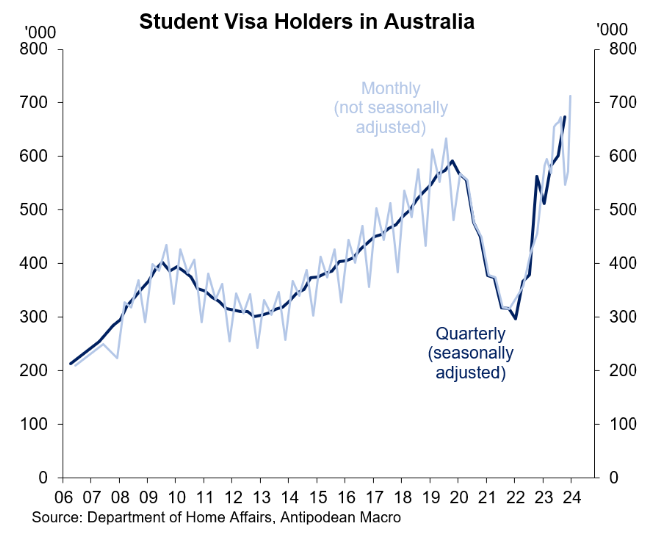

South Asian students are a key driver of Australia’s record increase in net overseas migration.

After the former Coalition Government relaxed the cap on international student work hours and extended the time VET graduates could stay in Australia after completing their degrees, the number of South Asian students arriving for work and residency increased dramatically.

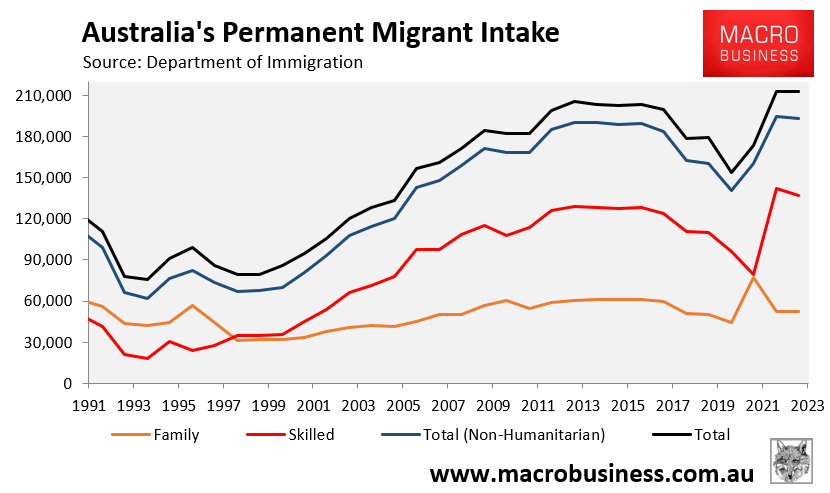

The Albanese government then boosted permanent migrant intake to record levels, improving students’ chances of permanent residency.

Labor also extended the number of hours students can work while studying (to 24 hours a week from 20 hours pre-pandemic).

The government also extended post-study work rights for international university graduates (revoked in February) and negotiated migration accords with India, providing Indians with five-year student visas and eight-year post-study work visas.

These policy changes have encouraged huge volumes of non-authentic students, dubious education agents, and scam ‘ghost colleges’ that have thrived.

According to a recent Navitas poll of study intentions, students from South Asia and Africa select a study location based on their ability to obtain work rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency:

South Asia and Africa care about work and migration, not education quality.

In contrast, students from these two continents are least concerned about educational quality.

Opportunities to work while studying and post-study work rights rank highly for all source countries other than students from China and Europe.

This suggests that Australia’s international education trade would collapse if work rights were significantly curtailed or cancelled since living and working in Australia is their key motivation.

To nobody’s surprise, the Albanese government’s reversal of its decision to extend post-study work rights for international university graduates by two years has angered students, who claim they would have chosen another destination.

