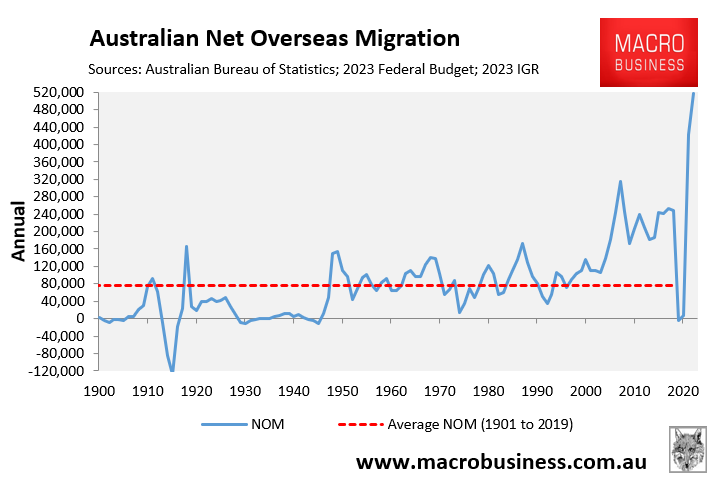

The primary cause of Australia’s current rental crisis is obvious: the record surge in the nation’s net overseas migration, which saw an unprecedented 518,000 net migrants land in 2022-23:

