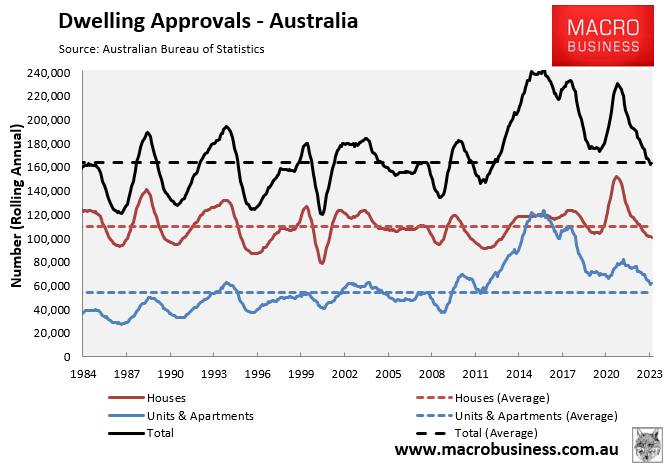

The Albanese government’s 1.2 million housing target comes into effect from 1 July. It requires 240,000 homes to be built annually for five straight years, or 20,000 new homes per month.

The latest dwelling approvals data shows just how delusional this target is, with only 163,000 homes approved for construction in the year to January 2023, 77,000 below the government’s target:

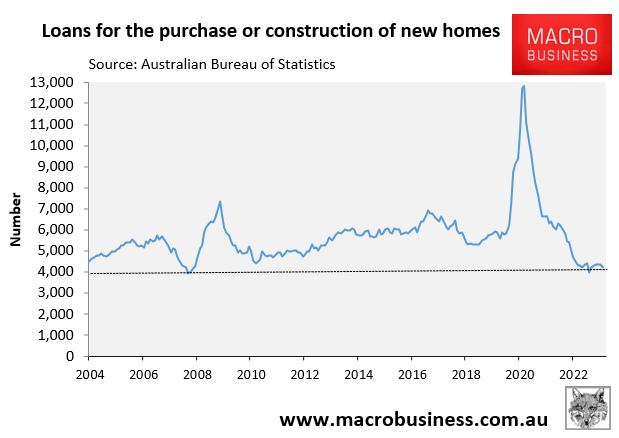

Loans for the purchase and construction of new homes also fell to historical lows in January:

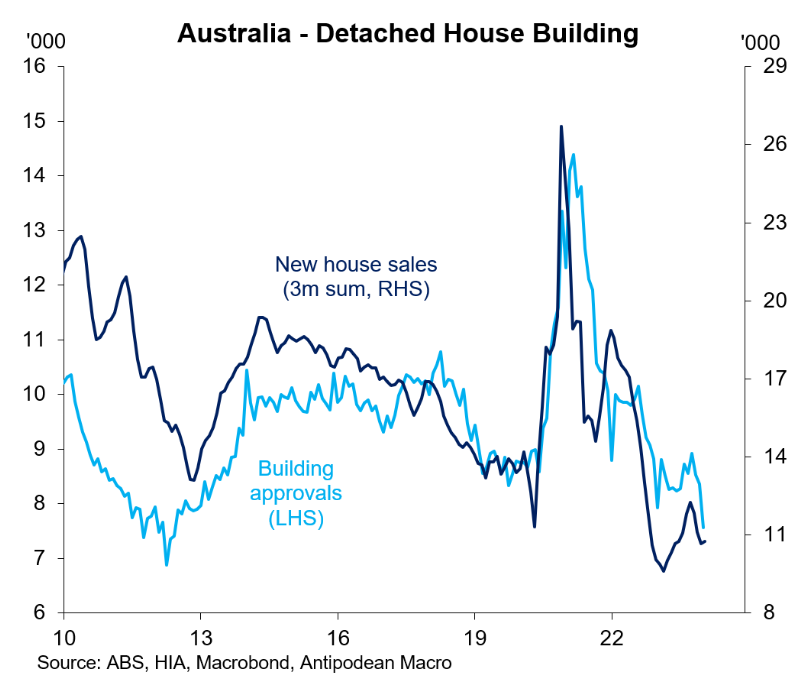

Last week, the Housing Industry Association (HIA) released new home sales data, which showed that sales remain weak.