“Many international students were unaware of Australia’s recent visa policy changes before they arrived Down Under, and a sizeable proportion would have gone elsewhere had they known, according to a survey”.

“The questionnaire of more than 400 current and prospective students found that only two in five knew that Australia had cancelled its two-year extension to post-study work rights”.

“Over one in four prospective students said the policy shift had changed their minds about going to Australia”.

The survey also showed that nearly seven in ten international students work while studying, with most working in unrelated fields to their study:

“The survey found that 69% of current students were undertaking paid work alongside their studies, but only 23% had jobs that related to their studies”.

“Most said they had been unable to secure relevant employment because they lacked residency or full-time work rights”.

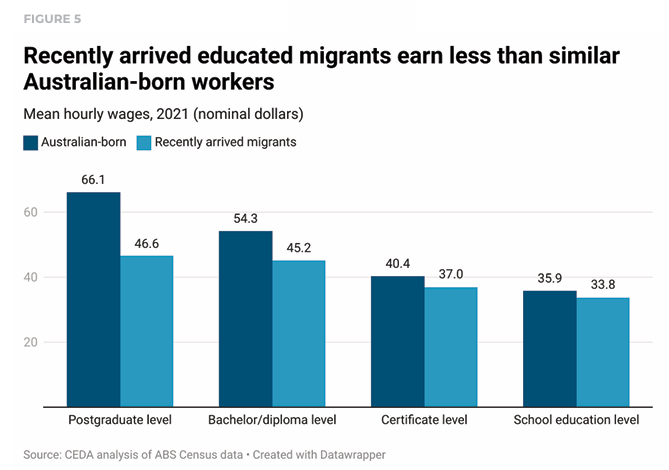

This follows a recent study from the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), which showed that “recent migrants earn significantly less than Australian-born workers” and that “migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”, earning more than 10% less than Australian-born workers on average.

The CEDA report also showed that the unemployment rates of recent skilled migrants are higher than those of Australian-born workers.

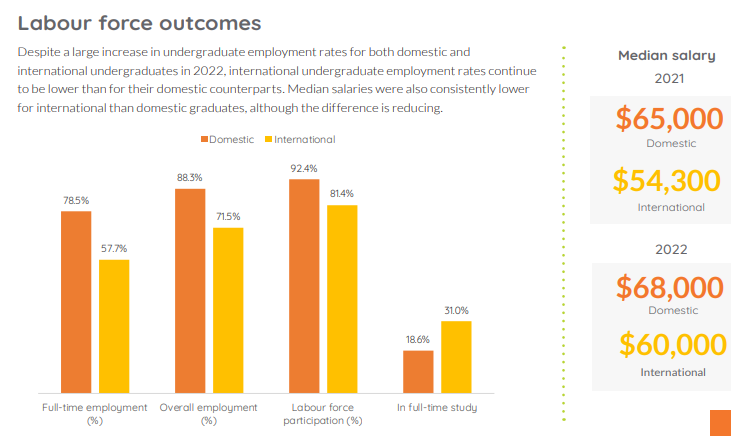

CEDA’s findings are supported by the latest Graduate Outcomes Survey, which shows that international graduate employment rates, participation rates, and median salaries are well below those of domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

Instead of continually lowering standards to attract large numbers of international students of questionable quality, policymakers should concentrate on attracting a smaller pool of exceptional (genuine) students.

This could be done by raising financial barriers to entry, increasing entrance requirements (particularly for English language proficiency), raising pedagogical standards, abolishing group assignments, and severing the clear link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

These reforms would improve student quality, increase export income per student, raise wages and working conditions in low-skilled jobs, and reduce enrolment levels to manageable and sustainable levels, thereby improving local students’ learning environments and relieving population pressure.

In short, international education must prioritise quality over quantity.

Otherwise, Australia will confront a resurgence of the preceding decade’s chronic youth unemployment, wage theft, exploitation, and overcrowding in housing and infrastructure.