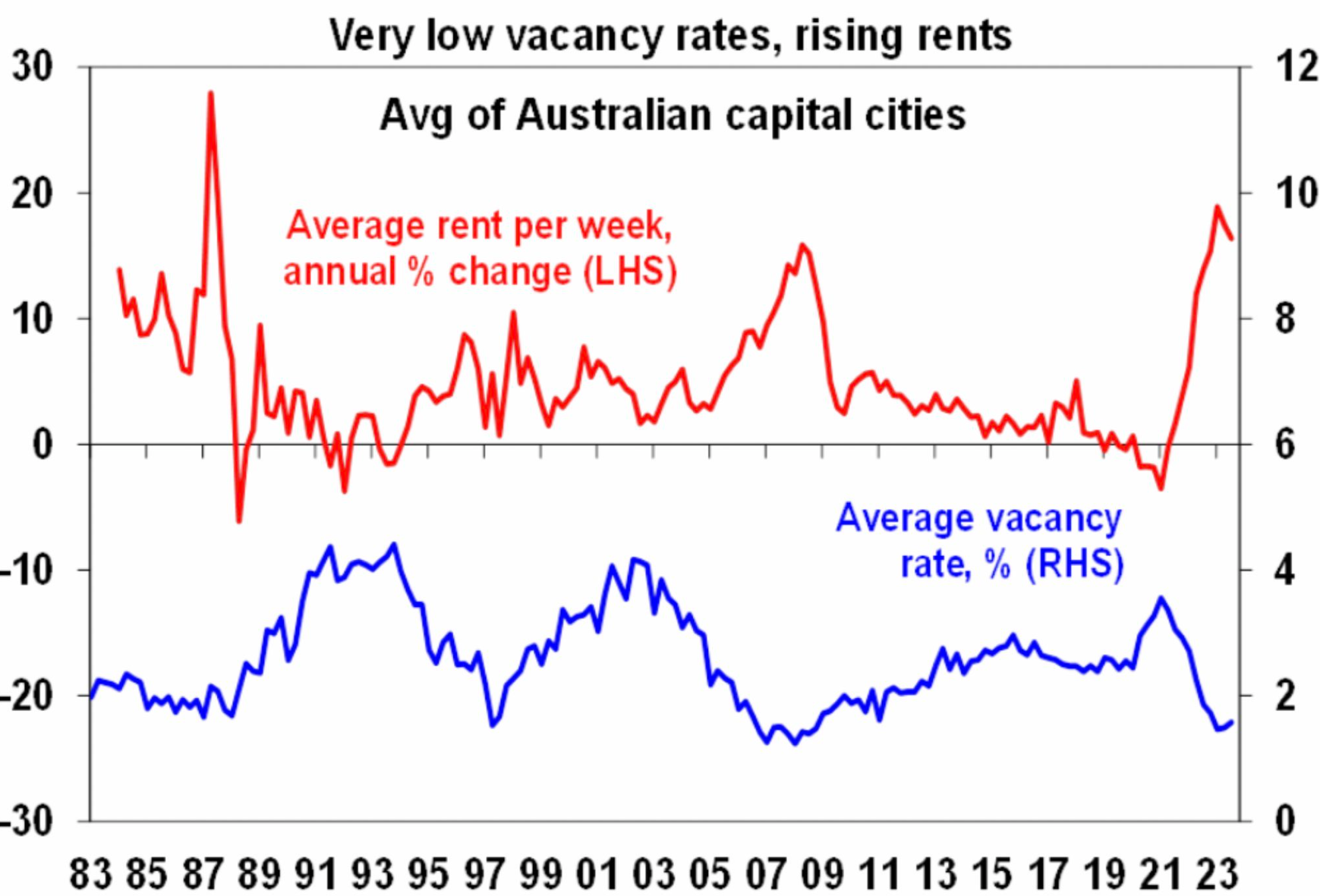

This surge in population demand has driven rental vacancy rates to historical lows, while driving rental prices to the moon.

Source: Shane Oliver (AMP)

Australia’s rental crisis is tipped to continue for the foreseeable future as historically high net overseas migration projected over coming years collides with falling rates of dwelling construction.

“Effective supply of housing is unlikely to catch up within the next three years”, because “we can’t build fast enough based on lack of materials and skilled labour, which makes it more expensive to build”, warned Associate professor J Ho from the School of Accounting, Economics and Finance at Curtin University earlier this month.

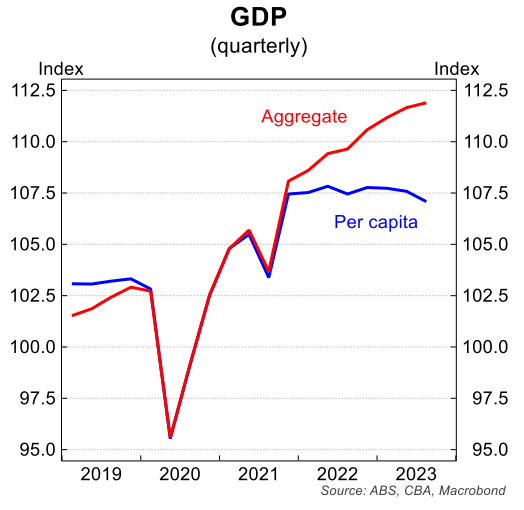

Meanwhile, per capita living standards are falling as Australia’s economy fails to grow sufficiently fast to soak up the historically high number of arrivals:

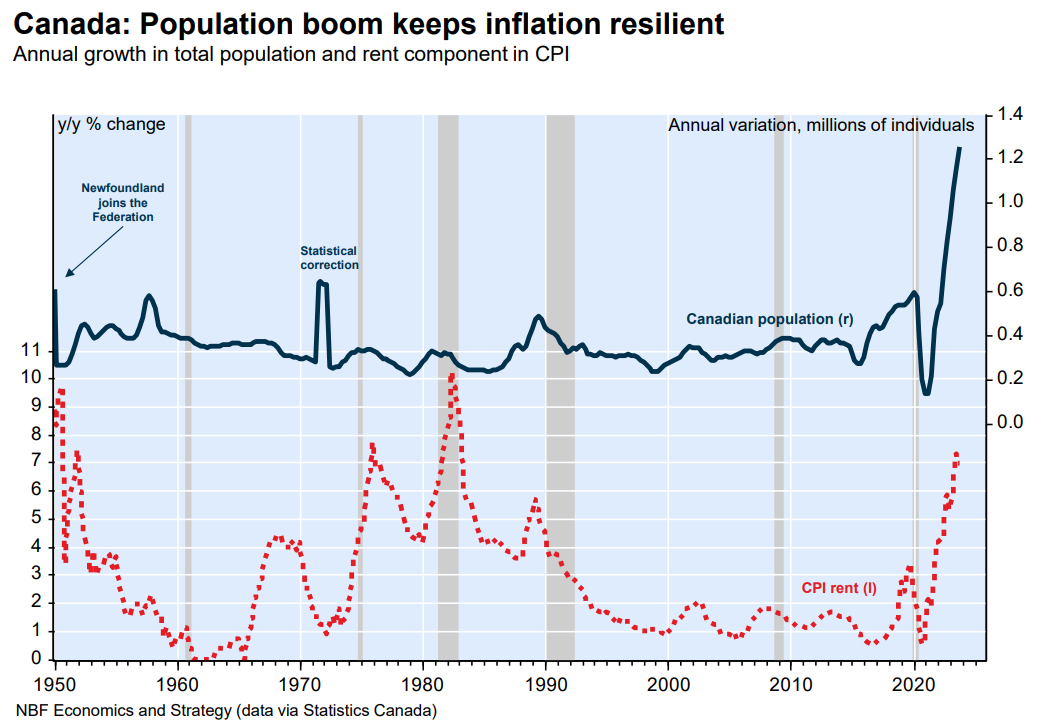

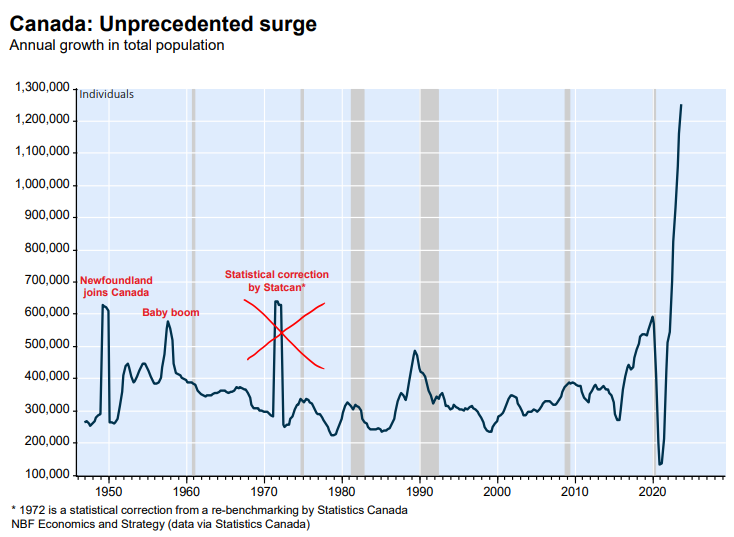

If you think the situation in Australia is bad, spare a thought for Canada, which has just experienced an explosive 1.2 million surge in population growth along with rampant rental inflation:

This has prompted National Bank of Canada authors, Stéfane Marion and Alexandra Ducharme, to warn that “Canada is caught in a population trap” whereby “no increase in living standards is possible, because the population is growing so fast that all available savings are needed to maintain the existing capital-labour ratio”:

“Canada’s population increased by more than 1.2 million in 2023, an incredible number given that it followed a rebound of 825,000 in 2022 after the Covid recession”.

“These are staggering numbers when you consider that prior to this, you would have to go back to 1949, when Newfoundland joined the federation, to see our country’s population increase by more than 600,000 in one year”.

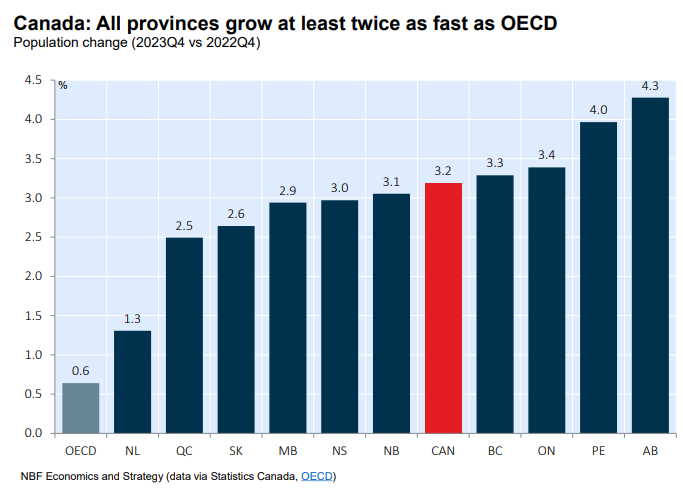

“To put things in perspective, Canada’s population growth in 2023 was 3.2%, five times higher than the OECD average. What’s more, all ten provinces grew at least twice as fast as the OECD, ranging from 1.3% in Newfoundland to 4.3% in Alberta”.

“Our country’s current population growth appears extreme relative to the absorptive capacity of the economy and the fact that our workforce is not aging faster than the OECD average”.

