IFM Investors chief economist Alex Joiner has penned an article at LiveWire Markets questioning whether the next rate-cutting cycle from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will actually ‘help’ the economy this time around:

“The expectation is that the RBA to cuts rates as it has always done and economists will model the same outcomes. Whilst at the same time risk ignoring recent pre-pandemic history that highlighted that lower and lower rates assist at the margin but are not the solution to many of the economy’s problems and indeed may exacerbate them”.

“The rationale for lowering rates is simple and largely unchallenged: support the economy as much as possible, while maintaining inflation within the target band. As are the key tenets of the lower interest rate playbook – disincentivize savings, free up borrower cash flow, push up asset prices and make borrowing more attractive”.

“But does this still hold? And are these the outcomes we want?”..

“It is well known that lower rates historically lead to asset prices rising in excess of income growth, higher dwelling prices, more household debt, undermining affordability and exacerbating inequality. This will threaten to again be the case again in the coming easing phase. But do we need that when we already have one of most indebted household sectors globally and so many locked out of homeownership due to affordability issues?”

“Many would argue these effects are important growth drivers needed to support spending and kickstart the dwelling construction cycle. But equally we have experienced how price booms invariably see first home buyers crowded out of the market. And how high debt levels impact households negatively both economically and socially over the medium term”…

“The decade preceding the pandemic was one of lower and lower rates, but few would argue this made the economy better, more robust, or more equitable. Indeed, economic growth during this period could best be described as anaemic”…

Joiner raises some pertinent points.

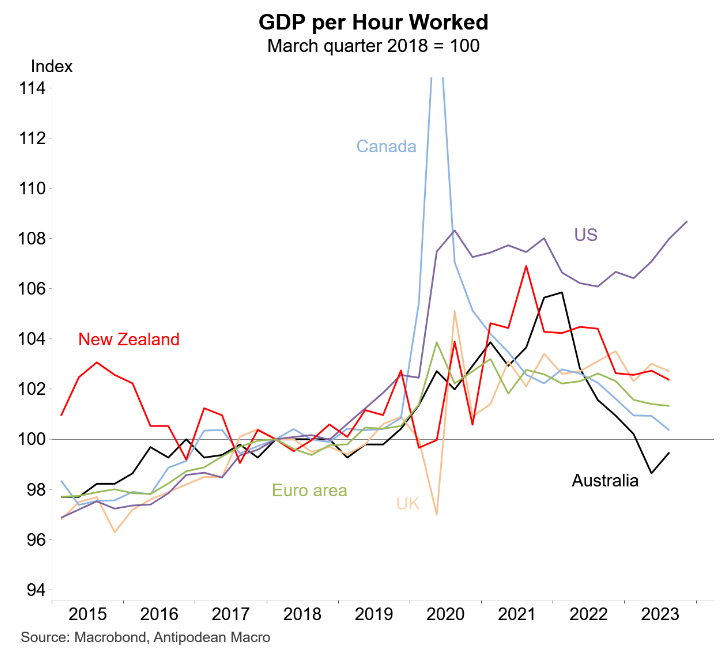

The last rate-cutting cycle certainly did not help to improve Australia’s productivity, which is atrocious and tracking at 2016 levels:

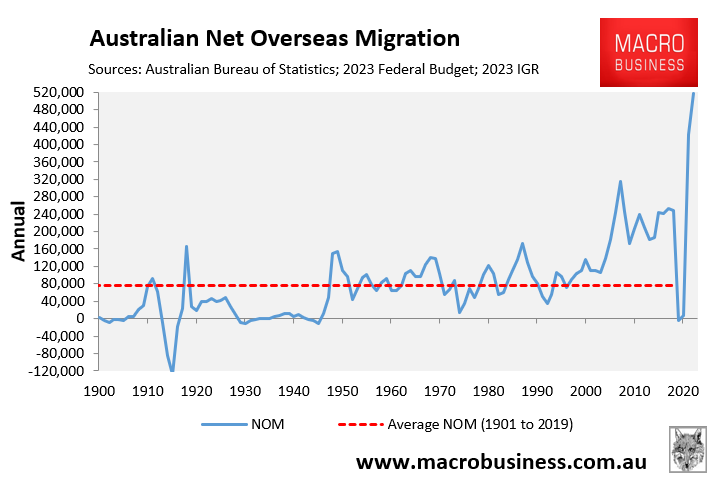

In fact, Australia’s productivity growth only grew when immigration was cut over the pandemic, only to then crater when immigration rebounded strongly (a similar situation has occurred in Canada, as shown above).

