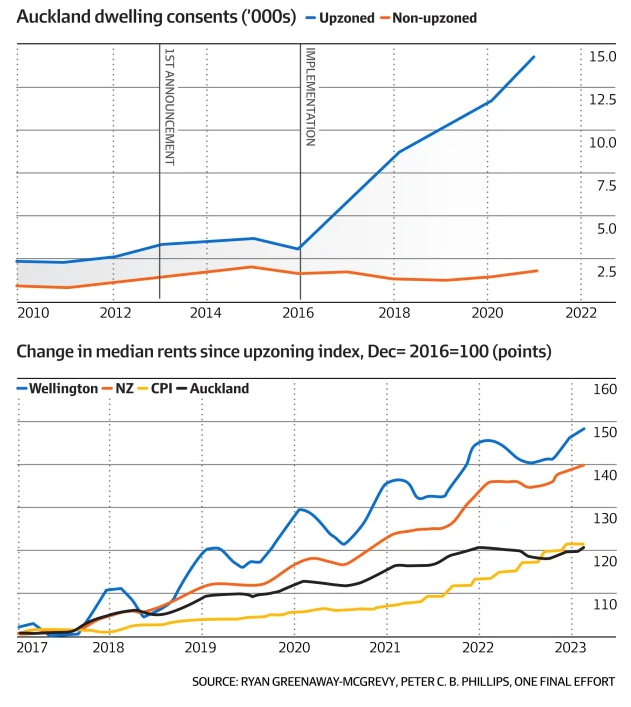

The media in Australia and across the world were enamoured last year with research claiming that ‘upzoning’ planning reforms implemented in Auckland in 2016 had a significant impact on lowering house costs.

Under the reforms, roughly three-quarters of residential land across Auckland was upzoned, which the ‘research’ claimed resulted in tens of thousands of additional new homes being built over the following five years.

The media, the property lobby, and the YIMBY movement all leapt on the study’s results, demanding that Australia adopt upzoning regulations similar to those in Auckland to solve the rental crisis.

This viewpoint was encapsulated by Michael Read’s article last year in The Australian Financial Review:

“A radical move in 2016 to liberalise zoning laws in New Zealand’s largest city ushered in a building boom that has spared the region from the big increase in house prices and rents across the rest of the country”, argued Read.

“It could also be a blueprint for Australia, where restrictive planning laws have been blamed for a shortage of rental accommodation and high house prices”.

“Overall, about 75% of Auckland’s residential land was upzoned as a result of the plan, tripling the city’s dwelling capacity”.

“The increase in supply has kept a lid on rents and house prices”.

PropTrack senior economist, Angus Moore, touted the Auckland study on Thursday, arguing that relaxing “planning” could reamp-up construction activity and ease Australia’s housing crisis:

“The experience in Auckland, which undertook similar [planning] changes in 2016, shows that it could ramp up housing construction activity and improve affordability,” Mr Moore said.

“A study by Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips compares areas affected by the upzoning with areas that weren’t, and finds a substantial increase in construction in affected areas,” Mr Moore said.

“They estimate that the upzoning led to an additional 21,000 new homes above and beyond the normal pace of building between 2016 and 2021.”

I questioned the study’s validity at the time, arguing that it used a “biased sample”. Dr Cameron Murray did the same on his Fresh Economic Thinking website (see here and here).