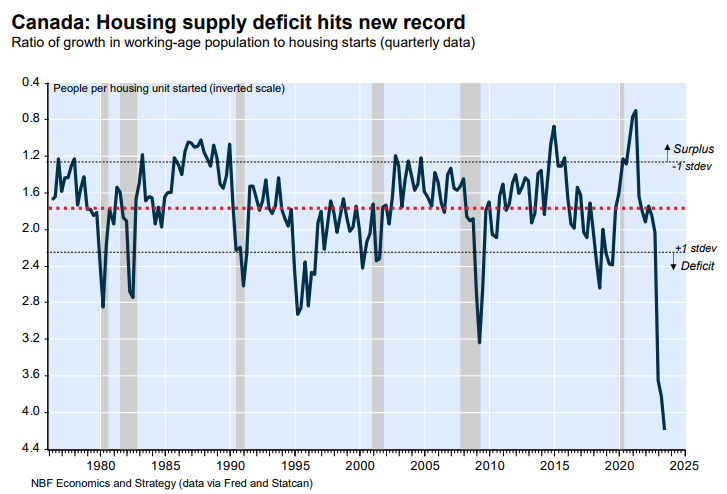

“Nowhere is this absorption challenge more evident than in housing, where the supply deficit reached a new record of only one housing starts for every 4.2 people entering the working-age population (compared to the historical average of 1.8)”.

“But to meet current demand and reduce shelter cost inflation, Canada would need to double its housing construction capacity to approximately 700,000 starts per year, an unattainable goal”.

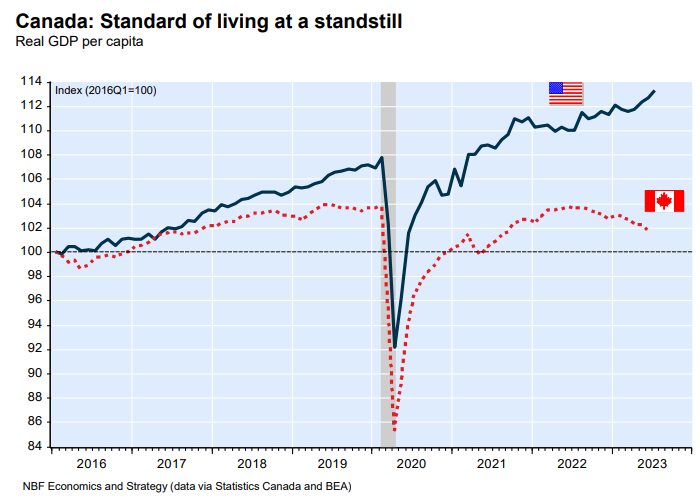

“In any case, our policymakers need to go beyond simply targeting housing supply and recognize that above a certain number, population growth is an impediment to our economic well-being. The fact that real GDP per capita has been at a standstill for six years is a case in point”.

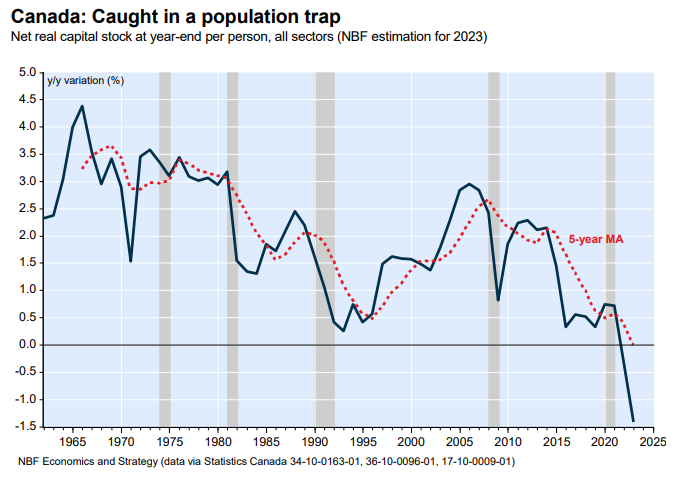

“Why is our productivity record so bad? Could it be that our demographic ambitions are too high relative to the stock of capital available in the country? According to our calculations, Canada’s capital stock per capita collapsed close to 1.5% in 2023”:

“This means that our population is growing so fast that we do not have enough savings to stabilize our capital-labour ratio and achieve an increase in GDP per capita”.

“Simply put, Canada is in a population trap for the first time in modern history. More worrisome is the fact that the decline is not simply due to a lack of housing infrastructure”.

