- We remain comfortable with our base case for an easing cycle to commence in September 2024

Weak economic growth means rising unemployment:

The Australian economy is slowing more quickly than the RBA anticipated in November when it published updated economic forecasts in the Statement on Monetary Policy.

Domestic economic data that printed between the November and December Board meetings did not support the case for back-to-back rate hikes.

And since the December Board meeting key economic releases indicate that policy on hold in December was very much the right decision.

The Q3 23 national accounts were a softer set of figures than the RBA had anticipated, particularly on the consumer side.

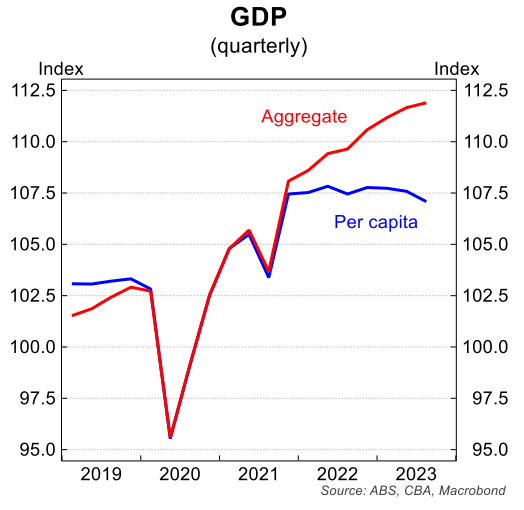

GDP growth is well below trend. The six-month annualised pace of GDP growth to the September quarter slumped to 1.3%.

This compares with population growth of ~2.5%/yr. The upshot is that the economy has gone backwards for three consecutive quarters in per capita terms (see below chart).

The slowdown in the economy is by design and not default. The RBA raised rates to a restrictive setting to see economic growth slow to a below-trend pace.

That in turn puts upward pressure on the unemployment rate and downward pressure on inflation. The process is working. It just takes time.

Monetary policy is clearly restrictive:

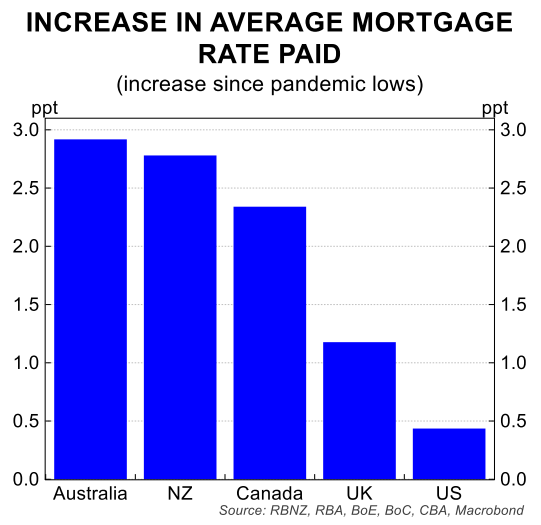

There has been debate about how restrictive monetary policy is in Australia. This is particularly the case given our policy rate is lower than many other comparable jurisdictions.

We have consistently made the case that the RBA did not need to raise rates as high as many of the other major central banks because the transmission channel to mortgage holders is much more direct (see below chart). In addition, Australian households are more highly leveraged.

The RBA themselves have questioned just how restrictive policy is in Australia.

In the November Board Minutes it was noted that, “housing prices were continuing to rise and loan approvals had increased over prior months, both of which might indicate that financial conditions are not especially restrictive.” (our emphasis in bold).

It could also be argued that aggregate demand has held up reasonably well. And until recently the labour market had not shown signs of loosening sufficiently.

But strong population growth has masked weak per capita outcomes. And it was only a matter of ‘if’ and not ‘when’ the labour market data would catch up to the material slowdown in GDP growth.

