Data from the Department of Education shines a bright light on how the composition of Australia’s international student enrolments has changed for the worse.

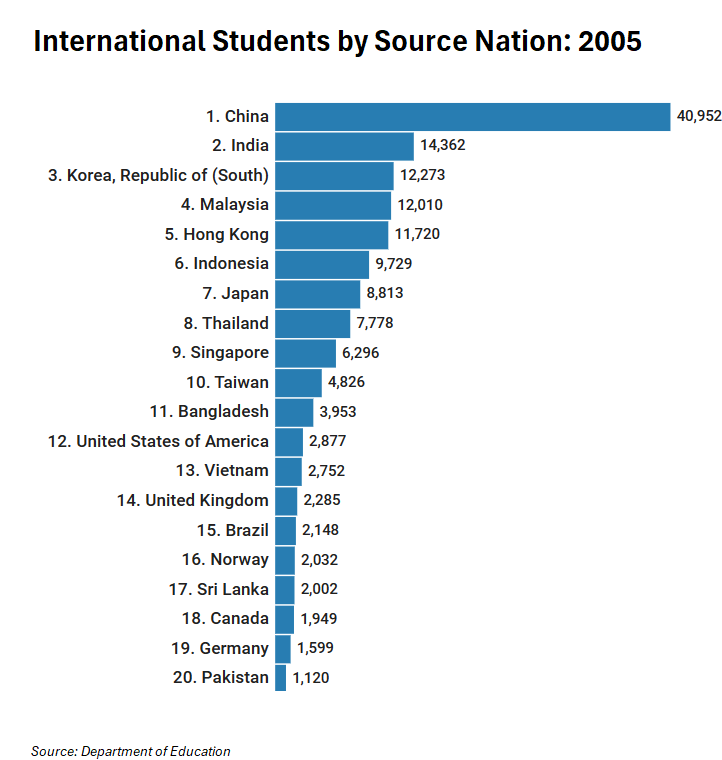

In January 2005, there were a total of 173,787 international students enrolled in Australia.

As illustrated in the following chart, China (40,952) dominated enrolments, with India (14,362) in a distant second place:

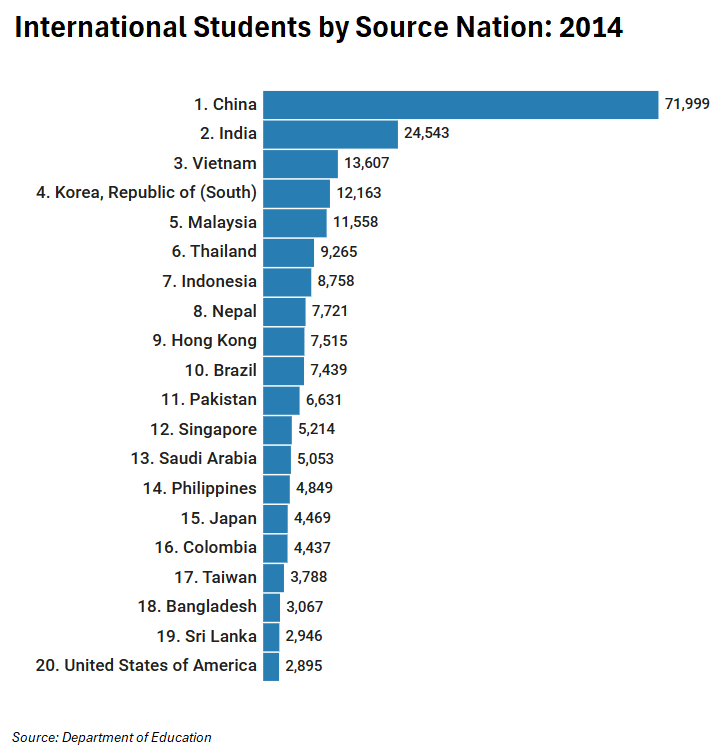

Nine years later, in 2014, Australia’s total international student enrolments had risen to 258,098, with China (71,999) again dominating enrolments and India (24,543) in a distant second place:

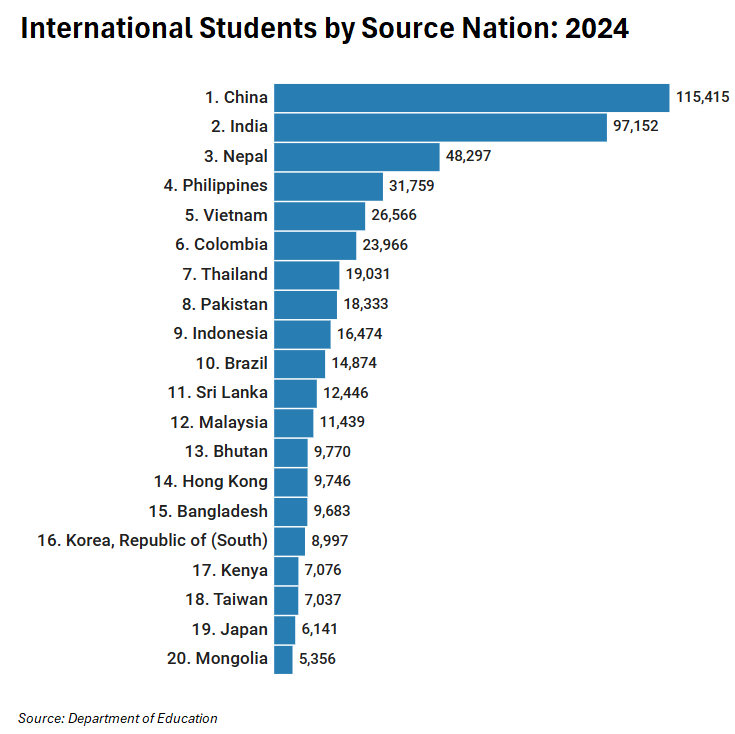

Fast forward a decade to January 2024 and there were 567,505 international students enrolled in Australia.

While China still comprises the most international students (115,415), there has been massive growth in Indian (97,152) and Nepalese (48,297) students:

This shift toward students from South Asia presents quality concerns for Australia’s international education sector.

A recent Navitas survey of study intentions found that students from South Asia and Africa select a study destination based on their ability to obtain work rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency:

South Asia and Africa care about work and migration, not education quality.

In contrast, students from these two continents are least concerned about educational quality.

Opportunities to work while studying and post-study work rights rank highly for all source countries other than students from China and Europe.

To add insult to injury, Australia’s has experienced the fastest growth in student numbers from nations that undertake paid employment in Australia to support themselves, whereas only around one-fifth of Chinese students do so:

Therefore, the notion of international education ‘exports’ only genuinely applies to Chinese students, since they usually fund themselves with Chinese money rather than employment income earned in Australia.

As explained by Associate Professor Salvatore Babones in his recent book, “Australia’s universities, can they reform”:

“In reality, everyone (except perhaps the government and the universities) knew that many international students pay for their courses out of the proceeds of their work in-country, often working excessive hours under exploitative conditions, in violation of their visa terms”.

“This situation is especially common among South Asian students, and is reflected in the steep fall-off in South Asian student numbers when teaching moved online”.

“With prospective students unable to rely on employment income in Australia to support their studies, new commencements of Indian students at Australian higher education providers fell 65% between 2019 and 2021; for Nepali students, the decline was 37%; for Pakistanis, 45%; for Sri Lankans, 54%”.

“These countries are simply too poor to send large cohorts of international students to Australian universities based on family resources alone”.

“For many South Asian students, a student visa is a very expensive but thinly disguised work visa”.

The above explains why international education is primarily a people-importing immigration industry as opposed to a genuine education export industry.

Student visas are mostly low-skilled work visas in disguise.

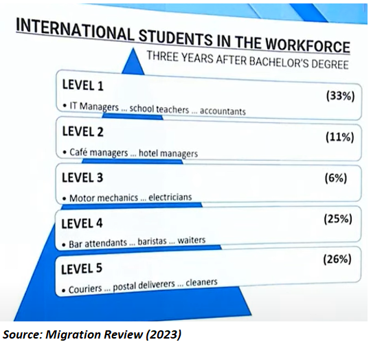

The same applies with post-study international graduates, with the Migration Review finding that 51% of graduates with a bachelor’s degree who had been in Australia for three years were working in low skilled jobs:

If work rights and permanent residency were scaled back, the numbers arriving from these source nations would crash.