The RBA minutes yesterday were another crack smoking laugh out loud affair. There was some acknowledgement of recent economic weakness:

Members observed that inflation in Australia had moderated, with both headline and underlying inflation lower in the December quarter 2023 than had been expected three months prior. Core goods price inflation had declined faster than expected, as also seen abroad. Services price inflation, which largely reflects conditions in the domestic economy, had declined to a lesser extent and remained high.

Members discussed how much signal to take from the faster-than-expected decline in inflation in the December quarter and whether goods price inflation might fall further given ongoing excess capacity in the Chinese economy. They also considered the implications for inflation if various subsidies that were due to expire were extended.

Members discussed how high inflation, higher taxes and tighter monetary policy had contributed to a noticeable slowing in growth in aggregate demand over 2023. Looking through the volatility in monthly outcomes, retail sales volumes were expected to have been broadly unchanged in the December quarter.

Retailers had reported that similar conditions had persisted into the first part of 2024. More broadly, weak household spending growth, particularly in per capita terms, had been only partly offset by strong growth in business investment and public demand.

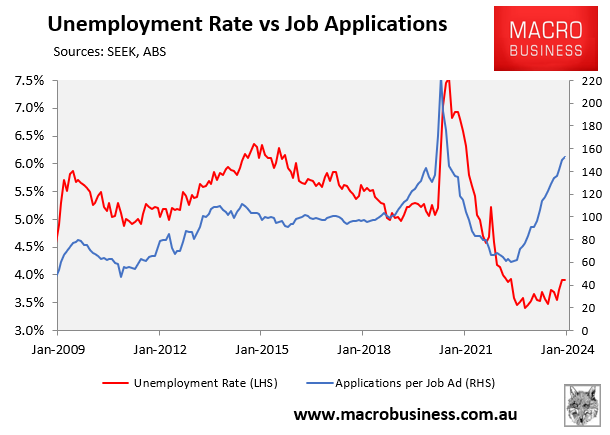

Labour market conditions had remained tight but had continued to ease over preceding months in response to slower economic growth. The unemployment rate and underemployment rate had both increased by around ½ percentage point since mid-2023, albeit from low levels.

Overall, conditions in the labour market were assessed to be tight relative to what would be consistent with sustained full employment

However, the bank is still stuck analysing the economy without a single refernce to the one major input that distorts the relationhisp between capacity, wages, inflation and producivity: immigration.

Members noted that consumption growth had remained subdued and was a little weaker than previously expected. The slowing in consumer spending reflected the impact on growth in real household disposable income of high inflation and a higher tax and interest burden.

Real household disposable income was expected to grow in the period ahead, including because of the anticipated decline in inflation. Despite subdued consumption growth, overall growth in GDP remained modest, supported by a number of other parts of the economy that had been growing strongly.

While overall growth had been modest, members agreed that aggregate demand was still high relative to the economy’s supply potential, which was generating inflationary pressures.

Members acknowledged the significant uncertainties around the economic outlook. The most material risks were the potential for inflation to be more persistent than anticipated, productivity growth not to recover as assumed and consumption to weaken more markedly than in the staff’s central forecast.

Members noted that the staff’s central forecasts were for inflation to return to the target range of 2–3 per cent in 2025 and to the midpoint in 2026, with the unemployment rate rising modestly as growth in labour supply outpaces growth in employment.

This was predicated, however, on inflation expectations remaining anchored around the midpoint of the target range and some assumed recovery in productivity.

Members considered the policy implications of a scenario in which inflation expectations instead gradually drift up and another where consumption is materially weaker than in the central forecasts.

The case to raise the cash rate further centred on the observation that it would take some time for inflation to return to target and the labour market to full employment.

Inflation was expected to take a further two years or so to return towards the midpoint of the target range under the central forecast. This was consistent with the staff’s assessment that aggregate demand remains above the economy’s supply potential.

Members noted that an increase in the cash rate target at this meeting could slow the growth of demand further and reduce the risk of inflation not returning to target in an acceptable timeframe.

Increasing the cash rate target now would not prevent the Board from easing monetary policy if the economy were to weaken more sharply than envisaged.

The case to leave the cash rate target unchanged at this meeting centred on the observation that the risk of inflation not returning to the Board’s target within a reasonable timeframe had eased.

The moderation in inflation over preceding months had been slightly larger than previously expected, and global inflation outcomes had provided additional confidence that inflation in Australia would moderate further.

Data on the labour market and consumer spending had also been weaker than previously expected.

Members noted that it was possible that conditions in the labour market were already consistent with full employment, although this was judged to be unlikely.

And there it is. It’s not only likely that we’re at sustainable full employment. It is probable that we are loosening into excess as we speak:

We should accept that a certain amount of labour mismatching is going on owing to Albo’s low quality Indian army but the RBA still isn’t taking into consideration the effects of booming immigration labour supply, which is why it was wrong, and overly tight, the entire previous business cycle.

Now it’s doing it again and once again will overshoot the unemployment and underemployment numbers such that wages, growth, inflation and living standards all slump into another lost decade.

Labor slack has already moved materially past the RBA’s latest outlook and it will force a panicked rates reversal in due course.