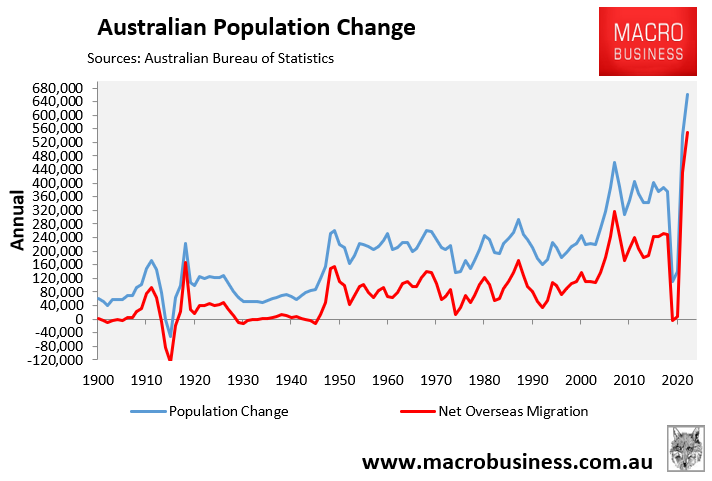

In the year ending September 2023, Australia’s population increased by a record 660,000 people, owing to a record high net overseas migration of 549,000.

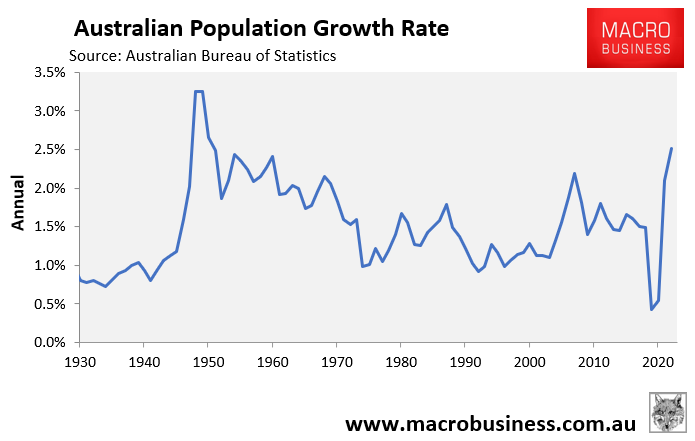

In percentage terms, Australia’s yearly population growth rate of 2.5% was the highest since 1952.

Anyone living in Australia is aware of the implications, with the country dealing with the biggest rental crisis in living memory, as well as declining productivity growth, overburdened infrastructure, and a per capita recession.

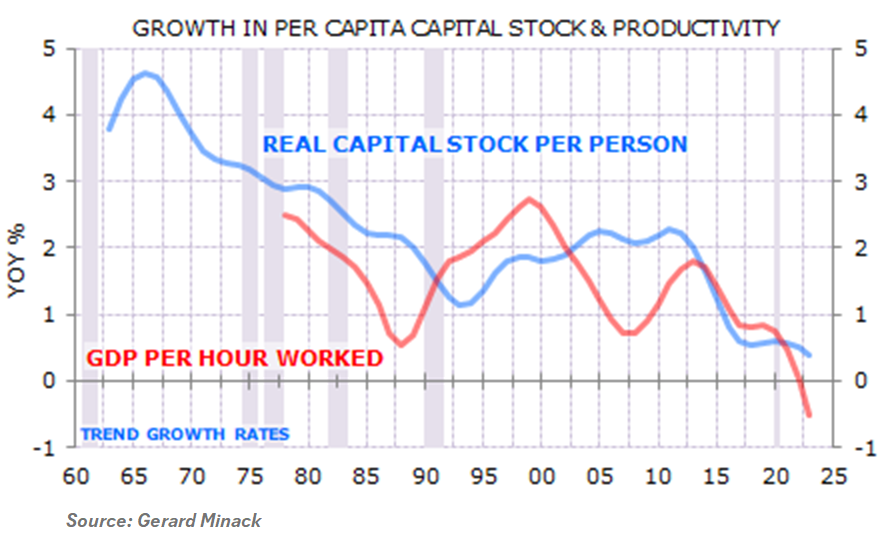

Independent economist Gerard Minack recently explained that Australia’s population boom is a key driver of the nation’s poor productivity through what economists term “capital shallowing”, because business investment, infrastructure, and housing have failed to keep up with population growth:

Source: Gerard Minack

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, Minack wrote in his November report.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, Minack wrote.