Households are stretched:

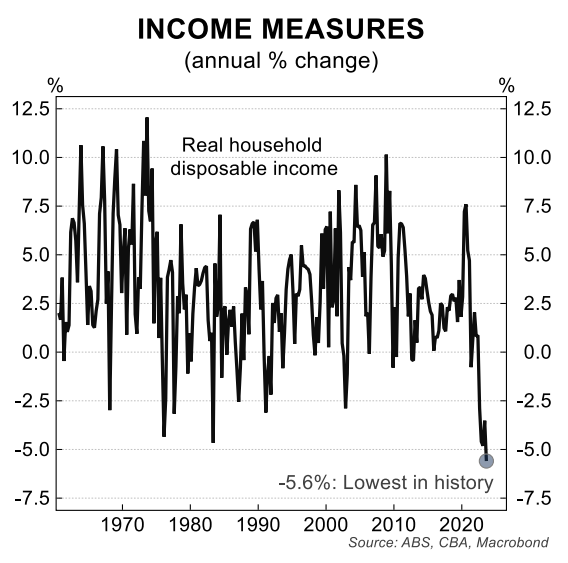

Many households are financially stretched. Real household disposable income declined by 1.7% in the September quarter to be 5.6% lower over the year.

Indeed real household disposable income has fallen by 8.3% since its peak in Q3 21.

The 5.6%/yr fall in real household disposable to the September quarter was the biggest decline on record (the national accounts go back to 1959).

Interest paid on housing debt is up by 70.6% over the past year ($A12.3bn) and a massive 173.3% from pandemic lows. And income tax payable is up by an astonishing 23.4%/yr ($A17.2bn).

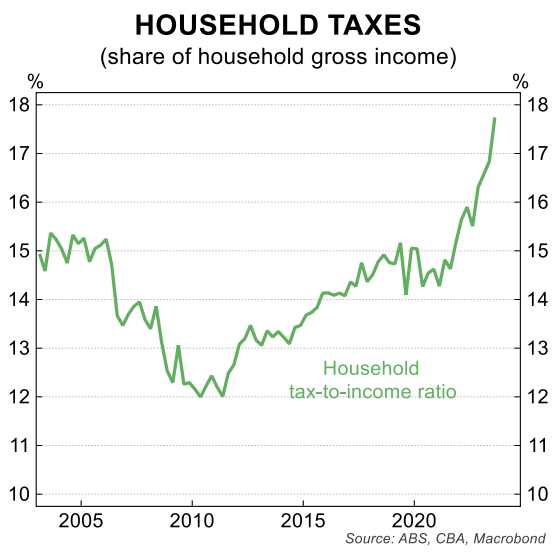

Fiscal drag (otherwise known as bracket creep) is seeing an increasing share of households hand over a larger share of their income to the Commonwealth Government.

In Q3 23 households handed over a record share of income to the government as taxes paid.

The upshot is that consumer sentiment is in the doldrums. And household consumption per capita is very weak (down by ~2.2%/yr in Q3 23).

The labour market has until recently been resilient against a weakening economic backdrop. But cracks are now becoming more obvious.

Unemployment rate now on a clear upward trend:

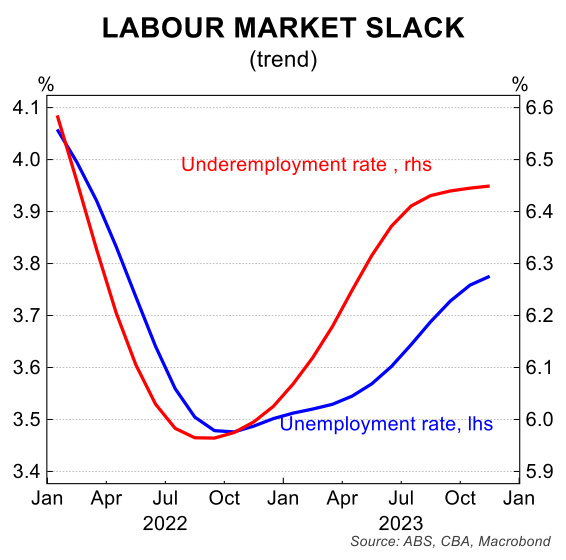

The unemployment rate increased in November to 3.9%. The jobless rate is 0.4ppts above its cyclical low. A trend lift in the unemployment rate is now clearly in train. And underemployment is also on a gradual march higher.

The big 61.5k lift in employment in November was a surprise. But it was accompanied by a spike in the participation rate.

A greater share of a rapidly growing population is being dragged into the workforce given the strain on household budgets.

