The Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) has published an interesting report explaining how New Zealand has solved its labour shortage by engaging seniors in the labour force.

IPA noted that “Australian pensioners and veterans face an effective marginal tax rate of 69% if they choose to work”, which is a major disincentive.

By contrast, “pensioners and veterans in New Zealand can earn income without their entitlements being clawed back, meaning their total tax rate is as low as 10.5%”.

“One in four New Zealand pensioners work, compared to only 3% of pensioners in Australia”, notes the IPA.

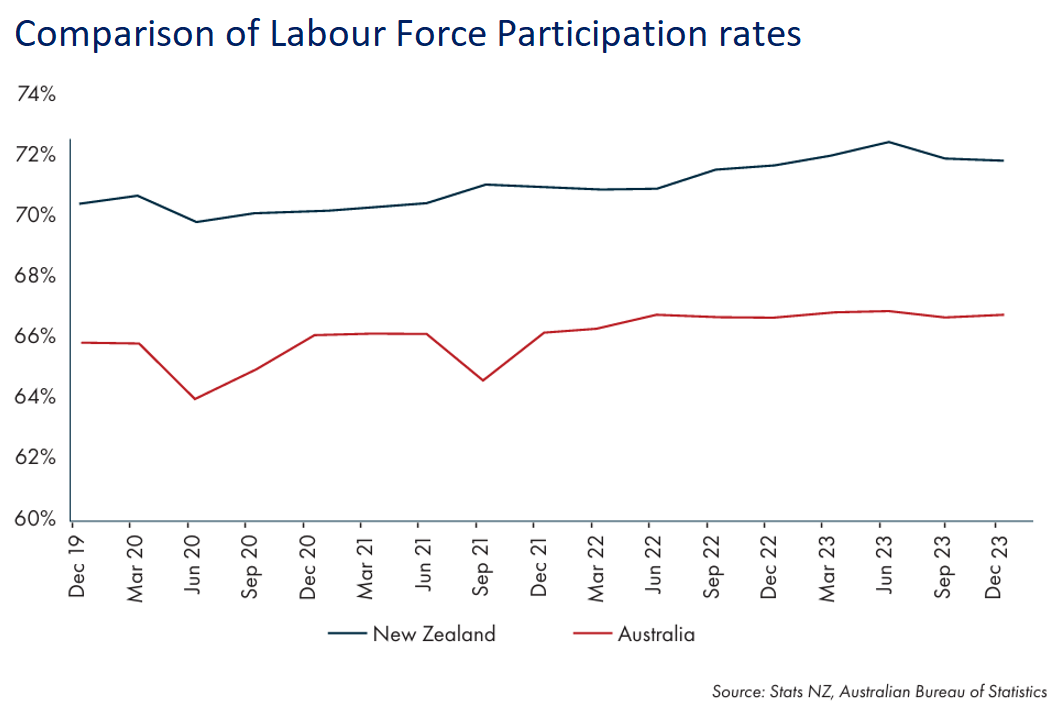

As a result, New Zealand enjoys far higher labour force participation rates than Australia:

“90% of the difference between Australia and New Zealand’s labour force participation rate is attributable to the gap in pensioner participation”, according to the IPA.

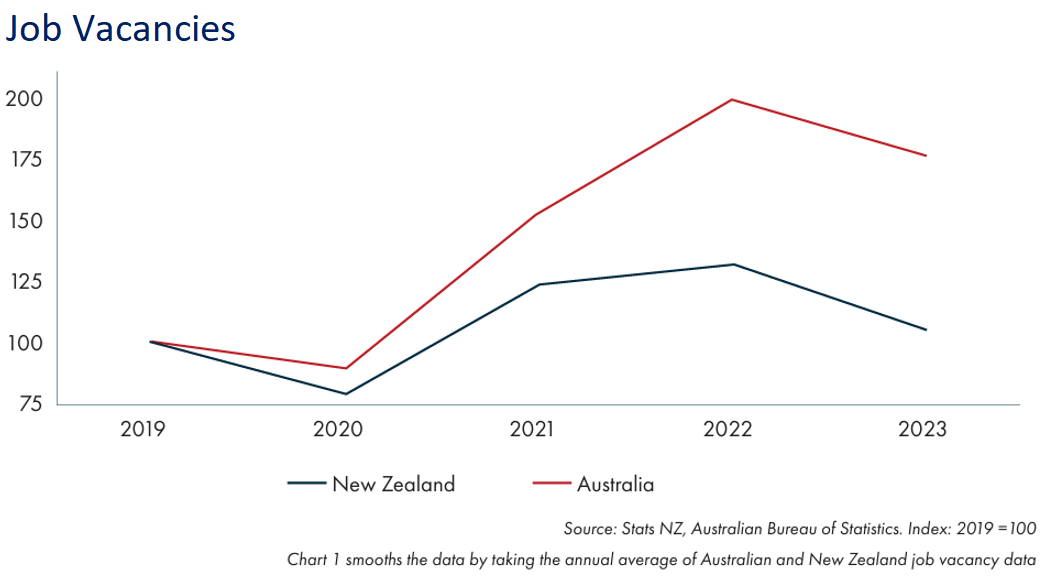

This higher participation from seniors has helped New Zealand plug labour shortages, with vacancies in New Zealand only 5.4% above its 2019 level, versus 77% above 2019 levels in Australia:

IPA concludes by arguing that “adopting the New Zealand pension model could result in up to 520,000 more Australians participating in the labour force, far more than the 388,000 job vacancies currently in the economy”.

The reason New Zealand’s labour force participation rate is so much higher is because the aged pension is not means tested and is available to anyone.

As a result, pension-aged Kiwis who want to work more do not lose their pension; instead, they pay tax on their additional earnings.

Two other top pension systems, the Netherlands and Denmark, have defined benefit programs, or universal basic pensions, in place and have significantly higher labour force participation than Australia.

National Seniors Australia (NSA) chief, Ian Henschke, has previously noted that pensioner labour force participation in the United States (20%), Israel (21%), and Sweden (20%) is also far superior to Australia’s (3%) rate.

In addition to the labour force participation benefits, a universal-style pension would reduce complexity and administrative expenses by eliminating the need for means tests, taper rates, deeming rates, and so on.

A universal pension would also abolish the game-playing and manipulation that older residents engage in in order to maximise their Age Pension benefits.

Instead of constantly importing hundreds of thousands of migrants into Australia in a bid to ‘solve’ labour shortages, which puts undue strain on infrastructure, housing, and the environment, why not make better use of pensioners who want to work but are unable to do so due to punitive pension rules?

Australia should simply copy New Zealand on this issue.