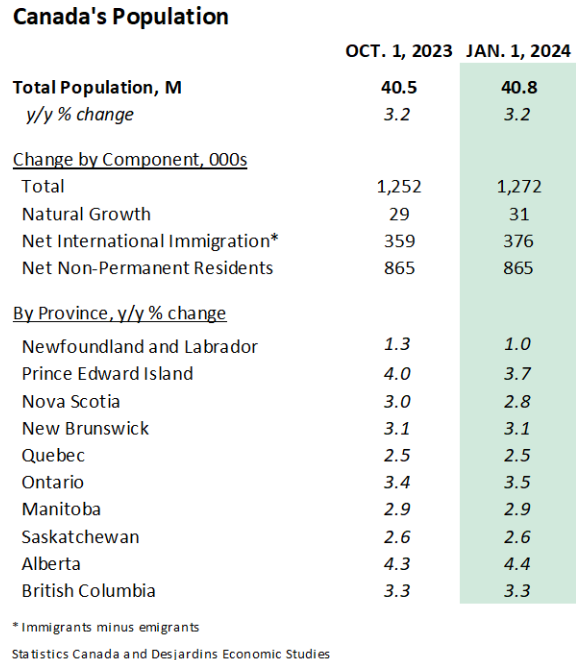

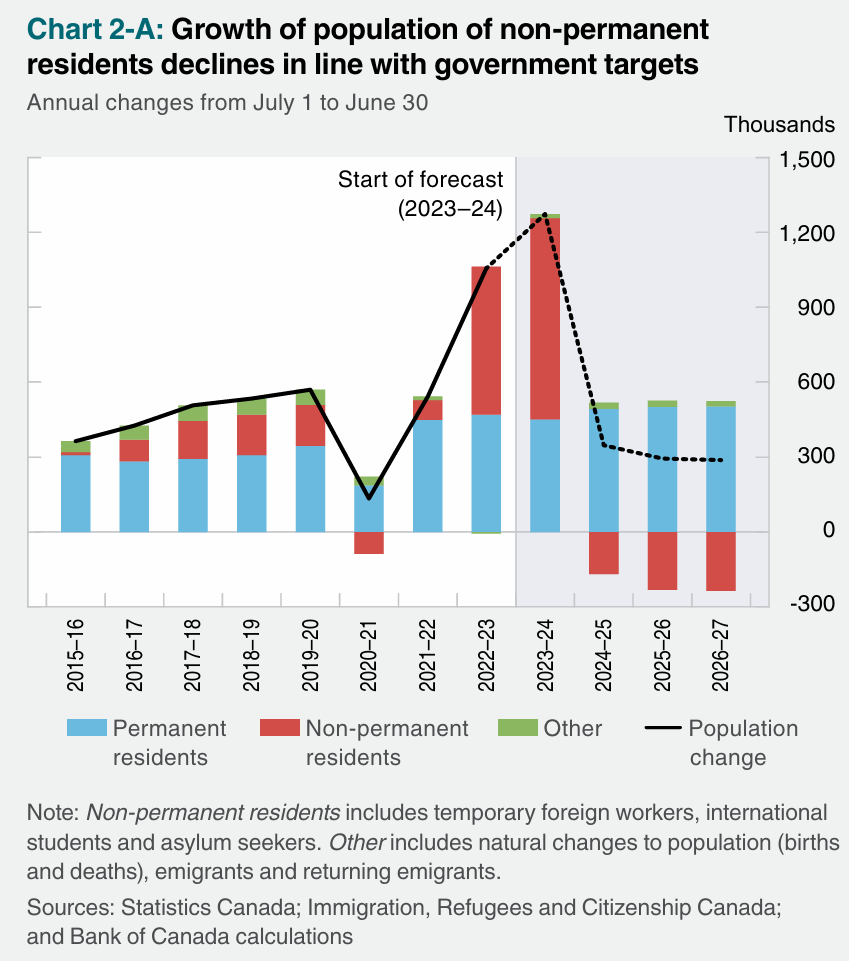

Canada has experienced an even bigger population expansion of 1.27 million (3.2%) in 2023 due to net overseas migration of 1.24 million:

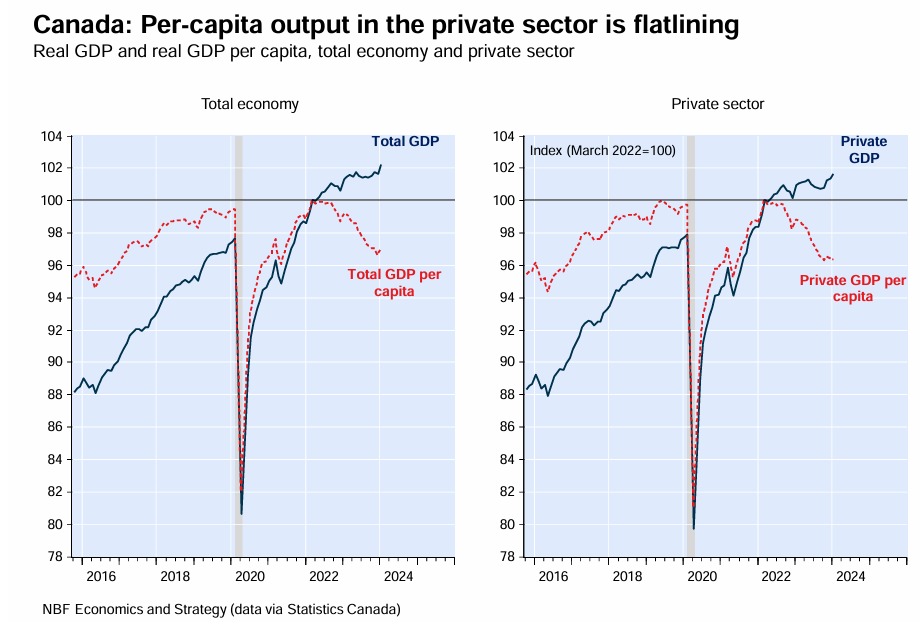