The next chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro plots quarterly new home sales against building approvals, with both falling:

Commenting on the results, HIA Chief Economist, Tim Reardon, noted that “the slowing in sales and building approvals will flow through to a decade low volume of new houses commencing construction in 2024”.

“The economic impact of this slowdown will become increasingly evident in 2024, as employment in the home building industry falls”.

“The higher borrowing costs are compounding the elevated cost of land and construction, drying up the pipeline of new home building work despite the significant pent-up demand for housing”, Reardon said.

Professor Nicole Gurran, an urban planning researcher and policy analyst at the University of Sydney, seems sceptical that the Albanese government’s housing target can be met.

She told 9news that the lack of new projects is due to the combination of high interest rates, supply chain bottlenecks, and worker shortages pushing up material and labour costs.

“I don’t think anyone’s surprised at all to see that projects aren’t coming forward for approval”, she said.

“They’re certainly not being completed either – you’ve got quite a lot of approvals already in the system that developers aren’t acting on because it’s risky”.

Meanwhile, The New Daily reports that more than 80 groups have called on the Albanese government to fix the housing crisis:

The coalition group has written to Federal Housing Minister Julie Collins demanding action on youth homelessness, in particular.

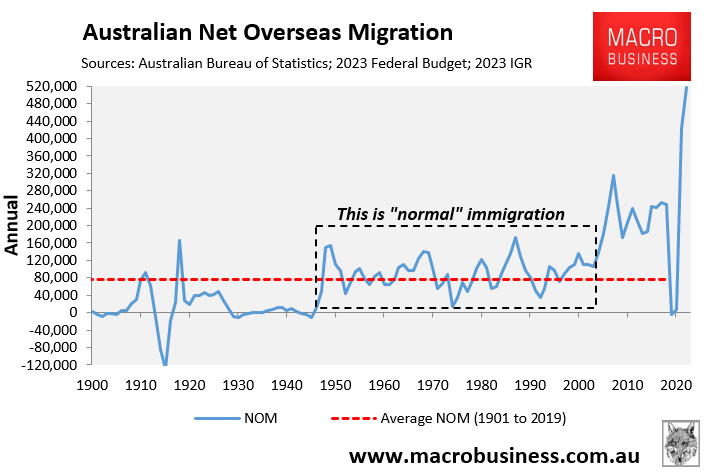

The fastest and first best solution to the housing the housing crisis is to simply lower net overseas migration from its current absurd level to around historical levels of less than 120,000 net migrants a year:

This solution could be achieved quickly, at low cost, and would also take much-needed pressure of infrastructure and natural environment.

Sadly, we have people like Maiy Azize standing in the way of sensible immigration policy, gaslighting with the following:

“It is nonsense to blame overseas migration as a primary driver of a housing crisis that has been decades in the making”, Azize said.

“During the Covid era which had lower migration, rents actually increased more than they did in the preceding decade”.

It’s strange that Azize should make such a claim when net overseas migration was ramped up from 2005 – i.e. decades ago – thus being an integral cause of the problem.

Furthermore, Azize’s claims surrounding rental growth are delusional.

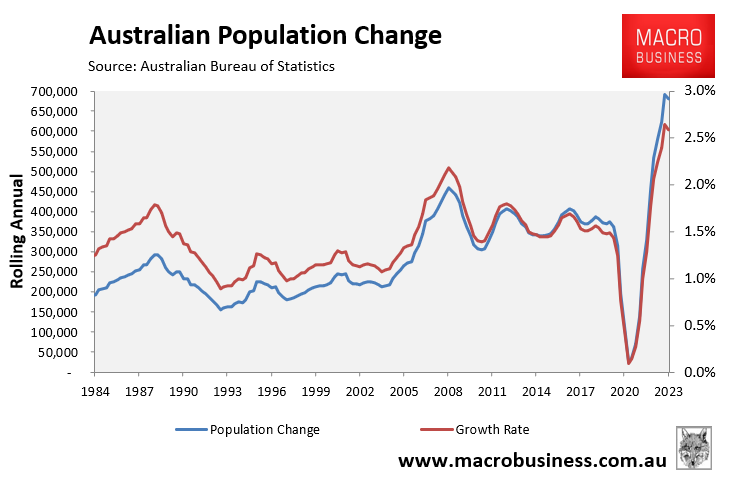

Population growth slowed to a crawl during the pandemic when net overseas migration briefly turned negative before exploding to current record levels of around 680,000 in 2023:

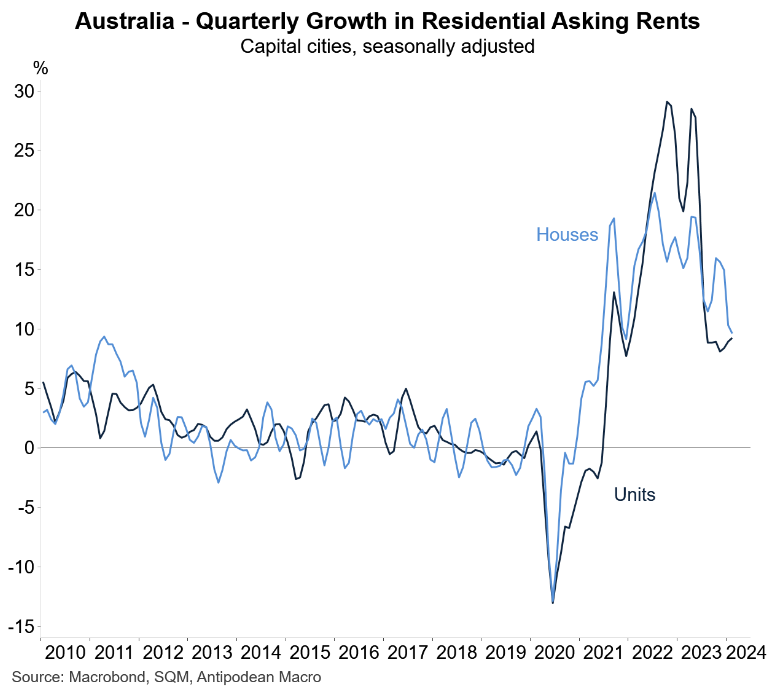

Now look at the next chart on quarterly asking rents. It shows that rents turned negative at the start of the pandemic when immigration collapsed, only to then shoot the lights out when borders reopened and record numbers of migrants poured in:

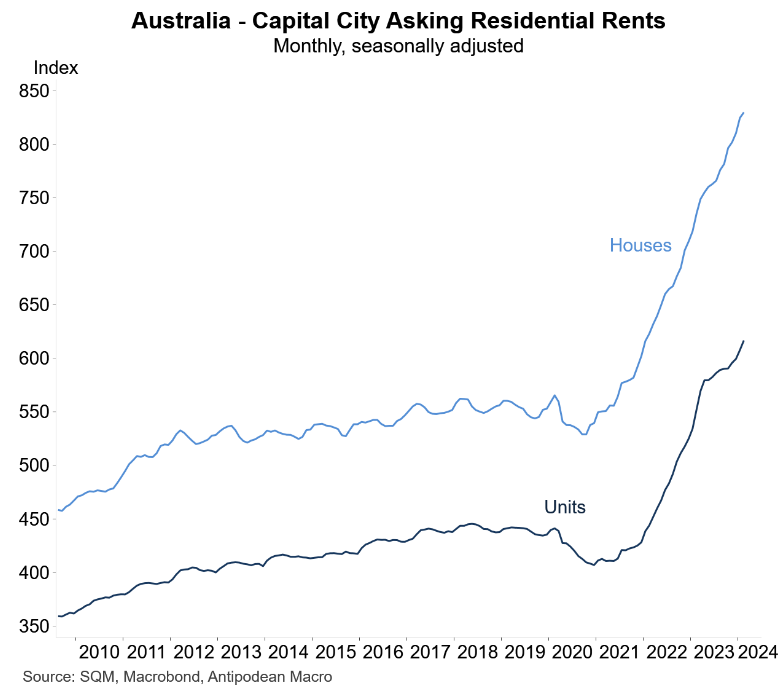

Accordingly, Australia has witnessed an unprecedented surge in rents following the record explosion in immigration:

Much like Greens housing spokesman Max Chandler-Mather, culture warriors like Maiy Azize are standing in the way of affordable rental accommodation by supporting extreme levels of immigration, which crush-load housing, infrastructure, and living standards.

They are useful idiots of business and property elites.