From a monetary policy perspective, the unemployment rate is the key metric of the labour market. And its rise indicates the labour market is loosening.

The trend in hours worked is also worth closer inspection. Hours worked have moved down over the past six months. That indicates the demand for labour has cooled.

As the ABS aptly stated this week, “the slowing in hours means that overall growth rates in employment and hours worked are now similar over the past 18 months. The narrowing gap between these two growth rates suggests that the labour market is now less tight than it has been.”

Other second tier labour market data also paints a clear picture of a loosening labour market.

Seek jobs ads were down by 4.3% in November to sit 20.2% lower over the year. They are still above their pre-pandemic level. But the direction of travel is clear.

The number of applicants per job ad continued to march higher in October (latest available). Applicants per job ad are up by 82.8% over the year.

Monetary policy is clearly working to slow the economy. And the proverbial ‘long and variable’ lags mean that the impact of tightening is more obviously kicking in now.

The RBA will continue with their inflation fighting rhetoric for some time. But against the backdrop of rising unemployment and falling GDP per capita, the Board will be quite reluctant to tighten policy further.

Indeed, the need for further rate rises has dissipated.

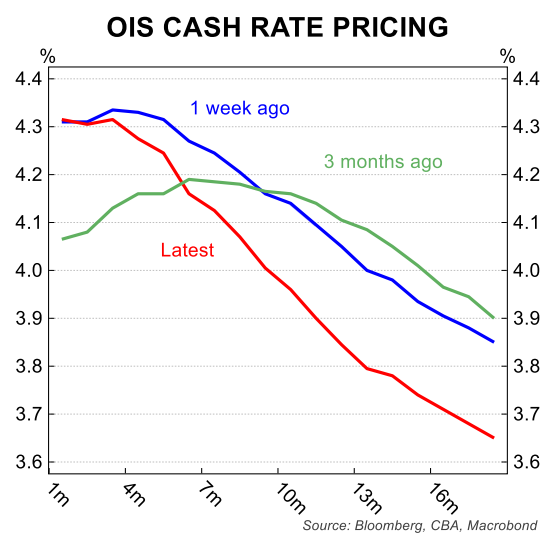

As we go to press markets agree that recent incoming economic data does not make the case for more policy tightening. Markets have priced that the next move in the cash rate is down. And we agree.

Indeed markets have now fully priced a 25bp rate cut by September 2024 – the time at which we expect the RBA to commence their easing cycle.

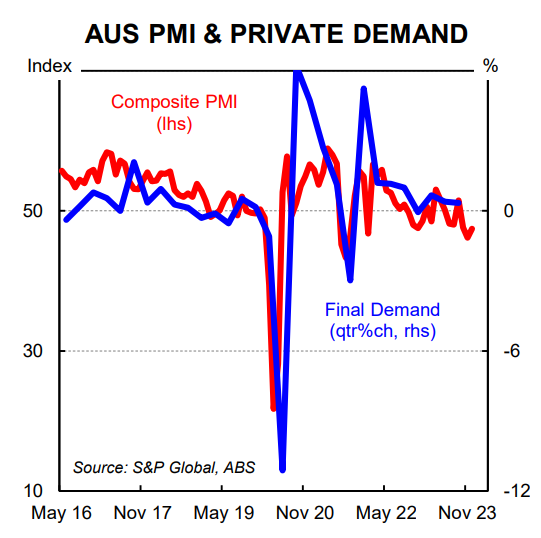

The data calendar for the rest of 2023 is light. There are no local releases that will move markets. But it’s worth noting that the Judo ‘flash’ PMIs were released Friday for December.

The Composite PMI was 47.4 in December – a level that indicates private output contracted over the month. The PMI has printed below 50 for the past three months.

A ‘nowcast’ of Q4 23 GDP suggests we may see an outright contraction in GDP over the quarter.

The last key event for domestic market participants is the RBA December Board Minutes, to be released next Tuesday (19/12).

We expect the Minutes to indicate the Board debated the case to raise the cash rate in December or keep policy on hold.

The pros and cons for changing policy will be stated. But ultimately we think the decision to leave the cash rate on hold in December will have been a straight forward one. The recent data rubber stamps that was the correct policy choice.