By Gareth Aird, head of Australian economics at CBA.

Key points:

- Personal income tax cuts worth 0.8% of GDP will kick in from 1 July 2024.

- The Government will change the distribution of the previously legislated Stage 3 tax cuts, but the size of the expected tax cut in 2024/25 is little changed.

- Income tax paid as a share of household income will continue to rise and will push new record highs over the next few quarters before the tax relief arrives.

- The changes to the tax cuts are not material enough for us to modify our economic forecasts.

- Our base case remains that the RBA will commence an easing cycle in September.

A recap of the proposed tax changes:

Last week the Commonwealth Government announced changes to the already legislated Stage 3 tax cuts. The Government’s remodelled tax plan will need to be passed by the Senate before coming into effect. We see this largely as a done deal.

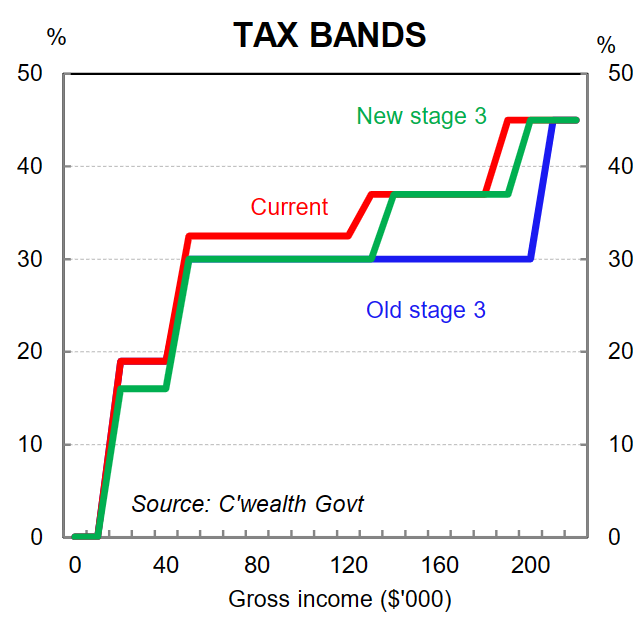

The new tax cuts are broadly similar in size over the next few years to the previously legislated tax cuts (a touch larger at the margin). But the key difference is around the distribution of tax relief.

The changes mean that more individuals will receive a tax cut from 1 July 2024.

Specifically, the Government estimates that 13.6 million taxpayers will receive a tax cut, compared with 10.7 million taxpayers under the previous arrangements.

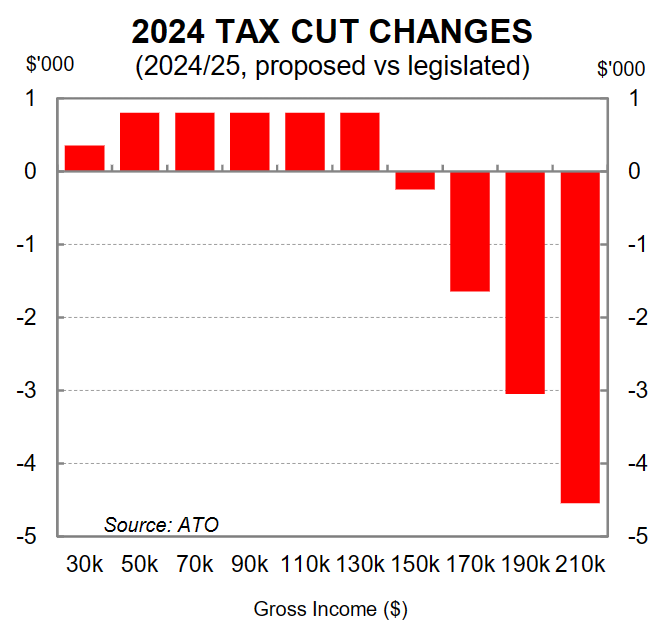

The new tax cuts result in a smaller share of tax relief going to higher-income earners. Low and middle-income earners now receive a larger portion (see below chart).

Importantly, the overall size of the tax-cut pie is little changed over the next few years. This is of primary significance when assessing the impact of the changes on the outlook for the economy and the RBA.

