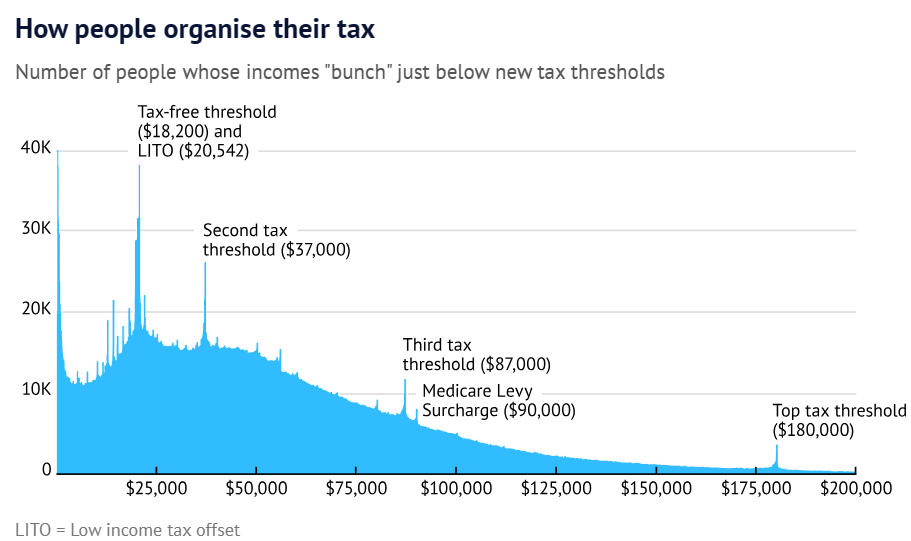

Academics at the Australian National University and the University of Sydney have studied 189 million tax records between 2000 and 2018 and found that there are 50 times more people than expected bunched just below the point at which they would move into a higher tax bracket.

Report co-author, ANU tax specialist Bob Breunig, stated that Australia’s various tax deductions, along with the family tax system, enabled people to change their marginal tax rates.

“It shows there’s a lot of manipulation in the system with trusts being used to move income around. It’s the self-employed and people with trusts doing it”, he said.

“You don’t make $179,999 for five consecutive years without a pay rise”.

Economist Chris Richardson agreed that Australia’s tax system incentivises minimisation strategies.

Even so, the number of Australian workers who are subject to the highest marginal tax rate of 45% has increased sharply over the last 15 years, due to nominal wage inflation.

The tax rate on people earning more than $180,000 a year rises to 47% when the Medicare levy is taken into account.

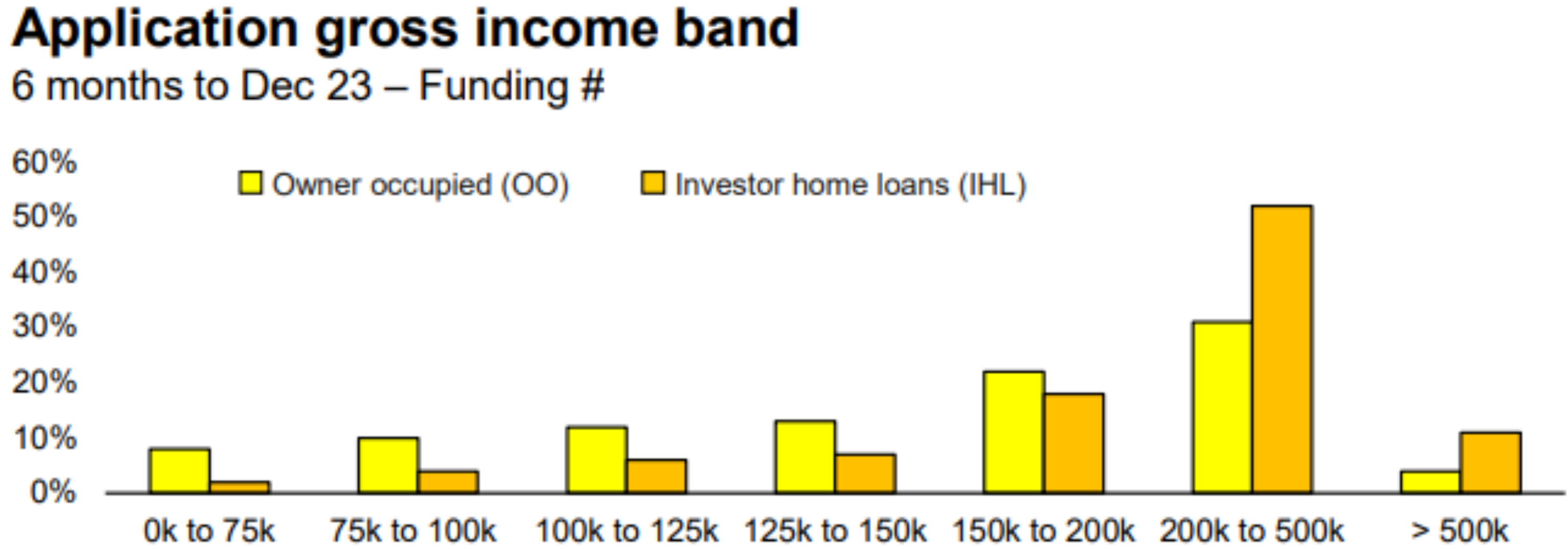

High marginal tax rates also explain why higher income earners have leveraged heavily into investment properties to minimise their taxes via negative gearing:

Source: CBA Investor Presentation

As shown above, households with incomes above $200,000 have leveraged-up massively into investment property, according to CBA data.