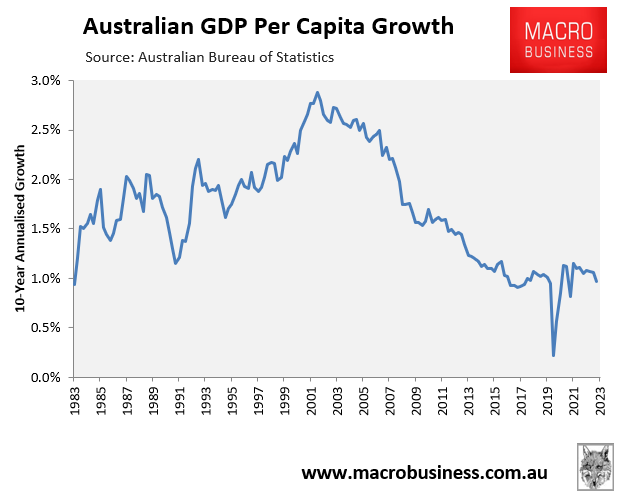

Australia’s per capita GDP growth has also cratered:

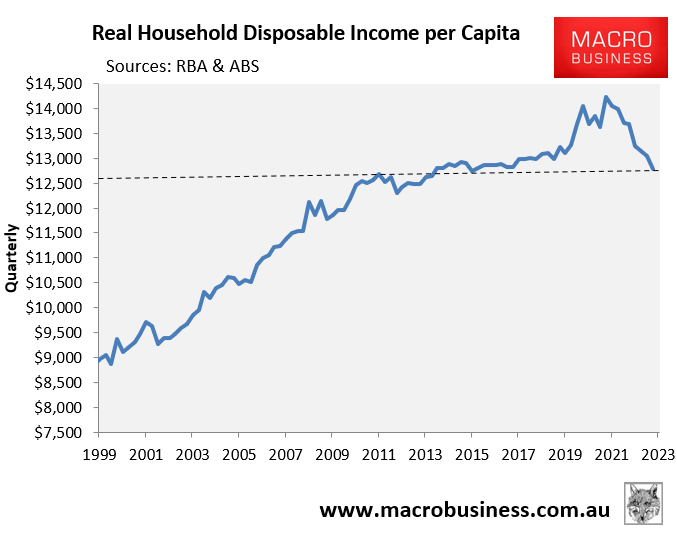

Household disposable income per capita has also fallen to around 2012 levels:

The key problem is that the RBA has only one instrument – interest rates – to stimulate/dampen the economy. And it will lower interest rates in a bid to juice growth.

But ultimately, interest rates cannot overcome the deficiencies of government policies and the broken economic structure.

Idiotic government policy has delivered Australia an unnecessary energy shock, with Australians on the east coast paying global prices, despite being a super power in gas and coal.

Idiotic federal government policy has also destroyed productivity and living standards by running an extreme immigration policy, which has delivered “capital shallowing” because business investment, housing and infrastructure cannot keep up.

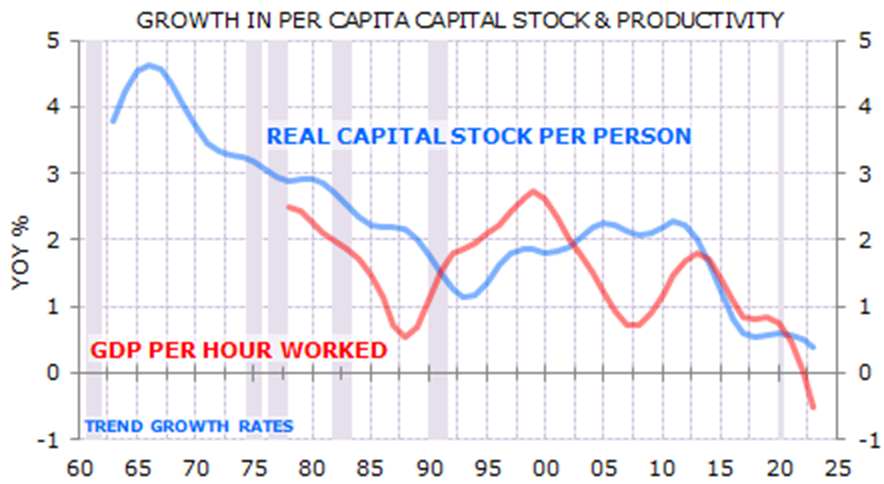

This “capital shallowing” was stunningly illustrated in the below chart by independent economist Gerard Minack in his November report:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, Minack wrote.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, Minack warned.

Large-scale immigration also diverts resources, encouraging the creation of low-productivity “people-servicing” businesses while directing the nation’s productive effort towards infrastructure and housing.

Australia is also unique in that it pays its way in the world mostly through the sale of its fixed mineral reserves.

Importing a huge number of people through immigration distributes these mineral riches among more individuals, resulting in reduced wealth per person.

Interest rates only impact the economy in a cyclical sense, whereas Australia’s economic troubles are structural.