In turn, Canada has experienced an even worse rental crisis and per capita recession than Australia:

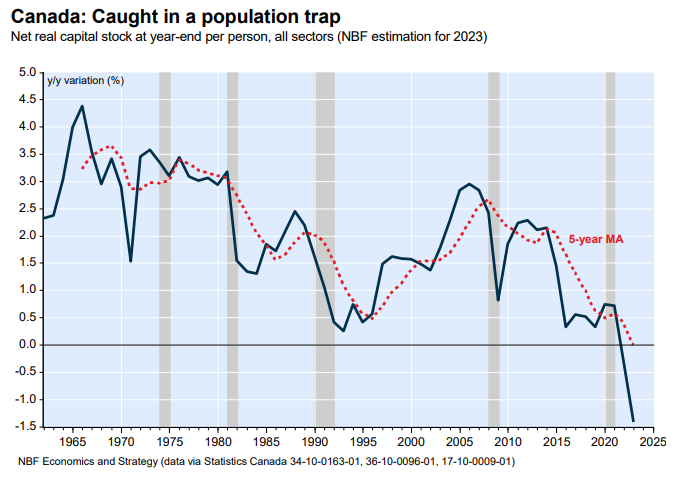

Like Gerard Minack did for Australia, economists at the National Bank of Canada warned that Canada is caught in a population trap of falling productivity because of capital shallowing.

