Goldman with the note.

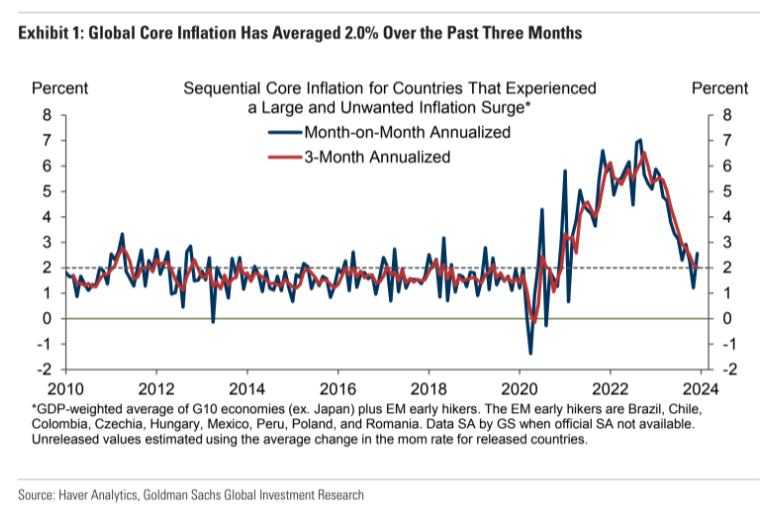

Global core inflation—averaged across the G10 ex Japan plus the EM earlyhikers—picked up to an estimated 1-month annualized rate of 2.6% in December from the rock-bottom 1.2% reading in November.

This has triggered a renewed round of concerns that the disinflation of 2023 may not last, with some arguing that it was due to a one-off improvement in goods supply—and thus a one-off decline in the level of goods prices—alongside entrenched service inflation.

We continue to take a more optimistic view.

First, the trend is still improving, as the 3-month annualized rate fell further to an estimated 2.0% in December.

Second, the adjustment in core goods prices is far from complete—for example, US used cars have only unwound 31% of their covid-related price increase.

And third, we expect both service inflation and wage growth to continue slowing gradually in a lagged response to the improved supply/demand balance across the global economy.

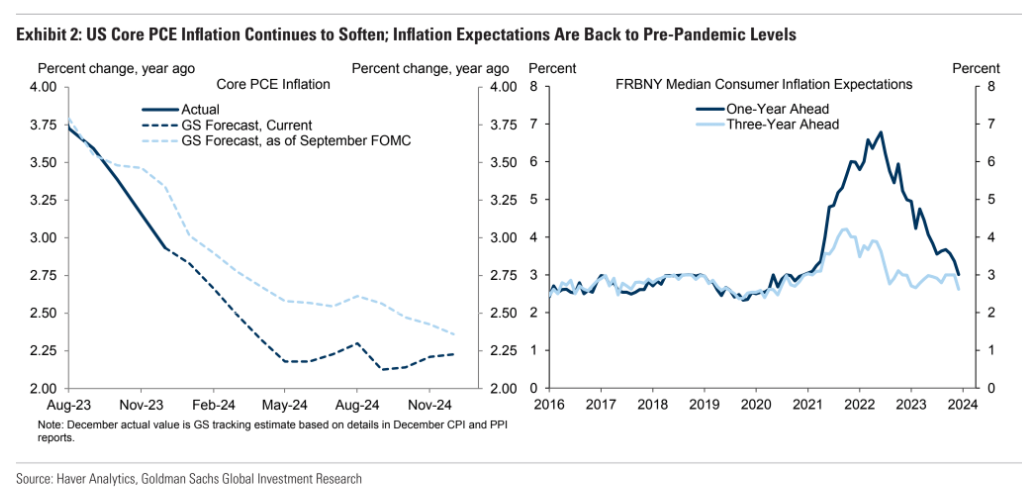

The US has fully shared in the global disinflation trend. Even with relatively pessimistic assumptions for imputed categories such as financial services and non profit organizations, we estimate that last week’s CPI and PPI imply a sequential core PCE increase of 0.17% (not annualized) in December.

This would leave the6-month annualized rate—which Fed officials have repeatedly emphasized in the lastfew months—at 1.9%.

