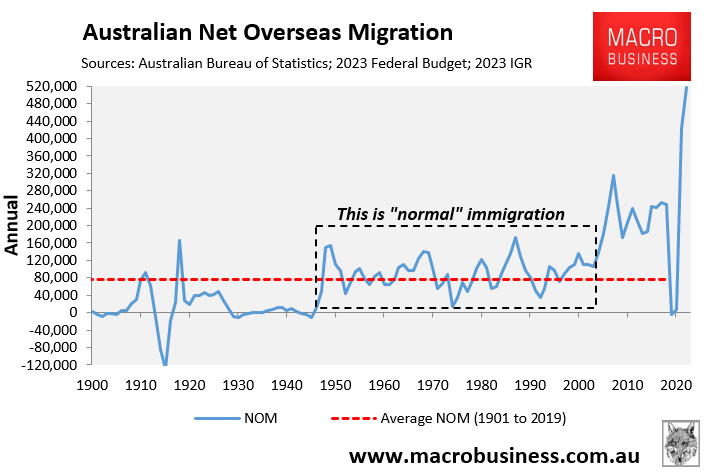

Over the past week, we have witnessed widespread discussion on the deleterious impact that Australia’s record immigration is having on the rental market.

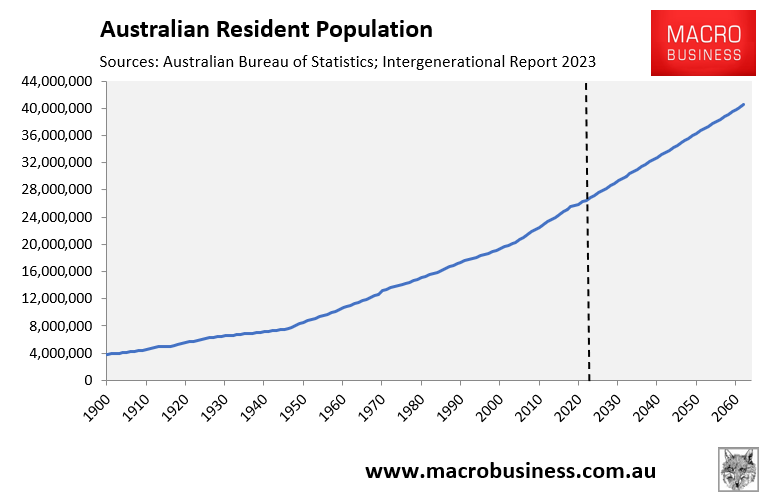

Today, I want to discuss a longer-term problem that Australia faces as its population swells to a projected 40.5 million people by 2063: water supplies.

Australia is one of the driest nations on earth and is facing chronic water shortages as its population grows by a combined Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane in only 39 years.

Most of this growth will occur along the east coast in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, and will overwhelm existing water supplies.

For example, Warragamba Dam supplies around 80% of Sydney’s drinking water. But that was built in 1960 when Sydney’s population was just over 2 million people.

Today, Sydney’s population is approaching 5.4 million people and is projected to grow to around 9 million people by 2060.

Anybody possessing even a sliver of common sense should see the problem here, especially when natural sources of water are projected to become less reliable in the future due to climate change and increased evapotranspiration rates.

“The predictions are the climate is going to provide us less rain and the population keeps going up, supply is going down”, warned Ian Wright, an associate professor in environmental science at Western Sydney University.

“If we look at a long-term sustainable yield we believe that demand is already exceeding that long-term sustainable yield”, Professor Stuart Khan, the head of civil engineering at the University of Sydney, added.

Infrastructure Australia (IA) has released several reports warning of future water shortages and rising costs.

In its 2017 Report entitled “Reforming Urban Water: A national pathway for change”, IA modelled that household water bills would increase by around four-fold in real terms as expensive technological solutions, such as desalination, supplant traditional dam water as the main sources of urban water supply:

IA’s 2019 Infrastructure Audit warned that “climate change, population growth, ageing assets, and competing interests will ramp up pressure for limited resources”.

“The water sector relies heavily on rainfall to replenish storages, streams and groundwater, and on vibrant ecosystems to support a reliable water cycle. Higher temperatures can also increase the volume of water in storage lost through evapotranspiration”.

“Population growth is ramping up pressure on limited water supplies… Water planning on the basis of long-term population growth projections is problematic, with the growth of our major cities consistently underestimated”.

“The combined impacts of climate change, population growth, rising community expectations and ageing networks mean that costs of providing services are likely to put upward pressure on household budgets over coming years”.

A 2020 report from the Productivity Commission (PC) also warned that “major supply augmentations will be needed to meet increasing demand”.

“Scenarios developed for Melbourne, for example, include a worst case of demand outstripping supply by about 2028 without further supply augmentation”.

“Looking ahead, climate change and population growth present significant risks to the security of Australia’s water resources”.

“Drought conditions are likely to become more frequent, severe and prolonged in some regions. Higher anticipated demand from a growing population, alongside reductions in supply, will increase water scarcity and put further pressure on all users (including the environment)”.

Given the expected reduction in precipitation due to climate change, as well as the long-term water scarcity that Australia will face, why is the federal government running a mass immigration policy on the world’s driest continent?

Only five years ago, Australia experienced a catastrophic drought that reduced water supplies to dangerously low levels.

What will happen the next time Australia faces a severe drought and needs to provide water and food to millions more people?

To accommodate the projected 14 million additional people by 2063, Australia will need to construct a battery of costly, energy-intensive, and environmentally damaging water desalination plants.

Water desalination is significantly more expensive than traditional water sources, which will result in higher water costs, as shown by IA above.

Furthermore, distributing desalinated water to inland areas like Western Sydney is intrinsically difficult and costly since water must be transported uphill over long distances.

As a result, residential and commercial water prices would skyrocket to support the federal government’s mass immigration agenda, which will disproportionately harm lower-income households.

Water is another illustration of how the federal government’s ‘Big Australia’ immigration program hurts the environment and lowers Australian living standards.

Simply reducing net overseas migration to historical levels of less than 120,000 a year would better protect the nation’s water supplies at a reduced cost to end users.

The federal government’s ‘Big Australia’ mass immigration policy is the most serious threat to Australia’s water supply.

Lowering immigration to sensible and sustainable levels is, therefore, the number one solution.