“No increase in living standards is possible, because the population is growing so fast that all available savings are needed to maintain the existing capital-labour ratio”:

“Why is our productivity record so bad? Could it be that our demographic ambitions are too high relative to the stock of capital available in the country? According to our calculations, Canada’s capital stock per capita collapsed close to 1.5% in 2023”.

“This means that our population is growing so fast that we do not have enough savings to stabilize our capital-labour ratio and achieve an increase in GDP per capita”.

“Simply put, Canada is in a population trap for the first time in modern history”…

“Canada is caught in a population trap that has historically been the preserve of emerging economies. We currently lack the infrastructure and capital stock in this country to adequately absorb current population growth and improve our standard of living”.

“Our policymakers should set Canada’s population goals against the constraint of our capital stock, which goes beyond the supply of housing, if we are to improve our productivity”.

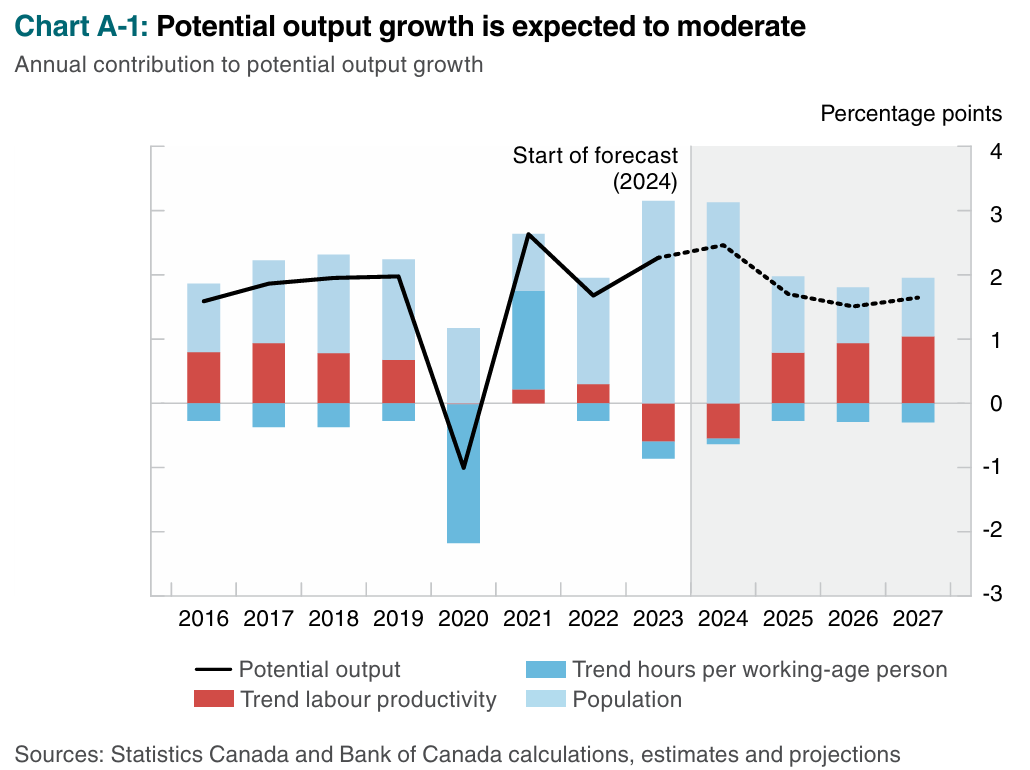

Canada’s central bank, the Bank of Canada, has released its April Monetary Policy Report, which also fingers capital shallowing for the nation’s poor productivity:

“Trend labour productivity (TLP) growth is estimated to have fallen in 2023, pulling potential output growth down by 0.6 percentage points. This weakness in TLP growth is expected to continue in 2024”.

“Large increases in the size of the working-age population as well as modest business investment have led to a decline in the stock of capital per worker in 2023 and 2024”.