Beyond December, we have built in a positive “January effect” worth 0.1pp sequentially (not annualized), which we expect to be unwound in subsequent releases.

This implies a year-on-year rate of 2.6% in February (up from 2.5% in our previous forecast) and 2.1% in May/June (as before).

Meanwhile, inflation expectations have declined, with both the University of Michigan and New York Fed measures falling back to pre-pandemic levels in recent months.

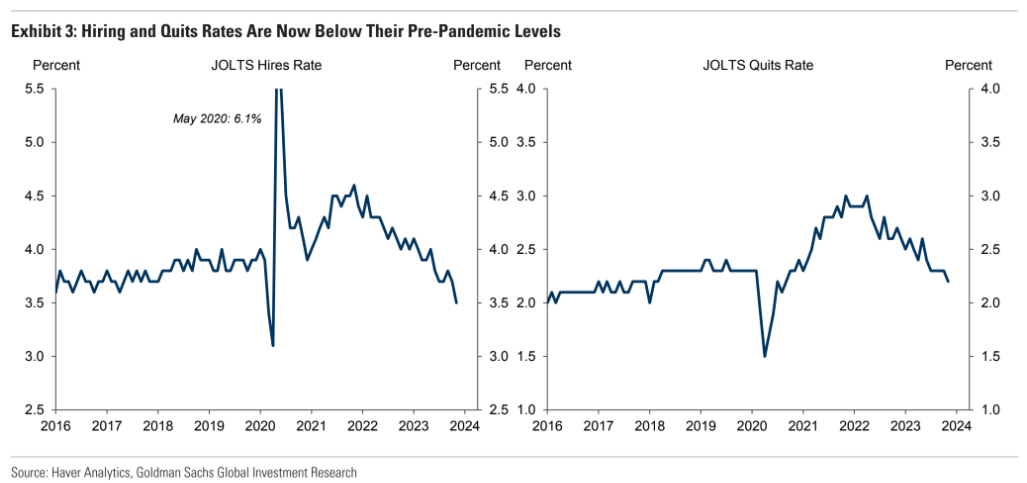

Despite low jobless claims, an unchanged 3.7% unemployment rate, and a 216knonfarm payroll increase in December, the US labor market continues to rebalance.

Both household employment and the nonmanufacturing ISM employment index fell in December, and the JOLTS hiring and quit rates are now below their pre-pandemic levels.

We would put more weight on these indicators than on the 0.4% increase in average hourly earnings in December, which we view as a temporary hiccup in the gradual downward trend of our GS wage tracker.

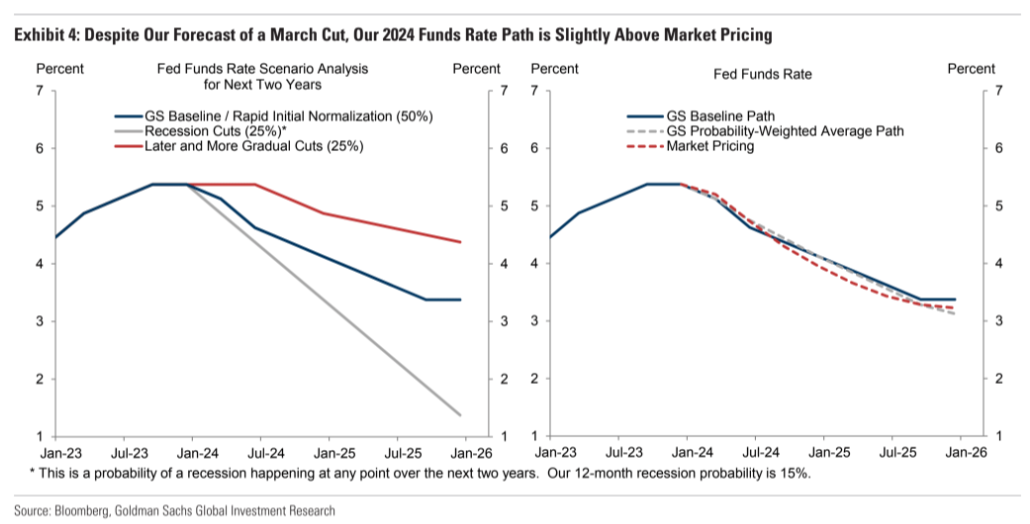

These signals leave us comfortable with our forecast that the Fed will start cutting the funds rate soon, most likely in March.