This cohort accounted for around 60% of all CBA investor home loans taken out in the 6 months to December 2023.

Stonehouse Financial partner Martin Baker says more of his firm’s clients who pay the highest tax rate are reconsidering whether it is worth working for five days a week, given that they effectively work for four hours on Fridays just to pay their tax.

He warned that the nation’s productivity levels may be negatively impacted by the growing trend for people on high incomes to shift to a four-day working week.

“When clients earn more than $180,000 for the first time, they are often surprised by the amount of tax they have to pay”, Baker said.

“This significant amount of tax makes many clients wonder if it’s worth the extra effort to go to work for eight hours only to work for the government for four hours to pay the tax.

“Some would say this is work-life balance. But I wonder what impact this has on employers who lose their most productive and experienced staff one day every week, and how that impacts Australian productivity.”

Former Treasury economist Robert Carling believes a lower and flatter personal income tax scale would reduce the incentive for tax planning via trusts, negative gearing and small companies subject to the 25%.

“The revenue loss wouldn’t be nearly as great as Treasury claims because of a reduction in tax avoidance, but Treasury doesn’t like to factor in those behavioural responses”, Carling says.

It is hard to disagree. Australia’s tax system has become far too reliant on personal income taxes, while the proportion of taxes coming from indirect sources (e.g., GST and fuel excise) is declining.

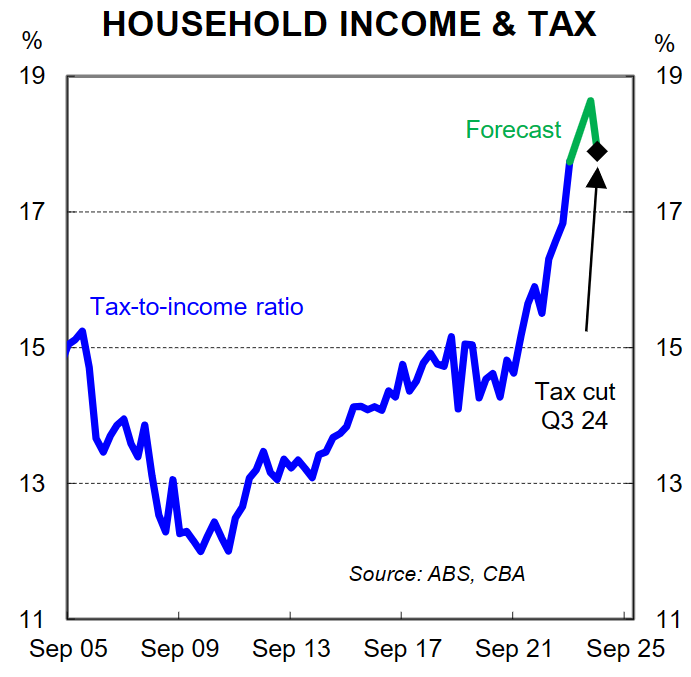

As shown above, the share of household income lost to personal income taxes hit an equal record high of 17.2% in the September quarter of 2023, and will grow higher even after the Stage 3 tax cuts.

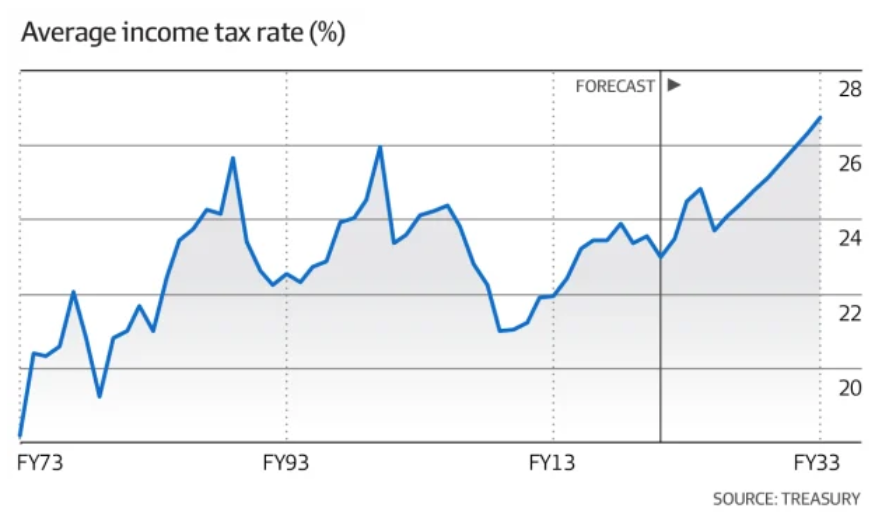

Indeed, the Australian Treasury forecasts that average tax rates will continue to rise courtesy of bracket creep from inflation:

The growing income tax burden will inevitably encourage more use of tax minimisation strategies, alongside negative gearing, to lower tax bills.

It is unsustainable, inefficient, and inequitable for Australia’s tax system to be so heavily reliant on a shrinking number of workers paying income taxes.

This is especially so given that the elderly population is growing in size and paying less tax than ever before, despite holding the majority of the nation’s wealth.

Australia needs proper tax reform that broadens the base away from productive effort (taxing people) and towards more efficient sources such as resources, land, and consumption.

Moving the tax base away from personal income taxes would also minimise the need to import workers through mass immigration to increase the federal budget’s income tax revenue.

The 2010 Henry Tax Review has already laid the blueprint for reform and merely needs updating.

Australia must not let tax reform slide for another decade, punishing workers and productivity in the process.