Our economic forecasts and RBA call factored in the already legislated Stage 3 tax cuts. We used a working assumption that ~80% of the tax relief would be spent (~$A16bn). That may seem high given the majority of tax relief was due to flow to higher income earners who generally have a lower marginal propensity to consumer (MPC) than lower income earners.

But given the squeeze on real household incomes at present, we thought it prudent to opt for a larger number.

A case can be made that a greater share of the income tax cuts will now be spent than we previously assumed given the skew has shifted towards lower and middle income earners.

But the overall changes are not enough to shift the dial for economic growth, the labour market or inflation.

For example, if we now assume that all of the tax relief is spent due to the distributional changes of the tax cuts, the additional consumption relative to our forecasts is just ~$A4bn or 0.15% of GDP a year ; a rounding error in a $A2.6tn economy.

Importantly, changing the spending assumption has no discernible impact on our inflation forecasts.

We do not wish to trivialise the tax cuts as they are significant in size. But the above back of the envelope calculation highlights why we do not think the Government’s new tax plans warrant a change of economic forecasts.

In any event, the bigger picture matters. The tax cuts are only a partial offset to the massive lift in income tax paid as a share of household income over recent years.

As a result, we do not believe they are sufficient in size to fend off RBA rate cuts later in the year.

Tax paid as a share of income will continue to lift until 1 July 2024:

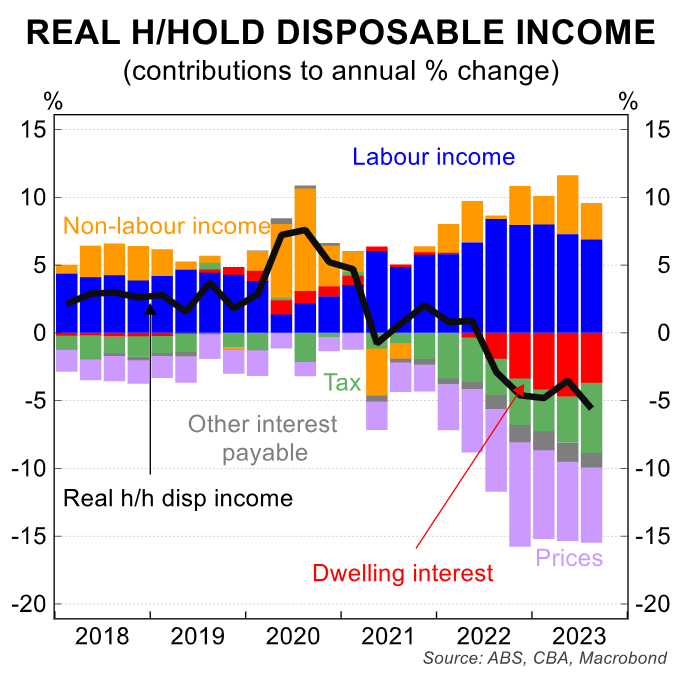

The impact of the RBA’s aggressive rate hiking cycle on household income and by extension consumption has been well covered. For context, interest paid on housing debt has surged by 70.6% over the year to Q3 23 and a massive 173.3% ($A18.8bn) from pandemic lows.

But the role that higher tax paid as a share of income has had on household purchasing power has not received as much air play. And yet the impact has been very significant.