After all, Chair Powell said at the December 13 press conference that the committee would want to cut “well before” inflation falls to 2%.

However, we expect “only” 5 cuts this year, below the 6-7 cuts now discounted in market pricing, and we view the chance of 50bp steps as low.

The main reason is our optimistic view on the US growth outlook.

If we are right that US GDP will grow 2.3% (vs. a 1.3% Bloomberg consensus) and the risk of recession is only 15% (vs. a 50% Bloomberg consensus), a series of gradual adjustment cuts is more likely than an aggressive easing campaign.

There is still a good conceptual case for a growth pickup in Europe this year on the back of rising real household income and easier financial conditions, and some forward-looking activity indicators such as the ZEW expectations measure are showing a modest improvement.

But with growth still clearly below trend, we expect the gradual labor market slowdown of 2023 to broaden into an increase in the unemployment rate in 2024.

Both inflation and activity therefore signal that rate cuts are needed to rebalance the risks to the ECB’s mandate.

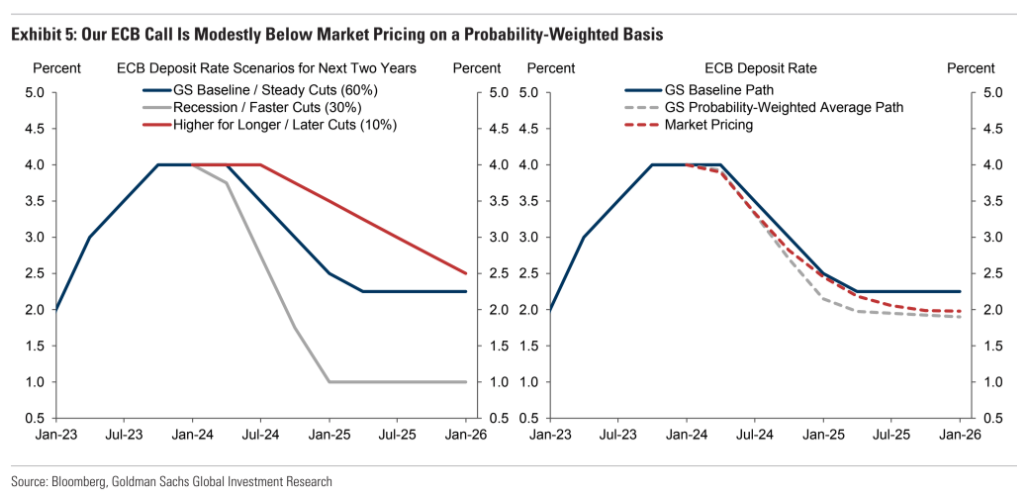

Our baseline forecast is a series of 25bp cuts starting in April, but we would not rule out an earlier start and see a 30% probability of more aggressive 50bp cuts.

Hence, our probability-weighted forecast for the deposit rate is below market pricing in late 2024/early 2025.