Hilariously, the Bank of Canada expects labour productivity growth to rebound on the back of projected sharp falls in immigration levels:

“With population growth expected to normalize in 2025 and beyond, and investment to pick up, trend labour productivity growth is expected to gradually improve”.

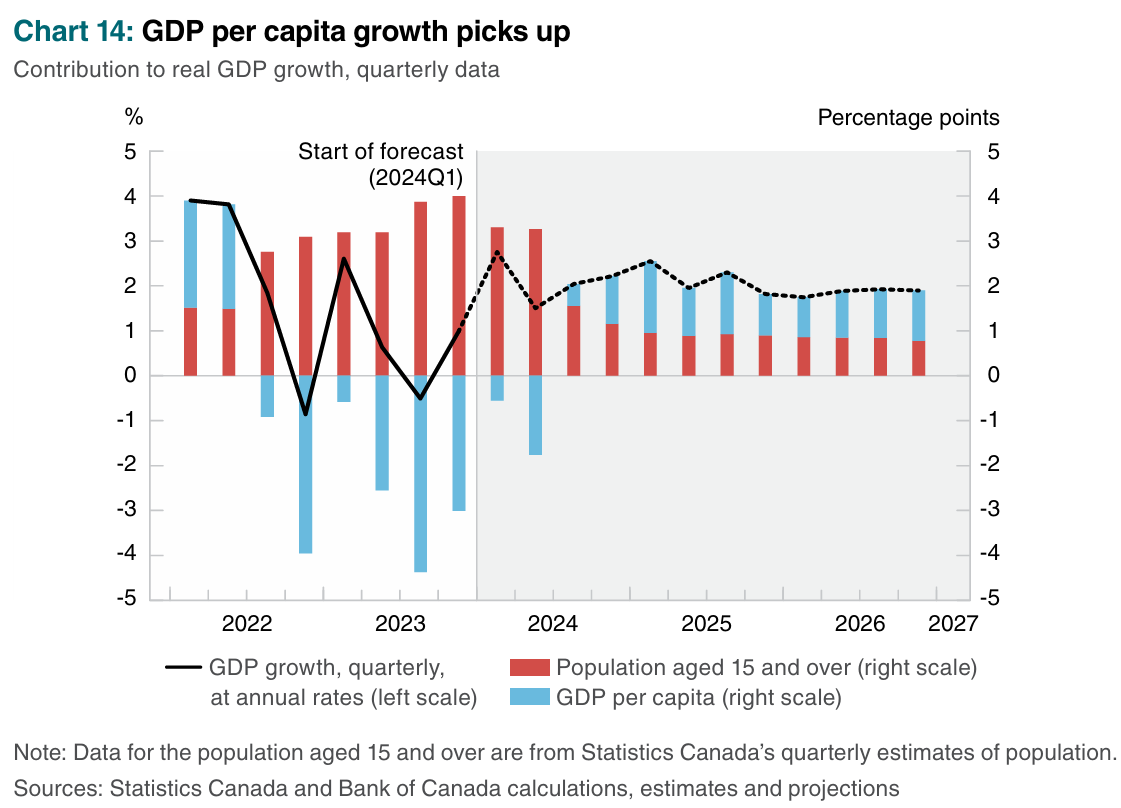

The Bank of Canada also anticipates that per capita growth will rebound as population growth falls:

“A modest pickup in labour productivity growth partially offsets the slowdown in population growth”.

Earlier this month, the former RBA governor Phil Lowe made similar observations about Australia, noting:

“The capital stock is not rising quickly enough to deal with the rapidly rising population”.

“It’s most evident to most Australians in the housing market – where the number of houses and apartments we’re building is not fast enough for the rapid growth in population”.

For resource-rich nations like Australia and Canada, you could not devise a dumber growth model than operating a population Ponzi economy.

Not only does mass immigration dilute your capital base, harming productivity growth, but it also necessarily spreads fixed mineral riches among more people, resulting in lower per capita wealth.