The notion that international education is an “export” has been completely demolished this week with both industry players, commentators, and the government admitting that international education is really just a conduit for immigration (i.e. people imports).

On Monday, The Australian featured International Education Association of Australia CEO Phil Honeywood, who admitted that “the primary focus” of the international education system “is on students who can add skills to the Australian economy”.

On Tuesday, The SMH reported that the federal government will remove a rule that automatically blocks foreign students from getting a visa if they state that they wish to settle in Australia, in acknowledgment that international education is mostly an extension of immigration policy.

Immigration influencer, Abul Rizvi, supports the changes, noting that Australia was already providing pathways for international students to stay long-term.

“Why are we pretending otherwise?”, he said.

“I actually think the government should go further, and say one of the primary objectives of the international student program is to recruit future Australians because that’s what it does. Why not just say it?”.

The concept that international student graduates are filling critical skills gaps in the economy and significantly contributing to Australia’s talent base is incorrect.

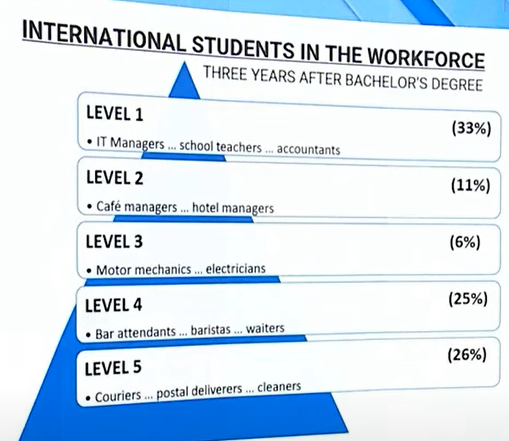

According to the graph below by Sky News’ Tom Connell, 51% of international student graduates with a bachelor’s degree who remain in Australia after three years work in low-skilled Level 4 or Level 5 jobs.

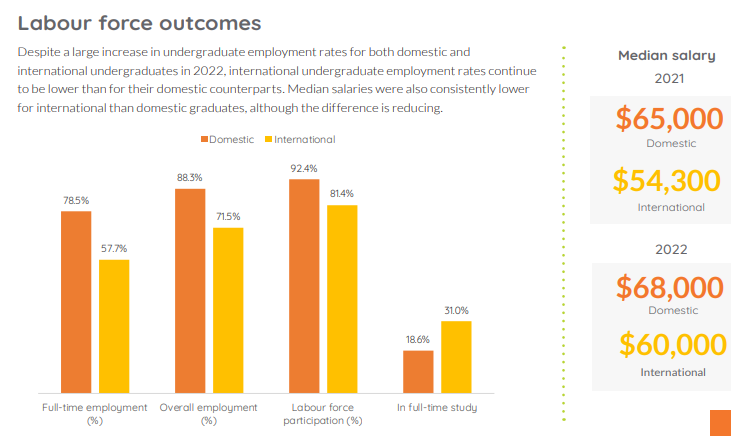

These findings are supported by the most recent Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS), which demonstrates that international graduates have much lower employment rates, participation rates, and median wages than domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

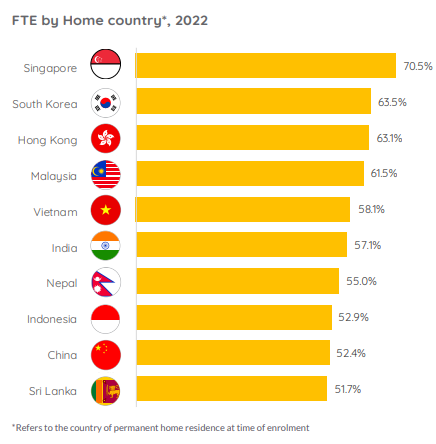

Worryingly, each of Australia’s three primary source countries for international students – China, India, and Nepal – has poor labour market outcomes in terms of full-time employment:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

It is no surprise that Australia is suffering widespread skills shortages if this is what the international education industry is producing in record numbers.

Australia’s international education Ponzi scheme has created a large underclass of low-wage, low-skilled migrant workers.

Instead of continuing the farce and enticing large volumes of sub-par students to Australia, policymakers should instead focus on attracting a small pool of excellent (genuine) students by significantly raising financial barriers to entry as well as entrance requirements (particularly for English language proficiency), and removing the clear link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

International education should be all about quality over quantity, and excellence over volume.

Otherwise, Australia will repeat the same mistakes of the past decade with rampant youth unemployment, wage theft, exploitation and crush-loaded housing and infrastructure becoming endemic, alongside a growing migrant underclass.