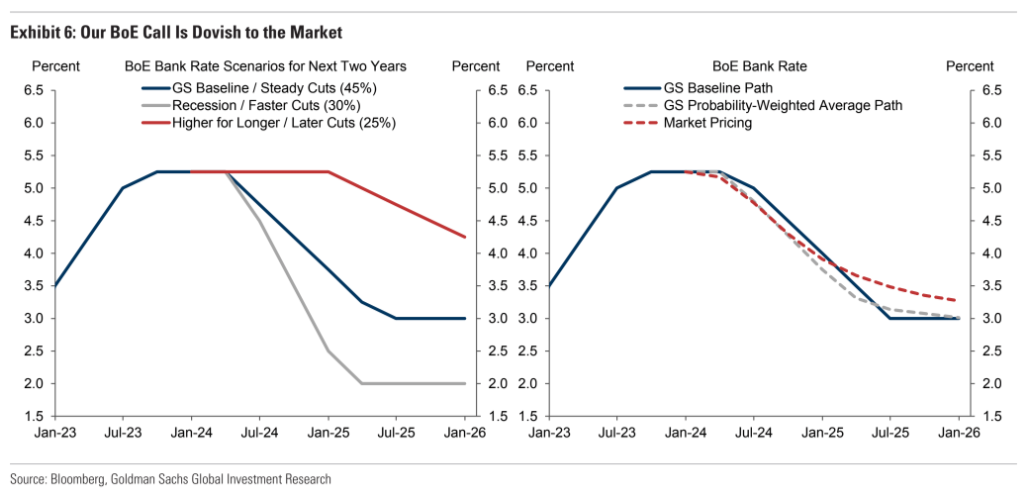

Our BoE call for late 2024/early 2025 is also below market pricing. The policy rate is 125bp higher than in the Euro area, growth is similarly sluggish, and inflation is slowing sharply as well (albeit from a higher starting point).

Our baseline is a series of 25bp cuts from the MPC starting in May that take Bank Rate back to 3% in 2025, but here too, the risks are tilted to the dovish side both in terms of the starting point and the speed of the adjustment.

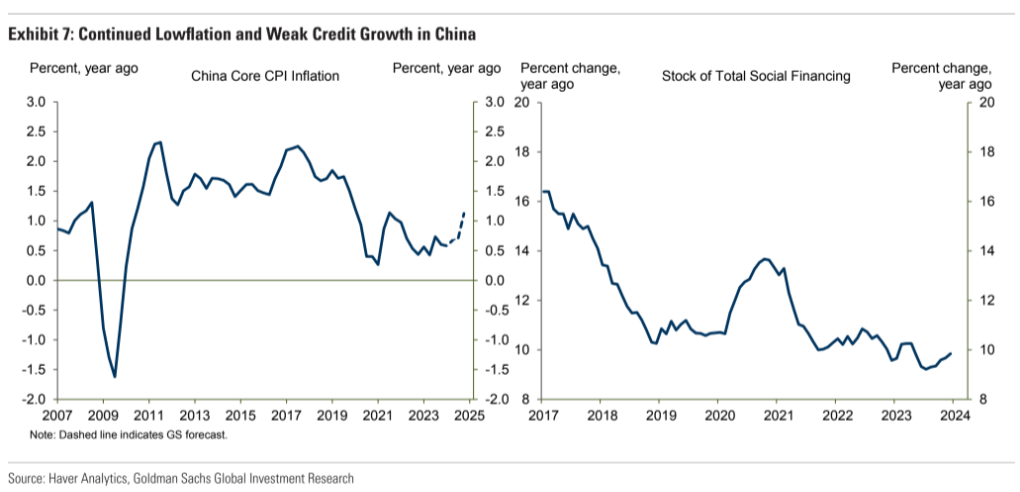

The case for macroeconomic easing is even stronger in China than in the advanced economies.

Core inflation remains stubbornly low, growth has failed to pick up decisively, and total social financing (i.e. credit) growth has failed to rebound despite a long series of incremental easing measures.

However, an aggressive turn toward stimulus looks unlikely and we expect more of the same from the PBOC—modest cuts in both interest rates and the reserve requirement ratio—as well as increased central government fiscal spending at a time when local governments are constrained by the need to deleverage.

But even such support probably won’t fully offset the headwinds from housing, debt, and demographics.

The likely result is deceleration in growth from 5.3% in 2023 to 4.8% in 2024, alongside continued lowflation.

Our economic forecasts should be friendly for risk asset markets, especially in the US where the move toward Fed easing is occurring alongside continued solid growth.

Accordingly, our equity and credit strategists have recently boosted their price and return forecasts.

With valuations high and recession fears currently lower among investors than among economists, however, we would reiterate the view of our cross-market strategists that the biggest opportunities will likely occur following periods when our optimistic forecast is under greater scrutiny than at present.

A few points:

- Slowing US credit tilts the base case to a weaker outcome and more cuts.

- Europe can and will cut.

- China is caught in a debt-deflation trap, and the failure to cut will entrench it.

Thanks to the fantastic mismanagement of the Albanese Government, Australia will not share in this bounty for borrowers as much. It has embedded energy and migration inflation so profoundly that it will take longer to deflate.

Still, I expect the RBA to be cutting by H2 and chasing global rates lower, not least because the Chinese depression will inevitably crash key commodity prices.

It is a constructive environment for risk assets thanks to expanding price multiples but not so constructive for earnings growth, meaning it will also be fragile and volatile.