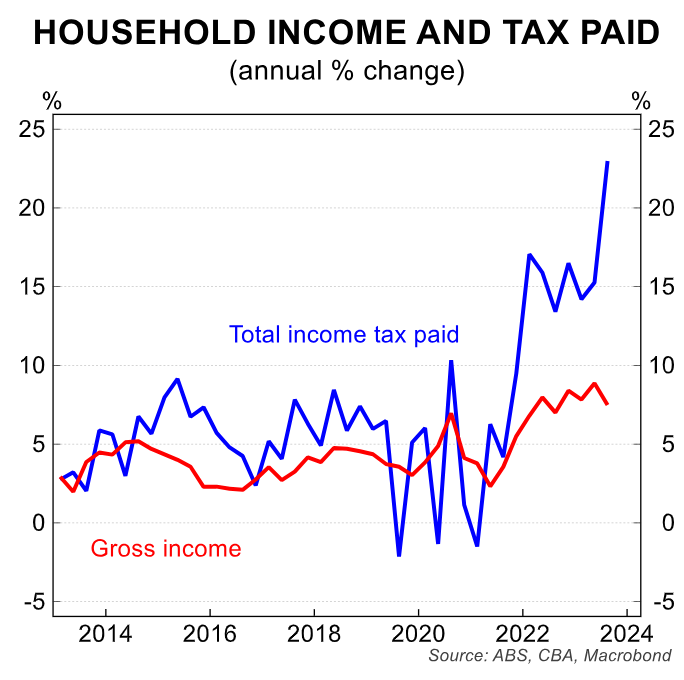

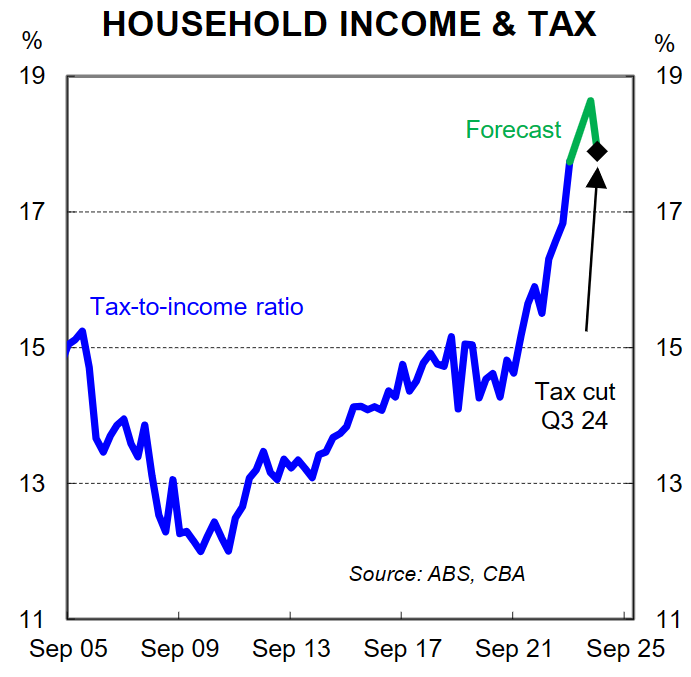

The quarterly amount of income tax payable is up by a whopping 23.4%/yr to Q3 23 (latest available). Over the same period total household income has grown by a much lower 7.5% (see below chart).

As a result, tax paid as a share of household income has risen sharply to a record high of 17.7% (see below chart). We forecast that this ratio will continue to lift to ~19% by Q2 24.

On our calculations the tax cuts that arrive on 1 July 2024 will drop the tax paid to income ratio to a still very high 18%.

Put another way, households will still be handing over a much higher proportion of their income to the Government than they were in 2022 and the years prior.

This is a handbrake on consumption and demand growth in the economy more broadly.

The economy will continue to slow over H1 24. And by the time the tax cuts arrive we expect the unemployment rate will have risen to ~4¼%. Inflation is also forecast to continue to fall.

The impact of the tax cuts on the economy will not be picked up in the official data until late 2024. Before that point we expect the key economic data on inflation, unemployment and GDP to print in a configuration that sees the RBA commence an easing cycle.

The RBA Board is unlikely to wait to assess the impact of tax cuts on the economy if the already-released data suggests the case for maintaining a restrictive monetary policy setting is no longer necessary or appropriate.

We therefore view the tax cuts as a risk to our call for the RBA’s easing cycle to extend into H1 25 rather than our expectation that rate cuts will commence in September 2024.

It may be the case that the RBA delivers on our expectation for 75bp of easing from September 2024 this calendar year (25bp in September, November and December).

But that policy then stays on hold in H1 25 if the tax cuts generate a bigger lift in economic activity than we currently envisage (our base case sees that RBA deliver a further 75bp of cuts in H1 25, which would take the cash rate to 2.85%).

In summary, we make no changes to our economic forecasts or RBA call as a result of the tax changes.

Indeed we expect the RBA themselves will also make no tweaks to their forecasts as a result of the Government’s modifications to the Stage 3 tax cuts.