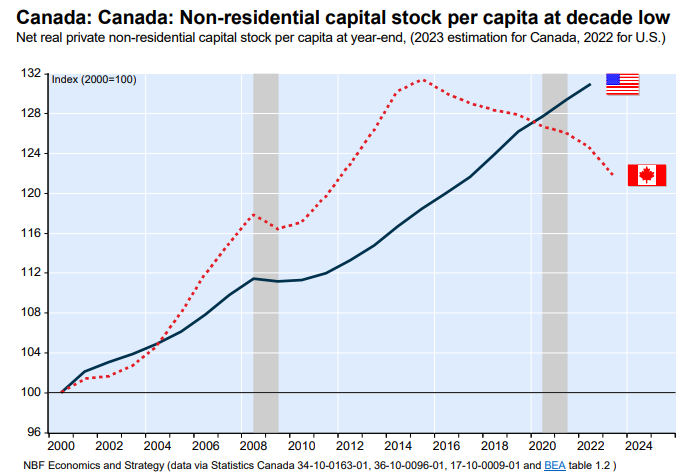

“In fact, the private non-residential capital stock to population ratio has been declining for seven years and is currently no higher than it was in 2012, while it is at a record high in the U.S”.

“Canada is caught in a population trap that has historically been the preserve of emerging economies. We currently lack the infrastructure and capital stock in this country to adequately absorb current population growth and improve our standard of living”.

“Our policymakers should set Canada’s population goals against the constraint of our capital stock, which goes beyond the supply of housing, if we are to improve our productivity”.

“At this point, we believe that our country’s annual total population growth should not exceed 300,000 to 500,000 if we are to escape the population trap”.

The above analysis is eerily similar to that of Gerard Minack’s with respect to Australia.

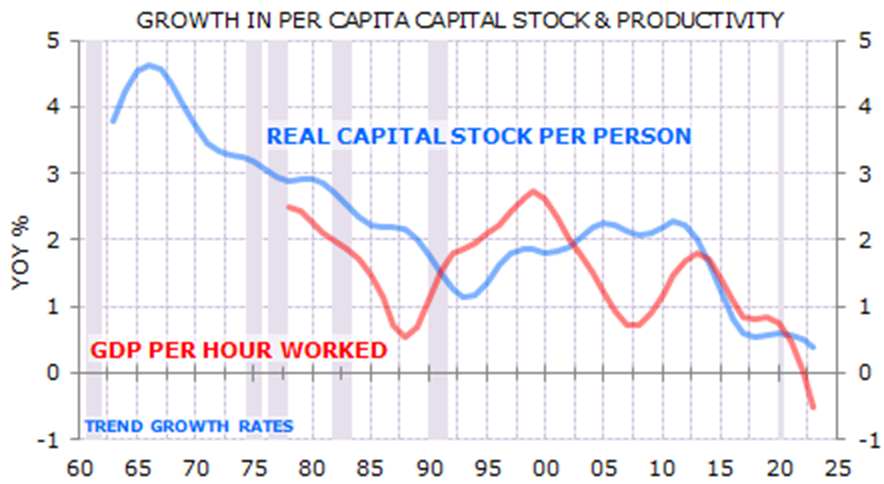

Minack likewise noted that capital stock per worker has shrunk, leading to “capital shallowing” and declining productivity:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”.

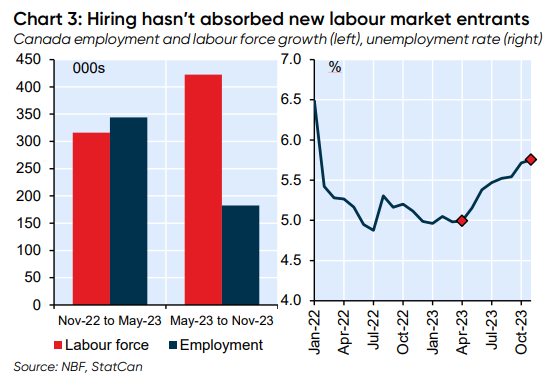

Separate National Bank of Canada analysis showed that, like Australia, Canada is failing to create enough jobs to soak up the record immigration-led labour supply growth:

“Given the record labour supply growth, a string of job-losing months isn’t even needed for more upward pressure on the unemployment rate”, the report reads.

For resource-rich nations like Australia and Canada, you literally could not devise a dumber growth model.

Importing millions of people necessarily spreads fixed mineral riches among more people, resulting in lower wealth per person (other things being equal).