Markets love to do a Costanza. But it cannot happen for long when fundamentals are so godawful that they hold sway anyway.

Yesterday, iron ore broke its short squeeze on terrible Chinese data:

Terrible data for iron ore, that is. Overall, the data was fine.

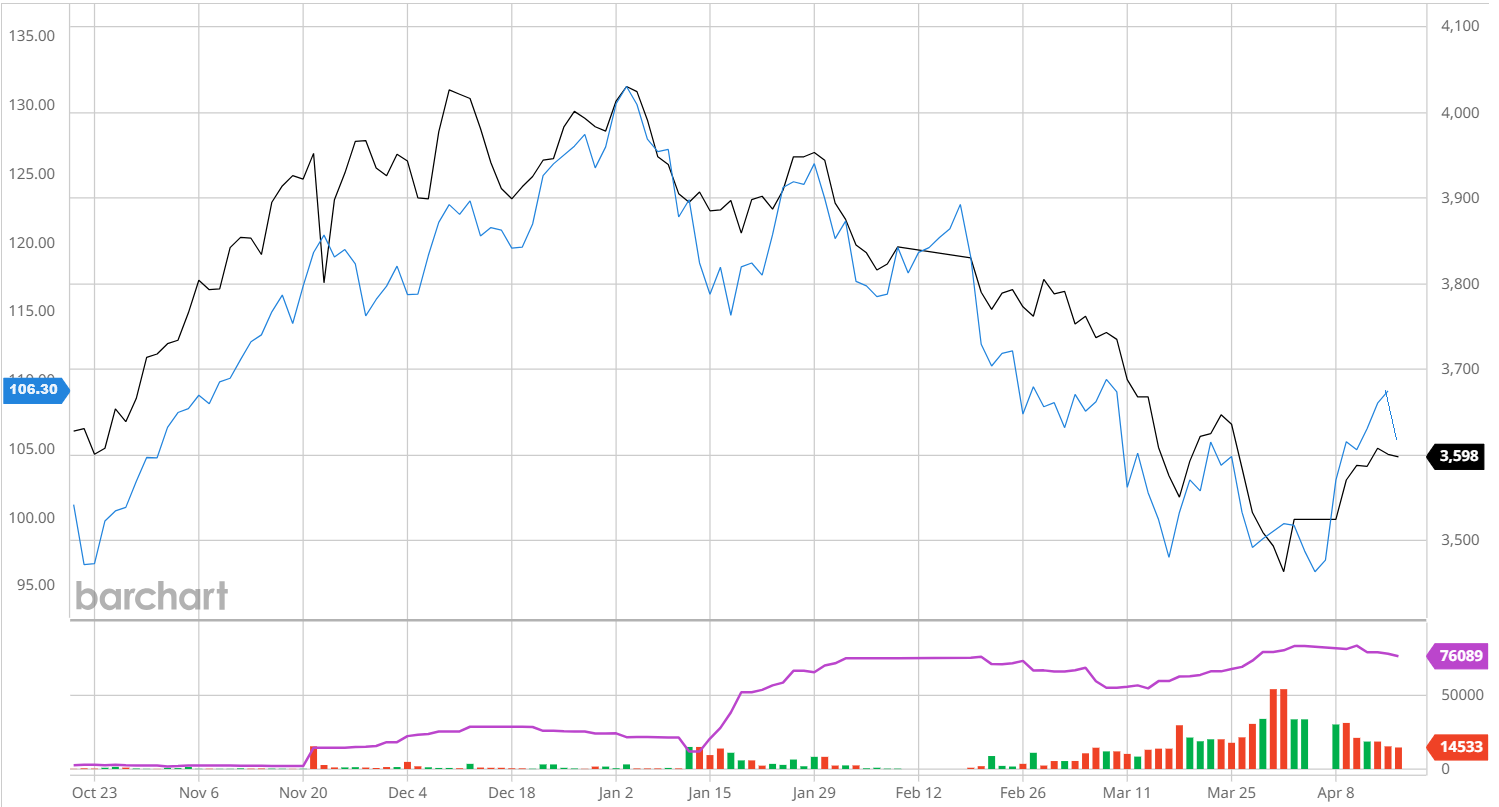

Dalian is as volatile as ever for iron ore snd coking coal:

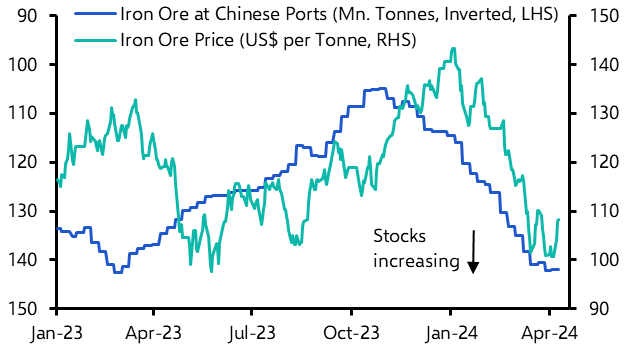

China is accumulating a mighty stockpile of iron ore. Capital Economics:

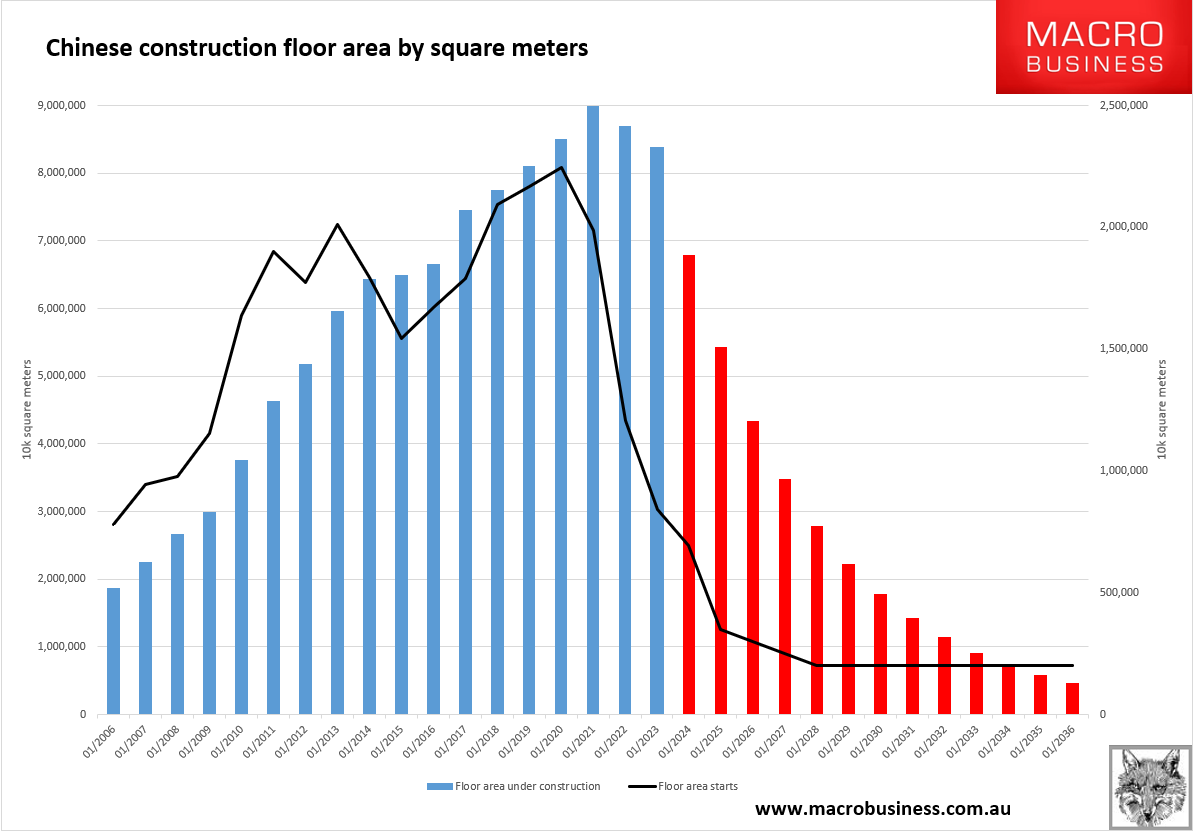

This year’s falls in iron ore prices are likely to have been a dress rehearsal for what’s ahead. Our China team’s forecast for the property sector to halve by the end of the decade does not bode well for iron ore producers’ plans to ramp up production. What’s more, China’s push to control emissions from the steel industry means that iron ore consumption is set to fall even quicker than steel production

At current rates, construction volumes are on track to halve by 2026:

So what’s with the big pile? Clyde Russell:

The question is whether the rise in stockpiles is due to anticipated strong demand, or a function of traders buying too much and being forced to hold inventories.

It’s most likely that demand expectations have been positive, as the rise in inventories has been sustained and constant in the past five months.

Another possible factor is China’s steel mills are trying to build a larger iron ore stockpile in order to give them some flexibility in trimming imports if they deem prices have risen too high, or too quickly.

This method of seeking to influence prices through using stockpiles is something that Chinese oil refiners and traders appear to have adopted in recent months.

It’s an odd one because mills are too fragmented to operate a strategic stockpile but, equally, are far too depressed about the outlook to stockpile for rising demand.

It might just be seasonal.

Either way, because demand is so bad, with pig iron output down 7% in Q1, the great port pile is now a strategic stockpile that can affect prices.

Usually, the more tightly held mill inventories are a better price guide in the short term. They are currently reasonable:

But the port pile does tend to set the longer term price trend.

When it does begin to shrink, I estimate it will be worth about $1 for every tonne of movement, either way.

In the 2015 crash, the pile shrank to 80mt.

Do the math.