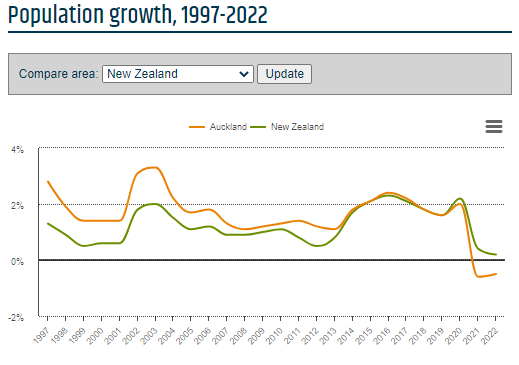

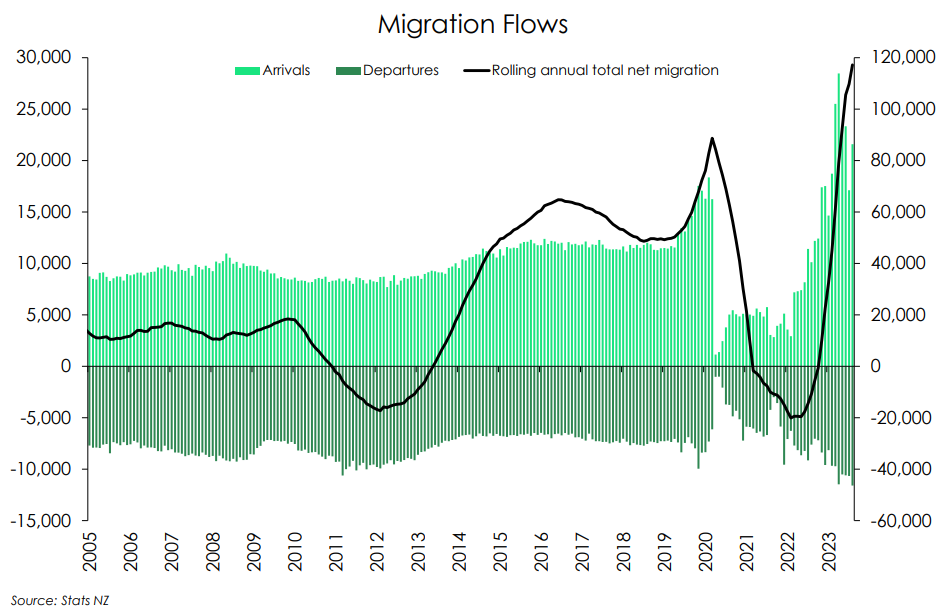

The paper also conveniently omitted the fact that many New Zealanders fled to other cities in response to the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns. In turn, population and rents in Auckland fell:

New Zealand’s population growth has since rebounded hard due to record net overseas migration:

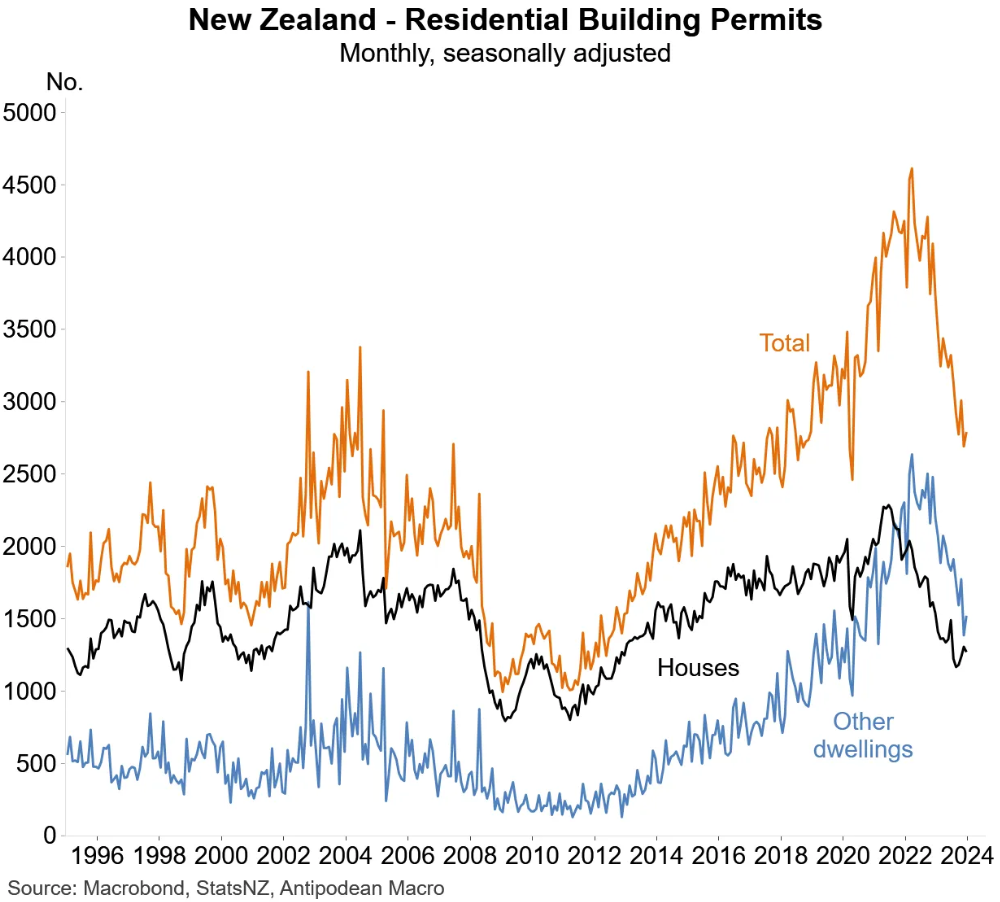

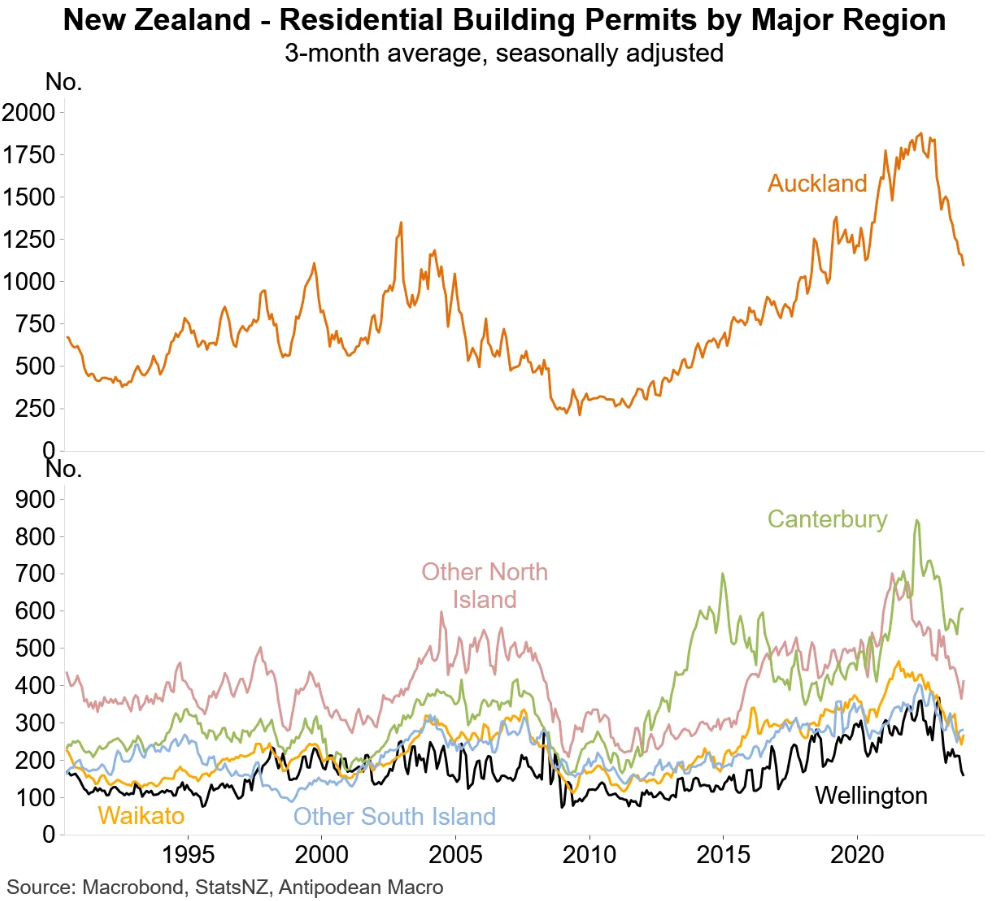

Much like Australia, dwelling construction is also crashing due to high interest rates, elevated materials costs, and labour shortages (chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro):

Auckland is also leading the decline in residential building permits:

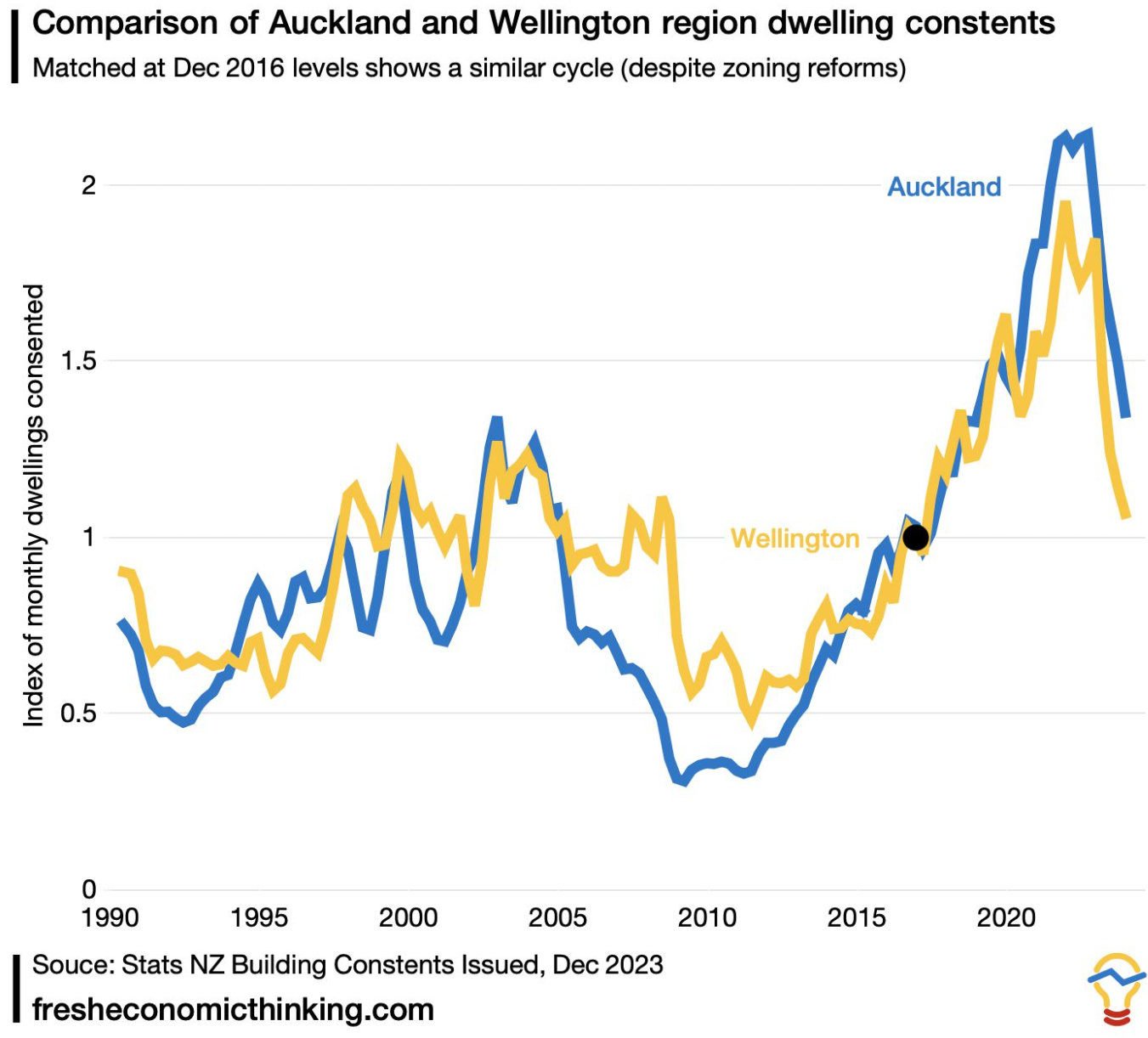

Hilariously, the above study made a point of comparing upzoned Auckland against Wellington, which was considered a “cartel to restrict housing”.

Yet, as the below chart from Dr Cameron Murray shows, there is minimal difference in both cities’ construction profiles:

Large volumes of migrants have landed in Auckland, which has prompted concerns that the city is facing another rental crisis:

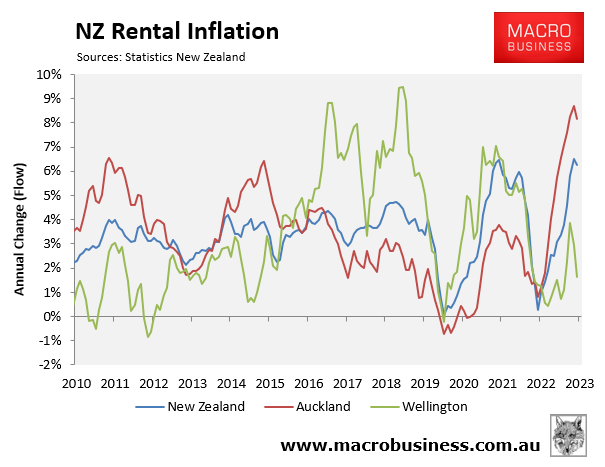

The strong rebound in Auckland’s population growth is driving rents, just as it did when Auckland’s population growth fell sharply over the pandemic:

As you can see above, Auckland rents are now growing much faster than Wellington’s and the national average.

So much for Auckland’s much-lauded planning reforms.

Strong immigration into Auckland is fueling the city’s rapid rental inflation, just as negative migration in previous years held rents down.

Who would have thought?